Leaving Them Speechless: A Mere Government Agency Cannot Silence Americans for Life

Within moments, lives are forever altered, reputations destroyed, businesses put on the road to ruin with many livelihoods at risk.

June 04, 2019 at 05:40 PM

5 minute read

When government agencies such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) bring charges, their press releases are notorious for their high visibility and inflammatory rhetoric. Within moments, lives are forever altered, reputations destroyed, businesses put on the road to ruin with many livelihoods at risk. What is less understood by the public—though widely known to securities insiders, courts and the commissions—is that sometimes these charges are flimsy, uncorroborated, based on compromised evidence or otherwise warrant a swift settlement when it becomes clear that the agency cannot make its case. In addition, the government can and does overcharge violations hoping some of it will stick.

Unsurprisingly, 98% of SEC cases settle. Fighting a powerful government agency is beyond the means of ordinary Americans. As SEC Commissioner Hester M. Peirce noted in 2018:

“Often, given the time and costs of enforcement investigations, it is easier for a private party just to settle than to litigate a matter. The private party likely is motivated by its own circumstances, rather than concern about whether the SEC is creating new legal precedent . . . . settlement[s are] negotiated by someone desperate to end an investigation that is disrupting or destroying her life.”

But what no one knows going into the process is that these agencies each require a gag order that suppresses forever your right to talk about your prosecution. If you later talk, the agency can reopen the case. What this means in practice is that the devastating, career-ending SEC publicity is the final word. Through this device, the agency locks in a complete and enduring win in the court of public opinion. Targets who settle their cases in order to stanch the costs of federal prosecution are left forever unable to defend themselves in the media.

This is profoundly dangerous and unconstitutional—and should be set aside by any court versed in the most elementary requirements of the First Amendment.

The SEC gag rule was slipped into the Federal Register in 1972—without prior publication, notice and comment. That alone renders the rule—and any administrative actions taken under its authority—unlawful. Amazingly, the rule itself doesn't say anything about silencing parties or reopened prosecutions. The rule itself simply asserts that “it is important to avoid creating, or permitting to be created, an impression that a decree is being entered or a sanction imposed, when the conduct alleged did not, in fact, occur.”

Think about this for a moment. The SEC doesn't want people thinking that it has punished people who might be innocent of some or all of the charges against them. From that wholly illegitimate motive, the SEC has arrogated power to itself to bind people who settle their charges to a lifetime of silence.

These agencies further know that these gag orders can silence truthful speech or even suborn perjury because their orders allow the gag to be lifted if the defendant is under oath—unless the agency is a party to the proceeding. That clever device keeps the agency's thumb on the scales of justice in its own cases, while conceding that in other tribunals the gag must be untied.

Congress cannot pass a law that provides that defendants who plea or settle must wear a lifetime muzzle because the First Amendment says: Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people … to petition the Government. And yet for nearly 50 years, a mere administrative agency has asserted to thousands of Americans that it possesses this power.

It does not. Long-established case law invalidates any such restrictions on speech. For this reason, the New Civil Liberties Alliance (NCLA) petitioned the SEC in October of 2018 to stop this illegal and unconstitutional practice. That petition prompted a Senate Banking Committee hearing in December 2018 in which SEC Chairman Jay Clayton was questioned about the policy.

NCLA has also recently brought an action in New York federal court to set aside one such gag order. Binding Second Circuit precedent from Crosby v. Bradstreet Co. holds that courts must set aside such prior restraint on speech, even when entered on consent, for a court is “without power to make such an order; that the parties may have agreed to it is immaterial.” It is long past time for Americans to stand up for their inalienable rights to free speech and put an end to this scandalous abuse of administrative power.

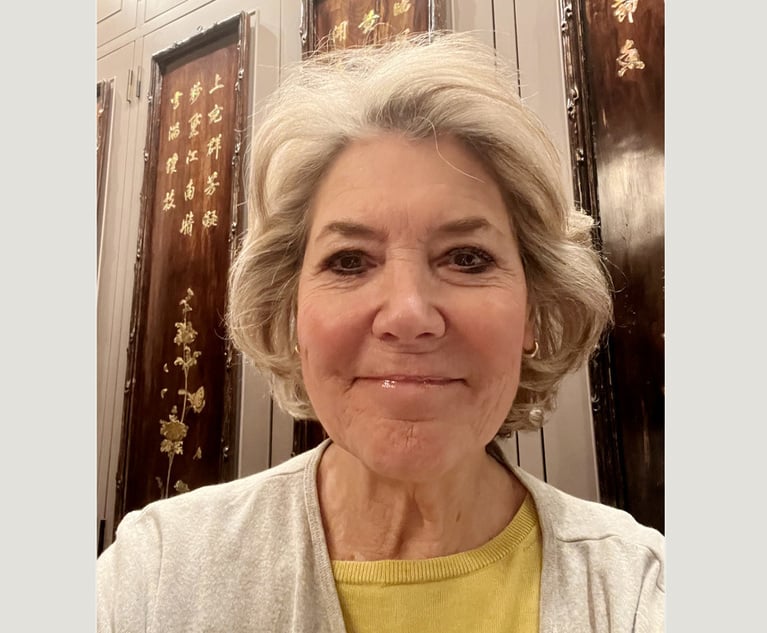

Peggy Little is senior litigation counsel at The New Civil Liberties Alliance which represents Barry D. Romeril in his challenge to the SEC's power to impose gag orders.

|This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Attorney Responds to Outten & Golden Managing Partner's Letter on Dropped Client

3 minute read

Letter to the Editor: Law Journal Used Misleading Photo for Article on Election Observers

1 minute read

NYC's Administrative Court's to Publish Some Rulings in the New York Law Journal Is Welcomed. But It Should Go Further

4 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250