Political Battles for an Apolitical Branch

Michael Bobelian's Battle for the Marble Palace reminds us that the judicial appointment war did not begin with Bork but started at least 20 years earlier, with the appointment by President Lyndon Johnson of Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as chief justice.

May 15, 2019 at 10:22 AM

10 minute read

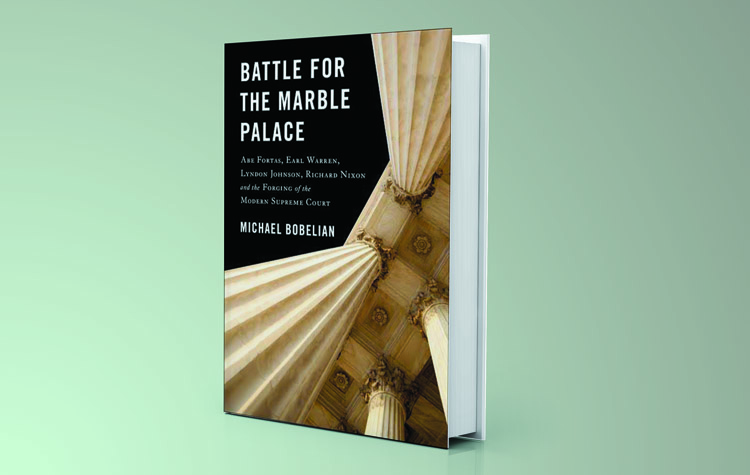

The Battle for the Marble Palace: Abe Fortas, Earl Warren, Lyndon Johnson, and the Forging of the Modern Supreme Court

The Battle for the Marble Palace: Abe Fortas, Earl Warren, Lyndon Johnson, and the Forging of the Modern Supreme Court

by Michael Bobelian (Shaffner Press 2019), 344 pp. Price: $31.99.

Whatever they thought of the judicial merits and qualifications of Merrick Garland and Brett Kavanaugh, many observers were dismayed to see partisan battles fought over appointments to the Supreme Court, the one institution of American government that is supposed to be above politics. There was nostalgia for the days when the appointment process was more dignified—the President nominated a prominent lawyer or official, and the Senate acquiesced. Sixty-two of 70 Supreme Court nominees in the 20th century were approved, most within only a few days of being nominated, and usually by large majorities. See Barry J. McMillion and Denis Steven Rutkus, Supreme Court Nominations, 1789-2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President (Congressional Research Service) (July 6, 2018). Many people pointed to the appointment of Robert Bork, in 1987, as the watershed that turned the appointment process from an orderly coronation to a bare-knuckled brawl.

Michael Bobelian's Battle for the Marble Palace reminds us that the judicial appointment war did not begin with Bork but started at least 20 years earlier, with the appointment by President Lyndon Johnson of Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed Earl Warren as chief justice. That fight, Bobelian explains, was a precursor to the Bork, Garland and Kavanaugh fights to come. Each was a product of a clash of cultures and a deep distrust of what was seen to be an autocratic Supreme Court.

Fortas had been a prominent lawyer in Washington, known for his brilliance and his influence. After a career in government and in academia, he founded his own firm, Arnold, Porter & Fortas, which became one of the preeminent firms in the nation. He represented the rich and powerful but also, at least occasionally, the downtrodden. He was the lawyer for the petty criminal Clarence Gideon in the Supreme Court case of Gideon v. Wainright, which established criminal defendants' right to counsel. And he was Lyndon Johnson's lawyer, the man Johnson turned to whenever a problem was too vexing for his other advisers. Time after time, Fortas came through.

Johnson wanted a close ally on the Supreme Court, and so, in 1965, he convinced Arthur Goldberg to step down from the court to be the UN ambassador and nominated Fortas to replace him. Fortas was eminently qualified and quickly confirmed. He then served for the final three years of the Warren Court, joining the chief justice and Associate Justices Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and William Brennan to form a reliable liberal bloc.

In 1968, though, Johnson knew that his time in power was coming to an end, and so did Earl Warren. Warren feared that his bitter enemy Richard Nixon would succeed Johnson, and did not want Nixon to appoint his successor. Warren, therefore, agreed to resign while Johnson was president, and Johnson nominated Fortas to step into the position of chief justice. Given Fortas' prominence, his approval by the Senate just three years earlier, and the long history of Senate rubber-stamping Supreme Court nominees, one might have expected that Fortas' Senate confirmation to be chief justice would be a simple matter. It turned out to be anything but.

Bobelian explains at length the anger that conservative senators, especially southerners, felt at the Warren Court. Although Brown v. Board of Education, which ended the separate-but-equal doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, is today hailed as the Warren court's greatest achievement, and Warren is considered by many to be among the greatest chief justices in the court's history, large parts of the South felt that the decision was an assault on everything that they held dear. Conservatives were also incensed at the Warren court's rulings (like Gideon) granting criminal defendants' rights, which might allow defendants to escape punishment although they were plainly guilty. The court's first amendment rulings, which, in the minds of many conservatives, gave license to pornographers and communists who should have been punished, were another affront to their way of life. That the Warren court protected pornographers and communists but outlawed school prayer was an irony that the critics zestfully proclaimed, as if it, ipse dixit, established the court's folly.

All of the resentment bubbled over in Johnson's and Warren's attempt to allow Johnson to appoint Warren's successor and thus perpetuate the agenda of the Warren court. Senators fought against the nomination so fiercely that even Johnson, once the master of the Senate but now a lame-duck president, could not rein them in. Strom Thurmond, Sam Ervin, Robert Griffin and Richard Russell were among Fortas' prominent opponents, challenging him with hostile questioning in his confirmation hearings. Prominent conservative journalists and activists like James J. Kilpatrick, William F. Buckley, and Charles Keating (later to be involved in the Savings & Loan scandals of the 1980's) waged the campaign against Fortas in the public media. It was not a particular judicial decision, or doctrine, or event in Fortas' life that angered them. It was everything: the Democratic power play; the spread of civil rights, communism, and smut; the closeness of Fortas and Johnson; the power of the elite. This was not a narrow objection to a particular nominee. It was a revolt, and Fortas' nomination to be chief justice was the spark that set it off.

