Internet Is an Essential Conduit to Exercising Our Right to Assemble

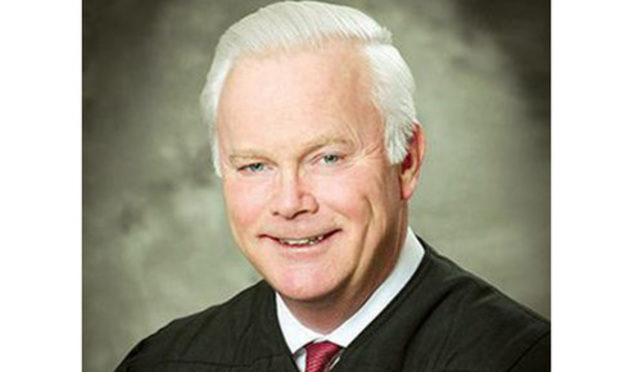

Gerald J. Whalen, Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department

April 30, 2019 at 03:10 PM

5 minute read

Gerald J. Whalen

Gerald J. Whalen

Among the essential rights guaranteed by the First Amendment, “the right of the people peaceably to assemble” seems to garner little distinct discussion, although it is recognized as being inextricably bound with and “equally fundamental” as those of free speech and free press. De Jonge v. State of Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 364 (1937). Indeed, at least one scholar describes this right as having become “a historical footnote in American political theory and law.” See John D. Inazu, The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly, 84 Tul. L. Rev. 565, 566 (2010). Nonetheless, the right to peaceably assemble for the purpose of advancing beliefs and ideas or “to petition the Government for a redress of grievances” (U.S. Const. amend. I) constitutes an “attribute of national citizenship” (United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 547 (1875)).

The importance of the right to peaceably assemble can be found in the traditional characteristics ascribed to its exercise: Often the right is invoked by those who “dissent from the majority and consensus standards endorsed by government” and who seek public, advocacy-oriented visibility (see Inazu, 84 Tul. L. Rev. at 570). The exercise itself tends to be more expressive than simple association, which can be private, and may manifest in parades, demonstrations, and other creative forms of engagement (id.; cf. NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449, 460-62 (1958)).The historical significance of this right, early manifestations of which include eighteenth century political societies and their initially scandalous expressions of open criticism of the federal government, is the “understanding of popular sovereignty and representation in which the role of the citizen was not limited to periodic voting, but instead entailed active and constant engagement in political life” (Robert M. Chesney, Democratic-Republican Societies, Subversion, and the Limits of Legitimate Political Dissent in the Early Republic, 82 NC L. Rev. 1525, 1537-40 (2004); see Inazu, 84 Tul. L. Rev. at 577-81).

Today, assembly is not only a conduit for the expression of political dissent against the government, but an important tool for recognizing and amplifying otherwise marginalized voices in our society. More and more often our nation's citizens meet in cyberspace to opine and discuss and decry and, yes, 'like' positions on issues, not only of politics, but of our societal values as well. This digitalization of the town square bridges physical distances and introduces people, thoughts, and experiences to which we would not otherwise be exposed, and can facilitate understanding and empathy due to the context this communication provides. The Internet permits private interaction, certainly, but it also permits people, regardless of physical distance or other traditional impairments to collective action, to unite to discuss and advocate their shared ideals to the government or the public in general.

Moreover, although the Internet may not be a public forum in and of itself (see generally United States v. American Library Assn, 539 U.S. 194, 205-07 (2003) (plurality opinion); Elizabeth Henslee, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Public Forum, 43 Cap. U. L. Rev. 777, 826-30 (2015)), social media is often the catalyst for the traditional, real-world exercise of the right of assembly in its most “pristine and classic form”: a peaceable gathering to protest grievances inflicted by government (Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229, 235 (1963); Inazu, 84 Tul. L. Rev. at 566). In other words, it has become an essential conduit to the exercise of this right. Far from an idle information stream, activists—seasoned or newly fervent alike—utilize social media to raise awareness, to organize, and to mobilize in person locally, nationally, and globally. What begins as an online thought becomes hundreds of thousands assembling to petition shared grievances against the government—such as the Women's March on Washington and its simultaneous satellite marches throughout the nation. This grass roots method of political and social engagement is far from new. We have simply replaced a bullhorn with a hashtag and a physical flyer with a digital post.

This is not to say that online assembly does not have its dangers. The practical reality of the Internet is that it can divide, rather than unite, when users interact in only self-created echo chambers that parrot their existent views back to them. The constant flow of new information, colored by a poster's own perception or outright disinformation, can undermine attempts at reasoned deliberation and allow debate to devolve into meaningless adherence to a party line. This potential for people to divide into factions, however, is neither new nor a result of technology. The Founders in fact anticipated both this result and the problems arising from this division. “A zeal for different opinions … ; an attachment to different leaders … ; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good.” James Madison, Federalist No. 10. The fix, of course, is not to inhibit the dissenting or differing viewpoints that create factions within our society, inasmuch as this erosion of liberty would “be worse than the disease.” Id. Instead, an essential element of our republican government is the need to ensure that the voice of the majority does not silence the rights of the minority. James Madison, Federalist No. 51. Through the exercise of the right to assembly, now supported by our increased ability to connect and understand, the voices of the marginalized and disenfranchised are amplified, and our nation is stronger for it.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250