What Happens to Whistleblowers When the Government Doesn't Intervene?

As the court stressed, "[i]f the government intervenes, the civil action remains the same--it simply has one additional party."

June 04, 2019 at 10:56 AM

4 minute read

In a long-anticipated decision–Cochise Consultancy Inc. v United States, ex rel. Hunt–the Supreme Court increased from 6 to 10 years the statute of limitations period for most whistleblowers bringing suit under the False Claims Act. The ruling greatly expands the potential exposure False Claims Act defendants face going forward.

In a long-anticipated decision–Cochise Consultancy Inc. v United States, ex rel. Hunt–the Supreme Court increased from 6 to 10 years the statute of limitations period for most whistleblowers bringing suit under the False Claims Act. The ruling greatly expands the potential exposure False Claims Act defendants face going forward.

But perhaps just as important, the decision provides a unanimous pronouncement by the Supreme Court that both intervened and non-intervened whistleblower cases are treated the same. This may prove useful for whistleblowers down the road in responding to the oft-made defense argument that non-intervened cases have less merit or should be viewed with skepticism.

The issue before the court was whether whistleblowers pursuing cases the government does not join are subject only to the traditional six-year limitations period, or whether they may also qualify for the expanded ten-year period to which the government has always been entitled (assuming it files within three years of learning of the violation). The Supreme Court stepped in to resolve a conflict among the Courts of Appeals which were all over the place on the question.

In a tightly worded opinion, relying largely on simple statutory construction, the court easily concluded the six and ten-year periods apply to both the government and whistleblowers. Any other reading, the court held, would undermine the plain text meaning of the statute. What this means for whistleblowers is significantly more time to bring a False Claims Act case and a much larger window of potential damages. Not a welcome result for the ever-increasing number of companies facing whistleblower actions where the government has chosen to sit on the sidelines.

But what may be an even more important outcome of the decision is the Supreme Court's reaffirmation of the legitimacy and importance of non-intervened whistleblower cases. The right of whistleblowers to go at it alone, though firmly embedded in the qui tam provisions of the statute, is under constant barrage. Defendants routinely play mischief with non-intervention decisions, urging courts to read into them a lack of merit or materiality of the claims.

With this recent decision, the Supreme Court offers a direct rejoinder to this line of attack by refusing to treat intervened cases and non-intervened cases any differently under the False Claims Act. Indeed, the court flatly rejected any reading of the statute that in any way depends on the government's intervention decision. As the court stressed, “[i]f the government intervenes, the civil action remains the same–it simply has one additional party.”

It is not surprising how the court came down here. The right to bring whistleblower actions in the name of the government is one of the hallmark provisions of the False Claims Act. It is a right Congress made clear it wanted whistleblowers to pursue, especially when the government decides to take a pass. That is why the statute provides for a significantly higher award to whistleblowers who proceed without government intervention (25-30% versus 15-25% of any government recovery).

What is surprising is that defendants continue to challenge this right or try to divine some kind of negative import when a whistleblower attempts to exercise it. Hopefully, this latest word by the high court powerfully reinforces not only the absolute right of the qui tam but the critical role Congress designed it to play as an essential part of the government's fraud enforcement regime.

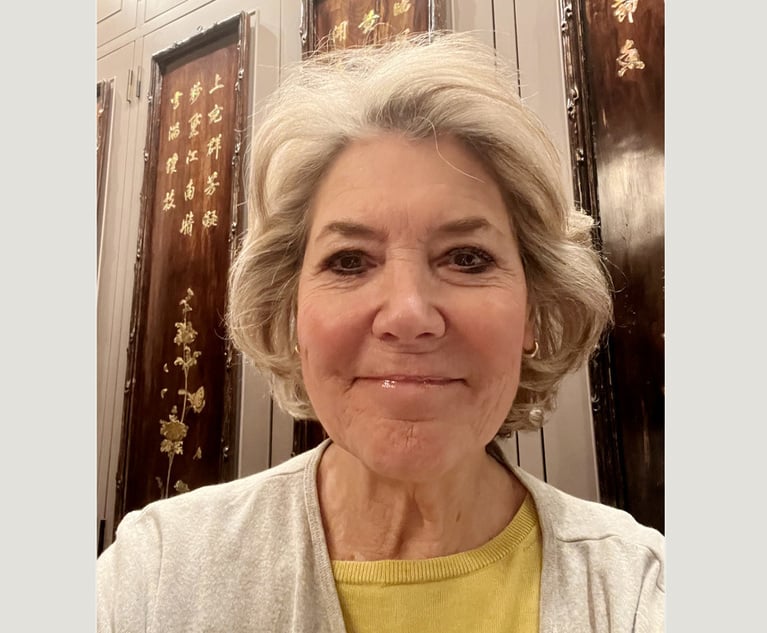

Gordon Schnell is a partner in the New York office of Constantine Cannon, specializing in the representation of whistleblowers.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Attorney Responds to Outten & Golden Managing Partner's Letter on Dropped Client

3 minute read

Letter to the Editor: Law Journal Used Misleading Photo for Article on Election Observers

1 minute read

NYC's Administrative Court's to Publish Some Rulings in the New York Law Journal Is Welcomed. But It Should Go Further

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 2States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 3Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 4Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 5Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250