How Sandra Day O'Connor Became the First Woman Supreme Court Justice

Evan Thomas has written what should prove to be the seminal biography of Sandra Day O'Connor, a trailblazer who wielded tremendous power on the court as the master of the elusive middle ground.

April 23, 2019 at 01:17 PM

7 minute read

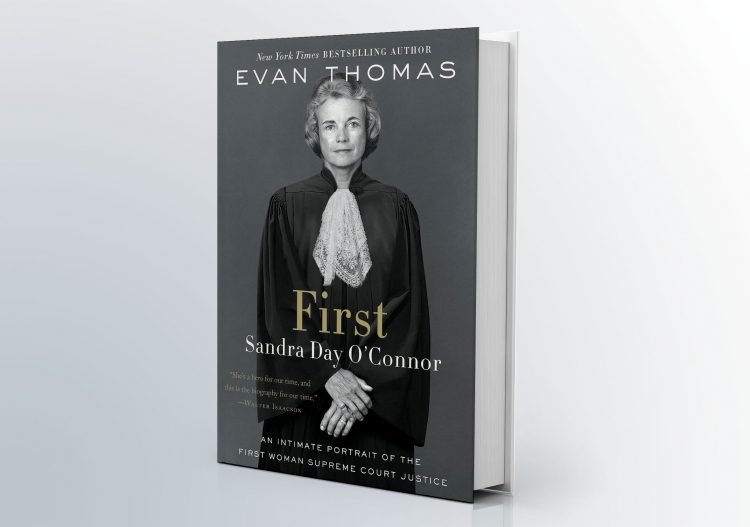

First: Sandra Day O'Connor, An Intimate Portrait of the First Woman Supreme Court Justice

First: Sandra Day O'Connor, An Intimate Portrait of the First Woman Supreme Court Justice

By Evan Thomas

Random House, New York, 496 pages, $32

Perhaps Ronald Reagan's greatest legacy was his 1981 appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor as the first woman justice of the Supreme Court. The choice enraged his base, which doubted her conservative credentials. Over the next 24 years, she constantly frustrated these critics by writing opinions that narrowed close rulings, thereby denying conservative justices the sweeping pronouncements they sought to overrule precedents that liberals held dear. In his new book, Evan Thomas has written what should prove to be the seminal biography of O'Connor, a trailblazer who wielded tremendous power on the court as the master of the elusive middle ground.

The author is a former correspondent and editor of Time and Newsweek who has previously published excellent biographies of Edward Bennett Williams, Robert Kennedy, Richard Nixon, John Paul Jones and Dwight Eisenhower. Granted full access by O'Connor and her family to the former justice's papers, colleagues, law clerks and friends, the author has constructed a compelling narrative that provides a rich and multi-dimensional portrait of one of the most consequential women in American history. Written for a mass readership, lawyers will find the book to be satisfying, particularly the author's deft use of the countless interviews conducted of O'Connor's law clerks and fellow justices on the court.

Born in 1930, O'Connor grew up on a 198,000-acre cattle ranch in Arizona, the Lazy B, which in her youth had no electricity, hot water or telephone. As a “ranch girl,” she was athletic and precocious. Throughout her life, O'Connor would remember that the ranch had taught her about hard work, resourcefulness and competitiveness. “It was no country for sissies,” she recalled.

O'Connor was the eldest of three children born to Ada Mae and Harry Day. Her father was a domineering man who could be “charming, blunt and difficult.” Even though New Deal programs saved his ranch during the Great Depression, he always remained a conservative libertarian who resented the federal government in general and President Franklin Roosevelt in particular.

Ada Mae was a stylish daughter of El Paso. When she married the rancher, her mother took a dim view of the match, warning her “don't ever learn to milk the cow.” As described by the author, Ada Mae was an elegant and well-read woman who “did not allow ranch life to harden her.”

One trait that O'Connor inherited from her father “was the unfortunate need to have the last word.” She became famous for her “bossiness,” a term O'Connor even “used to describe herself.” But as a girl, O'Connor “learned by watching her mother.” She learned how to “not let bullying or passive-aggressive males get under her skin. She learned not to take the bait.” According to the author, that “may have been the most valuable lesson.”

An outstanding student, O'Connor arrived at Stanford as a 16-year-old freshman. She majored in economics. One of the strong parts of the book is the author's description of O'Connor's coming of age, from her active Stanford social life to her intellectual inspirations. Her father, a “strictly pay-as-you-go man,” became curmudgeonly when “she came home spouting the deficit spending theories of John Maynard Keynes.”