The nomination was eventually quashed by a filibuster. Warren stayed on the court until after Nixon was elected, and so Johnson was unable to replace him with a chief justice who would carry on his legacy. Instead, Nixon nominated Warren Burger to the position of chief justice, and the era of the Warren court ended.

Though he remained an associate justice on the Supreme Court, Fortas never recovered from the grueling battle. Less than a year later, he resigned from the court after it was disclosed that, while on the bench, he had received an annual payment of $20,000 from the not-for-profit association of Wall Street financier Louis Wolfson, who had been convicted of securities fraud. Fortas recused himself from any case involving Wolfson, but it appeared that, while a Supreme Court justice, Fortas had given Wolfson legal advice. Newly-elected President Richard Nixon, sensing the opportunity to appoint a replacement for Fortas, and thus continue the dismantling of the Warren court, encouraged a criminal investigation into Fortas' connection with Wolfson. Seeing the writing on the wall, Fortas resigned from the court. In his place, Nixon appointed Harry Blackmun, whom he (wrongly) expected would be a reliable conservative vote.

Bobelian, the judicial columnist for Forbes magazine, captures well the resentment that boiled over against Fortas. He convincingly demonstrates that the political battles that upset people in connection with the Garland and Kavanaugh nominations have roots as far back as Fortas' nomination. The themes from those recent battles–populists fighting against the Washington elite, the resentment of an imperial judiciary–also fueled the battle over Fortas' nomination.

While Bobelian succeeds in his broad purpose, his book is not as effective or compelling as it might have been, because it takes numerous detours into subjects tangential to the main story. Senator Everett Dirksen's background as an actor, Senator Thurmond's physical vigor and the career of James J. Kilpatrick, for example, are only some of the topics that get far more attention than is necessary for Bobelian to tell the story of Fortas' nomination. And Fortas' confirmation hearings, which should be the climax of his story, are not given the prominence that they deserve.

While Bobelian takes too many detours, he leaves largely unexplored a topic many readers may be interested in: What impact, if any, did Fortas being Jewish had on the fight over his nomination? Bobelian acknowledges that anti-Semitism may have played a role in the opposition to Fortas, but he barely explores the issue. It deserves more discussion. Fortas' Jewish identity was hardly a matter of indifference to those southerners who viewed his nomination as yet another step in the war by northern, liberal, cosmopolitan, intelligentsia against the native, southern way of life.

More important, Bobelian does not explore the deepest implication of his story. The choice of a Supreme Court justice may be the most significant decision that a President makes, not only because the Supreme Court issues rulings of great consequence, but because all federal judges have life tenure–thus, the incentive for presidents to select judges who are not only ideologically to their liking, but also young. Long after the president is gone, the justices whom he selected will carry on his legacy. Eisenhower famously declared that his selection of Earl Warren and William Brennan were his two biggest mistakes, and Ford has stated that his selection of John Paul Stevens was the most important accomplishment of his administration. Candidate Trump ran on the promise that he would populate the federal courts, especially the Supreme Court, with conservative judges. As president, he has carried out his promise.

There is so much riding on the choice of justice, and yet, as Bobelian demonstrates, the method of selection is the product of passion, anger, and politics–hardly the recipe for the best selections. It needn't be so. Although it will be impossible to remove politics from the selection and approval of Supreme Court justices, the selection could be made less consequential. Some have argued that Supreme Court justices should have term limits; others have proposed that justices should be appointed for terms of 18 years, with a new justice appointed every two years. See James DiTullio and John Schochet, Saving This Honorable Court, 90 Virginia Law Review 1093 (2004); Steven G. Calabresi and James Lindgren, Term Limits for the Supreme Court: Life Tenure Reconsidered, 29 Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 769. Under the latter proposal, every two years, a new justice would leave the Supreme Court and a new one would join; each justice would serve for 18 years. After serving their 18-year terms on the Supreme Court, the justices would not cease being federal judges but would be assigned to other courts where there were vacancies, either the district courts or the appellate courts. Every president would be able to appoint two justices. By contrast, under the present system, whether a president has the opportunity to appoint a justice, and if so how many, depends on luck (do any justices step down during the president's term?) and politics (as the cases of Merrick Garland and Abe Fortas show).

It is not clear whether a constitutional amendment would be required to implement this proposal or whether it could be done through statute. That, of course, is a significant question. The point, though, is that the appointment of Supreme Court justices is a process in need of reconsideration, as the story of Abe Fortas' failed bid to be chief justice amply demonstrates.

Benjamin E. Rosenberg is a partner at Dechert in the New York office.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

The Public Is Best Served by an Ethics Commission That Is Not Dominated by the People It Oversees

4 minute read

The Crisis of Incarcerated Transgender People: A Call to Action for the Judiciary, Prosecutors, and Defense Counsel

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Coerced Confessions and the Burden of Proof Beyond Reasonable Doubt

- 2Attorneys ‘On the Move’: O’Melveny Hires Former NBA Vice President; MoFo Adds Venture Capital Partner

- 3'Skin in the Game': Lawyers Call for Pressure After American Airlines Crash

- 4Apple Files Appeal to DC Circuit Aiming to Intervene in Google Search Monopoly Case

- 5A Plan Is Brewing to Limit Big-Dollar Suits in Georgia—and Lawyers Have Mixed Feelings

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250