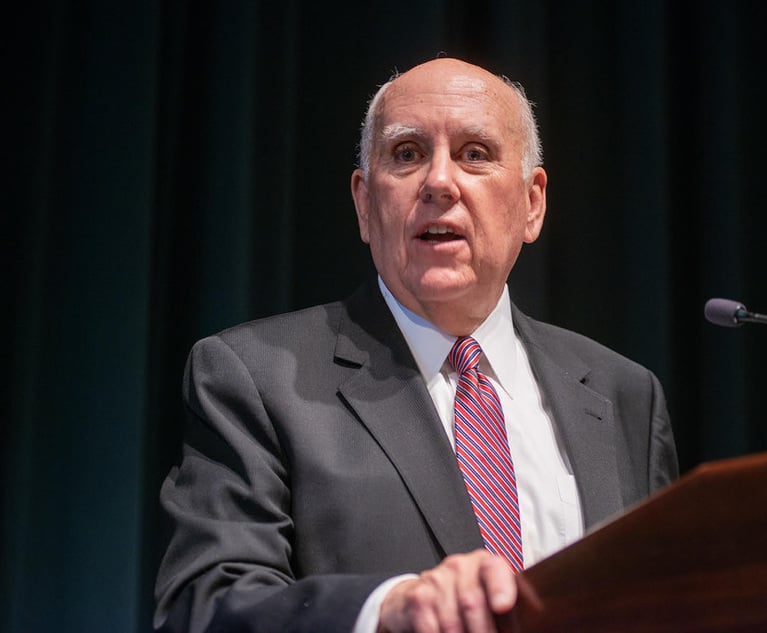

John Roberts Jr. Portrayed as Judge Who Draws Ire of the Left and Right

This book provides an excellent foundation upon which to build the public's understanding of the man who is already proving to be one of the most consequential chief justices in history.

May 17, 2019 at 06:21 PM

7 minute read

The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts

By Joan Biskupic

Basic Books, New York, $32, 432 pages

As the 14th year of his chief justiceship soon draws to a close, John Roberts, Jr., has at long last become the subject of a major biography, written by a veteran of the Supreme Court press corps, Joan Biskupic. The portrait she paints is of a judge who draws the ire of both the right and left. From the right, Roberts is criticized as being insufficiently conservative. From the left, he is derided as an activist who is too willing to eschew stare decisis when it conflicts with GOP doctrine. In the years to come, however, Roberts will not only continue to occupy the center chair, but in 5-4 decisions, he will also likely possess the deciding vote. In the author's view, the big question is whether he will work for the common ground or hew to his conservative roots.

The portrait painted by Biskupic fills only a part of the Roberts canvas. His tenure as chief justice may run for another two decades. Furthermore, although the author interviewed Roberts for 20 hours, he was very guarded. The full portrait of Roberts as a person and a chief justice will not emerge until his papers are opened to researchers. Until then, however, this book provides an excellent foundation upon which to build the public's understanding of the man who is already proving to be one of the most consequential chief justices in history.

As recounted by the author, Roberts' parents were natives of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. His mother, Rosemary, was a homemaker. His father, John (Jack) Roberts, Sr., served a lengthy management career at Bethlehem Steel. During Roberts' youth, his father was posted at large plants located in western New York and northern Indiana. After his 2008 death, Jack Roberts was remembered as being highly regarded by both steel company executives and United Steelworkers officials. As reported in the Baltimore Sun, he resisted the “us versus them” attitude.

During his formative years, Roberts grew up in comfortable suburban environments. According to the author, he was sheltered from much of the turbulence of the 1960s.

In high school, Roberts attended an Indiana Catholic academy for boys, the La Lumiere School, where he excelled. Early evidence of Roberts' conservatism emerged at La Lumiere. During the 1970s, Catholic high schools in the Midwest increasingly moved to a co-educational format. When La Lumiere considered admitting females, Roberts voiced his objections in the student newspaper, editorializing that “the presence of the opposite sex in the classroom will be confining rather than catholicizing.”

Roberts graduated from Harvard College in three years. He majored in history, winning top honors for essays on Marxism and Daniel Webster. Then, as now, liberal Harvard undergraduates outnumbered the conservatives. Experiencing an unsettling “kind of culture shock,” Roberts recounted that “Harvard was a lot different than Indiana” and he “reacted against the orthodoxy.”

