Admirers and Adversaries Recall the '24/7' DA Richard Brown

His tenure began in 1991, amid a record crime wave, and ended May 4, leaving behind a legacy intertwined forever with New York City becoming the safest big city in America.

May 06, 2019 at 05:51 PM

7 minute read

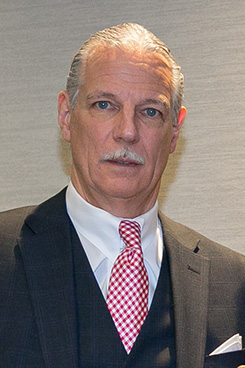

Queens District Attorney Richard Brown in his office in 2017. (Photo: Bebeto Matthews/AP)

Queens District Attorney Richard Brown in his office in 2017. (Photo: Bebeto Matthews/AP)

Richard Brown's recent passing brought to a close his nearly three-decade career as district attorney in Queens—a remarkable tenure that coincided with a dramatic shift in crime that today places New York City among the safest big cities in the United States.

For many, the former appellate judge's 28 years at the helm represent a remarkable success, given the level of relative safety and security communities throughout Queens and across the city enjoy today. For others, Brown's long hold on the office came with a rigidity that failed to change with the times, making Queens a holdout to reforms. Either way, the unparalleled changes the city has faced since Brown was first appointed in 1991 will remain inseparable from his ultimate legacy.

“Dick was 24/7 as district attorney,” Herrick Feinstein partner Scott Mollen told the New York Law Journal.

Scott Mollen

Scott MollenMollen said his relationship with Brown and his family was multigenerational, and vice versa. His prior firm represented members of Brown's family, including his father. Brown served as an associate justice on the Appellate Division, Second Department while Mollen's father, Milton Mollen, was presiding justice.

Scott Mollen said one area that may be overlooked in Brown's history was his time on the bench, both in terms of the impact he had as a judge and how it helped inform his efforts as district attorney.

“I know that, during my father's service as presiding justice, he valued very highly Richard's input and ideas,” he said. “I think that on the court, he helped in general by serving on committees related to the court system, and in essence, acted as a representative of the appellate division in a role that was supporting of my father's work.”

When the opportunity arose for the appointment of a new Queens district attorney following the resignation of John Santucci, Mollen said Brown believed he could bring to bear on the position his experience as an attorney, appellate judge and counsel to Gov. Hugh Carey.

“Richard always wanted to accomplish things that improved the way government operated,” Mollen said. “Being district attorney allowed him to be not merely an adviser, but to be the person making many decisions.”

As an adviser to Brown's first campaign for DA in 1993, Mollen said he watched Brown make an immediate and initial but lasting impact by professionalizing the office, moving it away from a patronage institution and more toward the standards of professionalism set by Manhattan's long-serving district attorney, Robert Morgenthau.

“He was extremely focused on hiring excellent students coming out of law school, and other experienced people. He understood that the responsibility of the office required that he hire the best and brightest that he could find,” Mollen said. “He didn't know how to operate a third-rate office. He would do everything in his power to make sure the office was a first-rate office.”

Robert Masters

Robert MastersExecutive Assistant District Attorney Robert Masters joined the Queens DA's office the year prior to Brown taking over. He, too, saw one of Brown's lasting legacies as the professional evolution into “one of the finest prosecutors offices in the country.”

“He really personified what I think is the distinction that can frequently be lost, between being an elected official and a politician,” Masters said.

Brown believed he owed his constituents the truth, “not what they wanted or hoped to hear at a particular time, but the truth,” Masters recalled.

As an office, Masters said Brown created policies 20 years ago that today continue to be seen as innovations. He pointed to mentorship programs in community schools, the creation of drug courts to combat abuse years ago, and the Queens Court Academy as just a few of the way Brown advanced the office over the years, so often with an incremental approach to ensure “things can be done better.”

