Contemplating the Larger Than Life Impact Judith Kaye Had on NY Courts

The memoir portion of the book is both engrossing and guarded. It was written in Kaye's final years after she became afflicted with the lung cancer that eventually took her life. Looking back from the high hill of her mid-seventies, she realized that the time to write about your life is when the end is near, beginning the story when you know the end.

May 29, 2019 at 04:28 PM

10 minute read

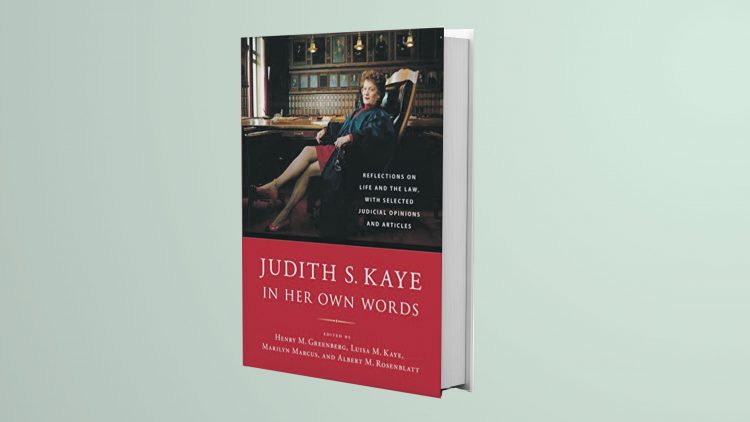

Judith Kaye in Her Own Words: Reflections on Life and the Law, With Selected Judicial Opinions and Articles

Judith Kaye in Her Own Words: Reflections on Life and the Law, With Selected Judicial Opinions and Articles

By Judith S. Kaye

Edited by Henry Greenberg, Luisa Kaye, Marilyn Marcus and Albert Rosenblatt

Excelsior Editions of the SUNY Press, New York, 544 pages, $39.95

In the history of the New York state courts, few have left a larger mark than Judith Kaye, the first woman appointed to the Court of Appeals (1983-1993) and the first to serve as chief judge (1993-2008). According to former Associate Judge Howard Levine, she was “a singular force on the court” and “no one will ever match her achievements as chief judge.” Now, three years after her 2016 death, Kaye's memoir and a curated selection of her judicial opinions, published articles and speeches have been collected into a well-organized book which covers the story of her personal and public lives. It is a worthwhile book that not only chronicles the life of this extraordinary jurist but also evidences the transformative effect that women such as Kaye have had on the legal profession.

The memoir portion of the book is both engrossing and guarded. It was written in Kaye's final years after she became afflicted with the lung cancer that eventually took her life. Looking back from the high hill of her mid-seventies, she realized that the time to write about your life is when the end is near, beginning the story when you know the end.

The book has four esteemed editors, one of who is Kaye's daughter, Luisa. Of the memoir, Luisa writes that, at the time of her mother's death, the manuscript had not yet been shaped “into a more conventional, chronologically ordered autobiography.” Some parts had been edited, while others had not. Ultimately, the decision was made to go with the original manuscript, “to preserve [Kaye's] voice over what would have perhaps been a neater but less genuine read.”

As such, the memoir is organized into three parts. It begins with the Court of Appeals years (1983-2008), then segues into her post-court years, and finishes with the formative years of her life and in the profession. Although unorthodox, the structure works. Kaye's voice and wit shine brightly, reflecting both “her thinking and priorities.”

Born in 1938, Kaye was the daughter of Ben and Lena Smith, Polish Jews from Drahichyn who emigrated to the U.S. and settled in Sullivan County. The nativist-inspired Immigration Act of 1924 made it difficult to emigrate legally from Eastern Europe. Kaye writes that in the 1940s, her father's “illegal status” was discovered and “there was trouble,” but the fact that her “parents were farmers with American-born children enabled them to secure citizenship. Where would we have been today, I wonder.”

At age 6, Kaye's family moved to Monticello, where they operated a dry goods store. During her girlhood, she recalled working in the store “from the time her nose reached the counter.” Along the way, she learned people skills and attention to detail, stating that to this day “no one wraps a gift package better than I do.” She also writes that Ralph Lauren's family (also from Drahichyn) summered nearby, and he reminded her years later that he actually “bought his first pair jeans in her parents' store.”

A precocious student, Kaye graduated from high school at age 15 and became the first Monticello student to attend Barnard College. She majored in Latin American civilizations and was determined to become a journalist. But when she graduated at age 20, the only employment she could find as a journalist was as a “social reporter for the Hudson Dispatch of Union City, New Jersey.”

Inspired by Anthony Lewis, who while in law school began reporting on courts for the New York Times, Kaye decided to attend night law school at NYU “simply to garner some serious attention in the world of journalism.” She writes that her parents were against “this zany idea,” but by her second year, she had earned a full scholarship. While at NYU Law, she recalls that there were no women professors, men dominated the classroom, and women were not allowed to live in the dormitory. Although the NYU Law Class of 1962 numbered about 290, only 10 were women. Undeterred, Kaye finished sixth in her class.

Unlike other prominent women law school graduates of that era, such as Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Kaye was able to obtain employment at a top firm, Sullivan & Cromwell, where she was posted as the only woman in the litigation department. It was there that she met her future husband, Stephen. The couple was married in 1964, and both left the firm. Stephen moved to Proskauer, where he enjoyed a long and distinguished career. Kaye moved to an in-house legal post at IBM, but was forced to resign in 1965 after becoming pregnant with her first child.