At Harvard Law School, Roberts earned a coveted place on the Harvard Law Review. In early 1978, classmate David Leebron was elected president of the review. In choosing his managing editor, Leebron stated that he looked for “talent, diligence, and integrity.” He chose Roberts, stating that he “hit all three of those at the highest level.”

Following law school, Roberts served in prestigious judicial clerkships for Henry Friendly and William Rehnquist. Friendly was considered a “conservative in the traditional mold, judicially restrained and reserved, but not always agreeing with either the judicial or political right.” On the other hand, the conservative Rehnquist “approached the docket from a clearly conceived ideological perspective.” The author writes that, when “he became a judge himself, Roberts would identify in public statements with Judge Friendly's neutral legal approach even as his own opinions aligned more with Rehnquist's.”

According to the author, Roberts “was captivated by Ronald Reagan's [1980] presidential campaign.” Aided by Rehnquist, Roberts was hired as a special assistant to Reagan's first Attorney General, William French Smith. In this post, he wrote memoranda on voting rights, church-state disputes, women's rights, abortion rights and affirmative action that not only challenged the status quo, but also GOP officials “who were not, in his view, sufficiently committed to the Reagan agenda.”

In 1982, Roberts moved to Reagan's White House Counsel's Office, which was headed by Fred Fielding. Nicknamed “Owl,” Roberts was considered a peerless writer and possessed of a “steel-trap memory.” In a 2016 interview, Fielding told the author that Roberts' “ideological commitment had been shaped by his youth in Indiana, by his family, and by his Catholicism.”

In 1986, Roberts entered private practice at Hogan & Hartson, where he remained until 1989, when he was hired as the “political deputy” to Solicitor General Kenneth Starr. This post raised Roberts' “visibility among powerful conservatives.” One of his key cases was Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, in which he “developed arguments against government policies that gave a boost” to minorities. According to the author, Roberts as a lawyer and a judge has consistently “rejected group-based remedies and believe[s] that individuals who [have] faced bias should be able to sue only for specific instances of discrimination.”

In 1993, Roberts returned to Hogan & Hartson, where over the next 10 years he developed a premier appellate practice in which he argued 39 cases before the Supreme Court.

After a two-year stint as a D.C. Circuit judge, Roberts was confirmed as the 17th chief justice in 2005, replacing Rehnquist. According to the author, Roberts has tirelessly worked throughout his chief justiceship to protect the court's reputation and legitimacy against the charge that it is a partisan institution. In the wake of Bush v. Gore (2000), it has been a tough sell. “We don't work as Democrats or Republicans,” he told a 2016 audience. The author surmises that Roberts probably views the idea that judging is separate from politics as both a fiction and an aspiration.

The author observes that Roberts is a formidable strategist, possessing an “uncanny ability to size up a situation and calibrate his responses.” She notes that longtime associates compare him to a “master of three-dimensional chess” who anticipates all of his opponents' possible moves.

The best part of the book discusses National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012), in which Roberts cast the decisive vote that saved the Affordable Care Act. The author includes new material about Roberts' maneuverings to broker a deal with Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan to uphold the law's individual mandate as a permissible exercise of Congress' taxing power in exchange for their votes to invalidate the law's Medicaid expansion. Because Roberts' vote saved President Barack Obama's premier legislative achievement, conservatives branded him a traitor.

The author also does a creditable job analyzing the conservative voting record Roberts has produced in cases involving race, voting, religion and campaign finance. Unlike “movement” conservatives such as Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, Roberts' record as a lawyer and a judge indicates that he prefers incremental change, not revolutionary change.

In cases involving race, the author posits that Roberts is uncompromising, believing that the Constitution is “color-blind,” a concept first elucidated in Justice John Marshall Harlan's dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). As documented throughout the book, Roberts' views on race have remained consistent since the Reagan Administration. He has compared programs that benefit minorities to the segregation that was prohibited in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Roberts' most challenging assignment in protecting the court's reputation and legitimacy as a non-partisan institution may come in the next term if the court is asked to resolve any number of constitutional standoffs between President Donald Trump and Congress. It will be a telling moment.

Jeffrey M. Winn is an attorney with the Chubb Group, a global insurer, and the secretary to and a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

For Safer Traffic Stops, Replace Paper Documents With ‘Contactless’ Tech

4 minute read

Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley: American Painters in London

8 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250