“The reality is that others are going to hold his office in the future. I don't know that anyone's ever going to replace him,” Masters said.

As news of his passing circulated, statements of praise and mourning were issued. Among them was state Attorney General Letitia James, who called Brown “a dedicated public servant who was deeply devoted to the people of Queens,” and New York State Bar Association president Michael Miller, who offered praise for Brown “devoting nearly 50 years of his extraordinary career to the pursuit of justice as a highly respected jurist and prosecutor.”

“Today our city mourns a dedicated public servant.” Mayor Bill de Blasio tweeted out from his government account over the weekend. “As the longest-serving DA in Queens history, Richard Brown was committed to making this city safer and brought hundreds of men and women into law enforcement.”

Even before his passing, Brown's long battle with Parkinson's disease required changes that impacted the office going forward. In January Brown said he would not seek reelection. Then, in March, he announced his plan to resign in June.

Kate Levine

Kate LevineThe imminent changing of the guard has created a new fount of criticism and critique about the Queens district attorney's practices, specifically from those seeking to replace Brown. These joined an already vocal group of defense attorneys, legal observers and activists who have effectively pushed for substantial criminal justice reforms in recent years—and who saw the Queens District Attorney's Office as an impediment at times.

St. John's School of Law professor Kate Levine saw the shifts occurring around how the office has operated as a reaction to “a sort of old-guard, law-and-order retrenchment and regressive view on what should and shouldn't be prosecuted.”

Whereas more recently elected district attorneys in the city have been eager to spearhead initiatives around marijuana prosecutions, conviction review units and other progressive criminal justice reforms, the Queens office, under Brown, has been resistant to change.

“It's that trope of this sort of older white male prosecutor not reforming the office as quickly as some of us might hope,” Levine said.

Still, even some of those who've been most consistently on the opposite side of issues with the DA's office spoke of their respect for him.

Tim Rountree, The Legal Aid Society's attorney-in-charge of the criminal defense practice in Queens, said it was “no secret” the defense bar and prosecutors in the District Attorney's Office weren't going to “see eye-to-eye” on any number of issues. But, he added, “it doesn't mean you don't have mutual respect” for one another.

“You're not always going to agree, but you can agree to disagree, and you do the best work as you can possibly do for the people of Queens County,” Rountree said, noting his “tremendous respect for” Brown's work as a public servant.

He pointed to the collaborative work done by the Queens District Attorney's office with the defense bar and other community stakeholders in the creation of the drug courts and other early alternatives to incarceration programs as a “long-standing and tested legacy” of Brown's time as district attorney.

“Overall, he had the citizens of Queens' in his best interests, and he wanted to do the right thing,” Rountree said. “Now, it's time to turn our attention to the future.”

Funeral services for Brown are set to be held at The Reform Temple of Forest Hills on Tuesday, following a procession from the Queens courthouse beginning at 10 a.m.

Related:

Long-Serving Queens DA Richard Brown Dies at 86

John Ryan, Who Will Serve as Acting DA in Queens, Pledges to 'Keep Doing Justice'

Queens Democratic DA Candidates Take the Stage at CUNY Law School

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Orrick Hires Longtime Weil Partner as New Head of Antitrust Litigation

Ephemeral Messaging Going Into 2025:The Messages May Vanish But Not The Preservation Obligations

5 minute read

SEC Official Hints at More Restraint With Industry Bars, Less With Wells Meetings

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Two More Victims Alleged in New Sean Combs Sex Trafficking Indictment

- 2Jackson Lewis Leaders Discuss Firms Innovator Efforts, From Prompt-a-Thons to Gen AI Pilots

- 3Trump's DOJ Files Lawsuit Seeking to Block $14B Tech Merger

- 4'No Retributive Actions,' Kash Patel Pledges if Confirmed to FBI

- 5Justice Department Sues to Block $14 Billion Juniper Buyout by Hewlett Packard Enterprise

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250