Between 1965 and 1969, Kaye bore three children but worried about the “toehold” she had gained in the profession, fretting that “if I left for any time I would never be able to return.” Good fortune soon struck, however, when she landed a post as the research assistant for Dean Russell Niles of NYU Law, who was soon installed as the new president at the New York City Bar Association. At the City Bar, Kaye became Niles's assistant and did stimulating work on an “amazing array of speeches and articles.” She writes that her City Bar service broadened her, because “[e]very significant issue in the law, in one form or another, hits the City Bar Association.” Years later, she served on its executive committee.

By the late 1960s, Kaye yearned to become a practicing lawyer again. She was hired as an associate in the commercial litigation department at the all-male Olwine, Connelly, Chase, O'Donnell & Weyher. She became the firm's first woman partner in 1975, and remained until her appointment to the Court of Appeals in 1983. She writes that, ironically, most of her practice was in federal court, “escaping pre-Commercial Division state court at every opportunity.” One client she developed at the firm was the Singer Co., for which she earned a win before Judge Edward Weinfeld, who complimented Kaye on her performance in open court. Kaye states that she framed that page of the transcript, “which to this day hangs on my office wall.” She also writes that there is nothing “quite as sweet as trouncing the adversary for your own client.” Because she had been there, Kaye understood the practicing lawyer.

During her 25 years on the Court of Appeals, Kaye authored 627 opinions, 522 of which were majority opinions. Inspired by Justice William Brennan, Kaye invoked the New York Constitution when it provided greater protections for civil liberties than the U.S. Constitution, a subject on which she delivered a celebrated City Bar speech in 1987. During her years as chief judge, she worked hard for unanimity and consensus, something that became harder after Governor George Pataki began making appointments.

The book includes 32 of her most meaningful opinions, including those dealing with the death penalty, libel, school funding, free speech, adoption rights for gay couples, gay marriage rights, search and seizure, separation of powers, insurance and the rights of battered mothers to retain the custody of their children. As an editorial plus, the presentation of each opinion is enhanced by a concise introduction written by one of Kaye's former law clerks, including luminaries such as Jennifer Schecter, Roberta Kaplan and Henry Greenberg.

Kaye treasured the Court of Appeals, and the events of late 1992 and early 1993 put her loyalty to the test. She writes that, soon after the 1992 presidential election, Bill Clinton considered appointing her to be the new U.S. attorney general. Meanwhile, the Court of Appeals was in flux after the downfall of Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, who Kaye had applied to replace. Choosing loyalty to the court in one of its most difficult hours, Kaye told Clinton she was remaining in New York. Then, months later, after Kaye had secured the chief judgeship, Clinton called again as he sought to replace the retiring Byron White on the Supreme Court. In response, Kaye again said no. Instead, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed to replace White.

A dominant theme of the book is Chief Judge Kaye, the reformer. The late Professor Derrick A. Bell once wrote that: “empathy foreshadows reform.” You must understand before you judge. As illustrated throughout the book, Kaye possessed a well-developed sense of empathy and was not afraid to show it.

Kaye was a champion for diversity in the profession and on the bench. She writes that a diverse judiciary enriches rather than prejudices court determinations. She laments that, even though women constituted about one-half of the law school graduates for the past 30 years, they still constituted only 15% of the equity partners in law firms and 25% of the bench.

Kaye states “unequivocally that the world would indeed be a better place with more women in leadership positions or with equal opportunity to reach them.” As an example, she identifies the Conference of Chief Justices, which includes one from every state. She writes that: “During my fifteen chief judge years, as I watched the composition of the nationwide Chief Justices Conference genderize, I saw shifts in approaches such as restorative justice, problem-solving courts and children's commissions. In my mind, I cannot disconnect initiatives such as these from the rising number of women chiefs.”

The best part of the book discusses what should prove to be Kaye's greatest legacy, which are the many court system reforms undertaken during her chief judgeship. Among other things, she made jury service more equitable (by eliminating most automatic exemptions), established the Committee on the Profession and the Courts (and the CLE requirement), and created and sustained the Commercial Division.

As noted by Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman (2009-2015), however, Kaye's greatest accomplishment as chief judge was the creation of several types of specialized problem-solving courts, including the misdemeanor drug court, integrated domestic violence court and various community courts. Writing in the NYU Law Review, Lippman wrote that she “started a revolution” which “redefined the traditional role of the judiciary in addressing difficult social problems reflected in our record-breaking court dockets: drug abuse, family violence and dysfunction, mental illness and so many more.”

In 1974, Robert Caro's The Power Broker compelled New Yorkers to take stock of how Robert Moses had changed their city over the past half-century. In 2019, if we take stock of the state of the legal profession and the New York courts, it is useful to understand Judith Kaye's life, career, accomplishments, and impatience with injustice. This book will promote that understanding.

Jeffrey M. Winn is an attorney with the Chubb Group, a global insurer, and serves as the secretary to and as a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

A Time for Action: Attorneys Must Answer MLK's Call to Defend Bar Associations and Stand for DEI Initiatives in 2025

4 minute read

The Public Is Best Served by an Ethics Commission That Is Not Dominated by the People It Oversees

4 minute read

The Crisis of Incarcerated Transgender People: A Call to Action for the Judiciary, Prosecutors, and Defense Counsel

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1An Eye on ‘De-Risking’: Chewing on Hot Topics in Litigation Funding With Jeffery Lula of GLS Capital

- 2Arguing Class Actions: With Friends Like These...

- 3How Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

- 4Fried Frank Partner Leaves for Paul Hastings to Start Tech Transactions Practice

- 5Stradley Ronon Welcomes Insurance Team From Mintz

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250