Radiologist's Duty Has Evolved

Standards of care have evolved to embrace far more than the very circumscribed and limited role urged by a recent columnist.

May 17, 2019 at 11:00 AM

5 minute read

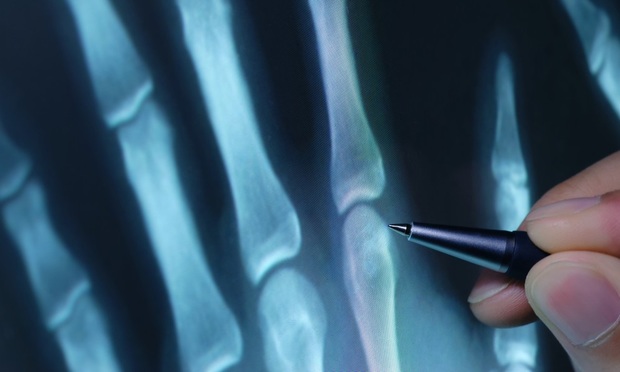

While I greatly respect your medical malpractice defense columnist John L.A. Lyddane, I am compelled to contest a significant part of his May 15th column, “Duty as a Question of Law in Medical Malpractice Defense,” specifically insofar as he represents that a radiologist's duty of care ends when he/she writes an accurate report. The duty does not “extend … beyond the obligation … [to] correctly interpret and document the findings” on a given radiological study, he says. That simply does not accurately reflect modern standards of care, even as published in the guidelines of the American College of Radiology (ACR).

While I greatly respect your medical malpractice defense columnist John L.A. Lyddane, I am compelled to contest a significant part of his May 15th column, “Duty as a Question of Law in Medical Malpractice Defense,” specifically insofar as he represents that a radiologist's duty of care ends when he/she writes an accurate report. The duty does not “extend … beyond the obligation … [to] correctly interpret and document the findings” on a given radiological study, he says. That simply does not accurately reflect modern standards of care, even as published in the guidelines of the American College of Radiology (ACR).

To support his contention, he cites, inter alia, a more than 30-year-old decision by the Court of Appeals in Alvarez v. Prospect Hospital, 68 N.Y.2d 320 (1986). There, a radiologist correctly interpreted a barium enema as showing a neoplasm (cancer) and sent his written report to the referring physician who had ordered the test. The radiologist did not, however, take any other steps to communicate with that physician or to in any way alert the patient to that ominous finding.

Critical to this discussion, Alvarez was decided on a record in which plaintiff did not submit any expert proof in opposition to the evidence proffered by defendant, who submitted his own deposition testimony explaining how he had met applicable standards of care by simply preparing a report which had accurately interpreted the study. In opposition, plaintiff's counsel simply argued in his own affirmation that the radiologist had breached all applicable standards of care. Hence, there was no admissible proof as to any departure, nor as to proximate cause and the Court of Appeals granted summary judgment to the radiologist.

This argument purporting to so narrowly circumscribe the duty of the radiologist is a common one espoused by defense counsel in malpractice cases and it is routinely based upon Alvarez, as well as some of the more recent cases referenced by Mr. Lyddane. However, it does not stand, as a general proposition, when confronted with a proper record in which appropriate expert proof has been offered. Indeed, in a case arising from facts strikingly similar in many ways to Alvarez, Supreme Court flatly rejected this argument,

holding that issues of fact existed as to just what the radiology standards of care required the radiologist to do in “communicating” such “unexpected positive findings” or “new clinically significant findings” to a referring clinician. See Kljyan v. Anonymous Physician, 57 Misc.3d 1222(A) (Sup. Ct., N.Y. Cnty., Joan A. Madden, J.), flatly rejecting this precise argument.

There, our client, only 49 years old, was referred by his urologist for a CT-scan of the abdomen as part of a workup for kidney stones. The radiologist correctly interpreted the study, also unexpectedly finding that there was “a soft tissue mass suspicious for a colonic neoplasm.” He testified at deposition that he had tried to telephone the referring clinician that Friday evening but did not reach him and left no substantive message regarding his surprise findings. He then faxed the report and there was no question it had been received at the urologist's office. Tragically, the urologist never read the critical finding of the mass, which was on the second page of the report; hence, he never followed up on it. It was only some 19 months later that the cancer was finally diagnosed for unrelated reasons. By then it had metastasized widely and despite aggressive treatment, plaintiff passed away.

In addition to suing the referring physician, we sued the radiologist's facility for its vicarious liability for his departures. We offered a detailed affidavit by a board certified radiologist with a long academic career that the very standards of the ACR required that in the presence of such “unexpected positive findings” or “new clinically significant findings”—of the same type as in Alvarez—the radiologist had a duty far beyond just reporting the findings correctly, specifically that he was required personally to make certain that the referring clinician had been made aware of the findings and of their clinical significance.

The difference from Alvarez—determinative in all respects—was the submission to the court of admissible proof as to that standard of care and the manner in which it had been breached by the radiologist. While defendants' skilled counsel offered precisely the argument by your columnist, relying, in fact, on a number of the cases cited in his column, Judge Madden ruled that there were “significant issues of fact” as to whether the “mode of communicating [by defendant radiologist] was sufficient given the 'unexpected positive findings' or 'new clinically significant findings' contained in the report.” (emphasis added) Summary judgment was denied.

The modern view—as articulated in the published ACR guidelines—has long since recognized that such critical pathology findings on a radiology study require communication by the radiologist well beyond just printing out and sending a report correctly describing those findings. While there may yet be some debate within the radiology community as to how, when, to whom and by whom such communication must be effected, the specialty has certainly recognized the enormous advances in diagnostic methodologies in recent decades and, consequently, the far more frequent discovery of pathologies which in years past might have gone undetected. Thus, its standards of care have evolved to embrace far more than the very circumscribed and limited role urged by your columnist.

David B. Golomb is a past president of the New York State Trial Lawyers Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Attorney Responds to Outten & Golden Managing Partner's Letter on Dropped Client

3 minute read

Letter to the Editor: Law Journal Used Misleading Photo for Article on Election Observers

1 minute read

NYC's Administrative Court's to Publish Some Rulings in the New York Law Journal Is Welcomed. But It Should Go Further

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Courts Grapple With The Corporate Transparency Act

- 2FTC Chair Lina Khan Sues John Deere Over 'Right to Repair,' Infuriates Successor

- 3‘Facebook’s Descent Into Toxic Masculinity’ Prompts Stanford Professor to Drop Meta as Client

- 4Pa. Superior Court: Sorority's Interview Notes Not Shielded From Discovery in Lawsuit Over Student's Death

- 5Kraken’s Chief Legal Officer Exits, Eyes Role in Trump Administration

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250