'Lamps Plus' Undermines Contract Principles

The decision in Lamps Plus opens the floodgates for creep in two directions and thereby threatens future courts' ability to apply contract law that suits the contract type and context of consent.

April 29, 2019 at 04:43 PM

5 minute read

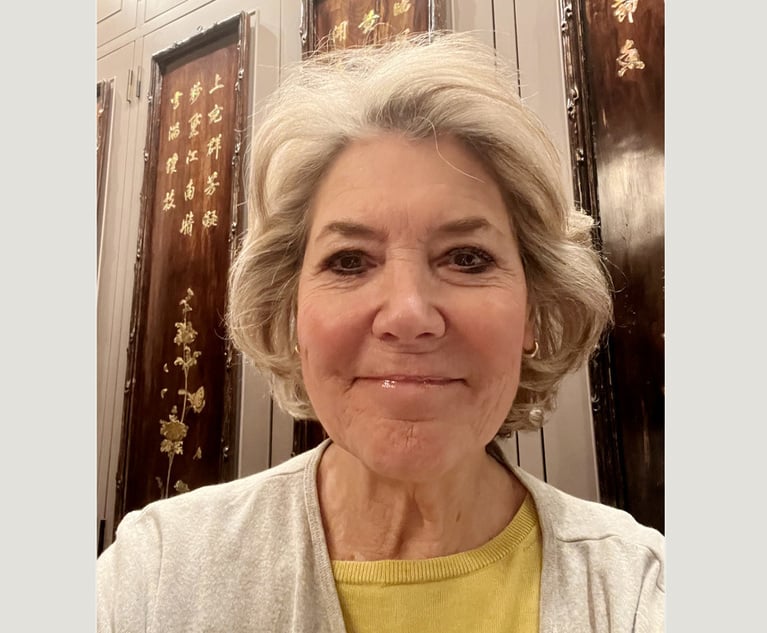

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg speaks at New York Law School on Feb. 6. Photo: Carmen Natale/ALM.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg speaks at New York Law School on Feb. 6. Photo: Carmen Natale/ALM.

In her withering dissent from the Supreme Court's holding in Lamps Plus Inc. v Varela, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg began her opinion by underscoring “how treacherously the court has strayed” in this decision. And the damage to contract principles is greater than the treachery to the goals of the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). Even more fundamentally than the fact that, as Justice Ginsburg noted, the FAA was enacted “to enable merchants of roughly equal bargaining power to enter into binding agreements to arbitrate commercial disputes,” the FAA was intended to make sure state law does discriminate against or disfavor arbitration agreements, as Justice Elena Kagan articulated in her dissenting opinion. The court disregarded this by sidelining the general contract law principle of contra proferentem—construing an ambiguity against the drafter—which does not disfavor arbitration afoul of the FAA, to favor a view of arbitration that discriminates against its class-wide pursuit. In doing so, the court further undermines the project of differentiating between types of contracts and muddies the doctrinal distinctions and rationales that underpin this important project.

In reaching its decision, the Supreme Court continued its worrying trend of expanding the reach of arbitration provisions to preclude consumers and employees from holding companies accountable for negligence and other harms through the law. It also upended basic principles in contract law—not least the meaning of consent. The court's majority ruled that an ambiguously drafted employment agreement barred workers from class-wide arbitration of a claim against their employer for compromising their personal data. As a result, each employee must arbitrate his or her claim individually against the company after it disclosed workers' tax information in a phishing scam.

Scholars and courts have long recognized that context matters in determining the meaning of a contract. As my co-author Ethan Leib and I explore in our article Contract Creep, forthcoming in the Georgetown Law Journal, legal thinkers and judges widely accept that the law should treat non-negotiable fine print contracts imposed by powerful entities on individuals differently than deals struck between sophisticated actors who can fully understand and negotiate terms. As demonstrated in Lamps Plus, individual employees who face a choice between not taking a job or signing the fine print presented to them by their potential employer do not “consent” in the same way as companies do when they negotiate agreements. As our study shows, it is not always easy for courts to differentiate between types of contracts, as doctrine can “creep” between contract types so that courts apply doctrine designed for one context to another type of contract where it threatens to undermine the goals of the law and can blur the underlying rationales. The ruling in Lamps Plus exacerbates this fundamental problem.

Lamps Plus grew out of a claim brought by employee Frank Varela against the company for negligent handling of his private information and invasion of privacy, among other things, when his personal data was hacked from the company database and used to file a fraudulent tax return in his name. As a condition of his hiring, Mr. Varela signed an agreement requiring arbitration “in lieu of any and all lawsuits or other civil legal proceedings relating to” his work at the company, as did about 1,300 other Lamps Plus employees impacted by the scam. The fine print that the company forced employees to agree to contained sweeping language authorizing arbitration but did not specify if it had to be on an individual basis or as a class action. In light of this ambiguity, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the long-standing principle of reading an ambiguous document in favor of the non-drafting party applies with “particular force” to a take-it-or-leave-it contract such as this one.

Given the limitations on employees' ability to control terms to which they “consent,” the Court of Appeals rightly recognized the relevance of the circumstances of a non-negotiable employment contract to construe the agreement. Yet, remarkably if not unexpectedly, the majority opinion of the Supreme Court focused on the “consent” of the company. In fact, Chief Justice Roberts emphasized that “[c]onsent is essential” under the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). The company, that is, could not be compelled to engage in class-wide arbitration. The decision upends the meaning of consent in context and puts a finger on the scale of power. This decision chips away at the ability of employees to take es collective action, action that could be necessary to make the process economically feasible for individuals—and arguably undermined the efficiency goals of the FAA.

The decision in Lamps Plus opens the floodgates for creep in two directions and thereby threatens future courts' ability to apply contract law that suits the contract type and context of consent. It reinforces the trend of treating arbitration provisions—originally recognized as a tool for sophisticated parties—as a matter of general contract law in which the employer-drafter's consent is paramount. And it framescontra proferentem as a public policy doctrine beyond the issue of consent in precisely the context in which its pro-consumer rationale is most compelling—in the context of a fine print form agreement drafted by a powerful repeat player imposed on an employee as a condition of employment. In doing so, the court not only sells out the meaning of the FAA but contributes to undermining an even broader project in contract law. It invites a tide of rules intended to govern one kind of transaction to flood the doctrine developed for contracts in distinctly different contexts. In doing so, it demonstrates the dangers of a generalizing trend in the law for all who see the wisdom in developing contract law that recognizes the ways people can “consent” to agreements, or not, as the case may be.

Tal Kastner is acting assistant professor at NYU School of Law.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Attorney Responds to Outten & Golden Managing Partner's Letter on Dropped Client

3 minute read

Letter to the Editor: Law Journal Used Misleading Photo for Article on Election Observers

1 minute read

NYC's Administrative Court's to Publish Some Rulings in the New York Law Journal Is Welcomed. But It Should Go Further

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1We the People?

- 2New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 3No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 4Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 5Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250