A recurring theme throughout the book is how the “purposeful” O'Connor consistently overcame gender stereotypes. She excelled at Stanford Law School and served on the editorial board of the law review, where she dated and received a marriage proposal from classmate William Rehnquist. During her last year of law school, she became engaged to another law review editor, John O'Connor. They married in 1952 and later settled in Phoenix. While her husband landed a job with a prestigious Phoenix law firm, O'Connor partnered with a local lawyer, Thomas Tobin, at a small firm located in a strip mall. In the 1950s, large law firms had no place for women attorneys.

During the early 1960s, O'Connor became active in local G.O.P. politics. The author adroitly describes O'Connor's superb networking skills, which brought her to the attention of Senator Barry Goldwater, who became a mentor. In 1965, she began her public service as an assistant state attorney general.

Between 1969 and 1975, O'Connor made her first significant mark in public life in the Arizona state Senate, becoming in 1973 the first female majority leader of any state Senate. Known as “Old Steely Eyes,” she was a “no-nonsense” legislator who championed the limiting of spending growth and the adoption of a merit selection system for judges. Although O'Connor had experienced sexism throughout her career, she did not support the Equal Rights Amendment. Instead, she worked to change dozens of laws that discriminated against women.

Tired of the legislature, O'Connor moved to the Arizona bench, where she served as a trial court judge (1975-79) and an appellate judge (1979-81). According to the author, “O'Connor was well regarded for the quality of her written opinions and as a fair judge.” But she received low marks from the local bar in the category of “courtesy to lawyers,” which meant that she limited adjournments and showed little patience for unprepared lawyers.

During the 1980 presidential campaign, Reagan promised to put a woman on the Supreme Court. In 1981, Justice Potter Stewart retired. As recounted by the author, O'Connor made the shortlist of four but was considered obscure. The knowledge gap was soon filled, however, by effective lobbying from her Stanford classmate, Justice Rehnquist, Arizona's two U.S. Senators, and Chief Justice Warren Burger, who had previously spent time with her at the Inns of Court.

Although the Senate confirmed O'Connor by a vote of 99-0, the run-up to her confirmation was tumultuous. The author does a credible job of recounting the furor anti-abortion activists raised against her nomination, given her Arizona legislative record, which had included a pair of pro-abortion votes. These activists suspected, correctly as it later turned out, that O'Connor would be unwilling to overturn Roe v. Wade.

Nearly 250 pages of the book are devoted to O'Connor's service on the Supreme Court. The best parts of the book detail her personal relationships with the other justices. Lewis Powell was her closest friend and mentor. Harry Blackmun was petty and resented the attention she received. William Brennan found her challenging because she resisted his lobbying efforts. Antonin Scalia lambasted her in biting dissents, but on a personal level was friendly and gregarious. Rehnquist was at first distant and aloof until he later became chief justice and his wife died.

Regarding O'Connor's jurisprudence, the author highlights the trait that most infuriated conservatives, which was her tendency to decide cases narrowly and avoid broad pronouncements. In so doing, he describes time and again how O'Connor played the role of the deciding vote in close decisions involving campaign finance, affirmative action, abortion rights, the establishment clause, intrusive group searches and gerrymandering. This narrative is enriched by dozens of anecdotes from her law clerks, who engaged in spirited debates on how the justice should rule.

Beginning in the 1990s, O'Connor's husband began suffering from dementia. The book chronicles her determination to care for him as his disease progressed. In 2005, she decided to retire from the court, because his care had become a full-time undertaking. In so doing, she reasoned that in 1981 he had given up his lucrative legal career in Phoenix to support her in Washington. Now, it was time for her to return the favor.

Jeffrey M. Winn is an attorney with the Chubb Group, a global insurer, and the secretary to and a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Public Is Best Served by an Ethics Commission That Is Not Dominated by the People It Oversees

4 minute read

The Crisis of Incarcerated Transgender People: A Call to Action for the Judiciary, Prosecutors, and Defense Counsel

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Gunderson Dettmer Opens Atlanta Office With 3 Partners From Morris Manning

- 2Decision of the Day: Court Holds Accident with Post Driver Was 'Bizarre Occurrence,' Dismisses Action Brought Under Labor Law §240

- 3Judge Recommends Disbarment for Attorney Who Plotted to Hack Judge's Email, Phone

- 4Two Wilkinson Stekloff Associates Among Victims of DC Plane Crash

- 5Two More Victims Alleged in New Sean Combs Sex Trafficking Indictment

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250