At Age 94, J.P. Morgan's Grandson Reflects on World War II and Patterson Belknap

Having served the nation during the war there was a strong sense of idealism, a sense that a career in the law would provide opportunities to serve the community and nation which was on the cusp of becoming a world leader.

June 20, 2019 at 10:36 AM

8 minute read

Robert M. Pennoyer. Courtesy photo

Robert M. Pennoyer. Courtesy photo

I had grown up in privilege, living in Glen Cove near my grandfather J.P. Morgan who had a 47-room mansion on a 230-mile island in Long Island Sound. In 1915 during World War I, he had floated $3 billion in loans to England when she ran out of funds to buy munitions from America. This almost cost him his life. On July 4, 1915, a German national, believing he could stop the flow of munitions to England by killing the banker who supplied the money, taking two pistols, gained access to the mansion, confronted Grandpa at close range and fired both pistols, wounding him in the abdomen and thigh. He recovered, but from then on had a bodyguard of 24 ex-Marines patrolling the perimeter of his island.

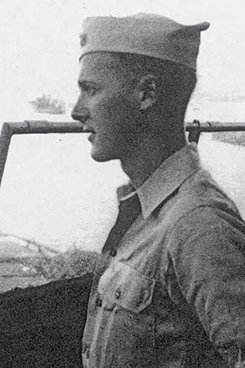

Robert M. Pennoyer, age 19, on duty in 1944 Photo courtesy of Robert M. Pennoyer

Robert M. Pennoyer, age 19, on duty in 1944 Photo courtesy of Robert M. Pennoyer

In 1917, when America went to war my father served with the Army in France.

In 1937 when I was 12, my father moved the family to Paris to head up the White & Case Paris office, putting me in boarding school in Switzerland. Over the next two years, I witnessed the Gathering Storm, saw Hitler annex Austria in March 1938, then Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland in September. We knew war was coming. The only question was when.

We came home a few weeks before September 1, 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland and England and France went to war. I wanted America to help England when she stood alone against Hitler.

After Pearl Harbor, my father at age 51 left White & Case to reenlist and spent four years supplying the air forces in China. In 1944 my brother Paul, a Navy flyer, won the Navy Cross for sinking a Japanese carrier.

In October 1944 at age 19, after two years at Harvard training in the Naval ROTC, I received an Ensign's commission and crossed the Pacific to join the cruiser Pensacola with the Seventh Fleet which became my home for almost two years. Over the coming months, we saw a lot of action, bombarding targets on Iwo Jima before and after the landing on February 19, 1945. The day before the landing my ship was heavily damaged, with almost 150 killed and wounded. A few days after the landing I heard a great cheer and, looking up, saw the broad stripes and bright stars on the flag moments after it was raised on the summit of Mount Suribachi, the four hundred foot hill at one end of the island. We did not know that we had witnessed a moment that would be recorded forever in our nation's history.

In late March we joined the task force for the invasion of Okinawa, where days of kamikaze attacks caused over 10,000 casualties in the fleet. We were never hit.

After the war, I found my vocation attending Columbia Law School on the GI Bill. Everyone had had some experience in the war. No one talked about it, but having served the nation during the war there was a strong sense of idealism, a sense that a career in the law would provide opportunities to serve the community and nation which was on the cusp of becoming a world leader. I left law school with a strong commitment to public service.

In 1952 the Republican Old Guard wanted to nominate Robert Taft, an arch isolationist, as a candidate for president. My friends and I believed that the nation needed Eisenhower who would engender the trust of our allies as America led the effort to contain the Soviet threat. Eisenhower was heading NATO in Brussels. We needed to persuade him to run.

I helped to organize Youth for Eisenhower. We rented Madison Square Garden for an Eisenhower rally. On the night of February 15, 1952, 8,000 young people, mostly veterans and their young wives and girlfriends, marched into the Garden chanting “We like Ike.” As they walked in under the brightly lit marquee they did not know they were being filmed. The film, flown to NATO headquarters, was shown to Ike in a darkened room. When the lights came on, with tears streaming down his face, he said, “I didn't know how much they cared.” Three weeks later he said he would be available to run.

After Eisenhower's election, in the spring of 1953, I became an assistant United States attorney under J. Edward Lumbard. Over the next few years, I tried about eight cases across a range of federal crimes and participated in a six-month investigation of corruption on the waterfront.

By mid-1955 it was time to leave. I wanted to learn what the nation was doing to contain the Soviet threat, and with incredible luck was appointed assistant to the general counsel in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Over the next four years, I had a number of challenging assignments that gave me an opportunity to serve President Eisenhower on several critical issues.

In 1956, an election year, at hearings on East-West trade before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (the McCarthy Committee), as instructed by the White House I directed career-level witnesses from the Pentagon to take the executive privilege and refuse to answer questions put by McCarthy, the ranking member, and his friend Bobby Kennedy who had succeeded Roy Cohn as Committee counsel. The anger was intense. We held the line, and the hearings went nowhere. (Excerpts from the transcript will be found in my memoir “As It Was.”)

Eisenhower, believing that overspending on Defense would weaken the nation, capped defense spending at $36 billion for three years. Some in the military, working with members of Congress, wanted to break the budget. In March 1956, Senator Symington, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, convened a subcommittee on air power and subpoenaed 100 uniformed military men to testify about the state of our defenses in top-secret hearings that lasted three months. General Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command, testified that we were procuring 600 B52s and that the nation would be in mortal danger in six to eight years unless we procured 2,000 B52s because of the Soviet's planned production of their long-range bomber, the Bison. (When the Soviet Union broke up we learned that the Soviets had produced only 34 Bison.)

I attended each day's hearing and worked with the ranking Republican, Senator Saltonstall, to make sure the record was complete. On a Friday afternoon after the hearings ended Symington handed Saltonstall the majority report to be given to the press on Monday, which cited only testimony that made our defenses sound weak. Saltonstall told me that for the press to receive the majority report without a minority report would have devastating consequences for Eisenhower's policies. Having indexed the 17,000-page transcript, by Saturday afternoon I was able to give him a draft minority report that quoted more senior officers across all three branches of the armed services who testified that our defense forces were adequate within an acceptable level of risk. Saltonstall said it was exactly what he wanted and would not change a word except to add a paragraph about the importance of civilian control. Both majority and minority reports were given to the press on Monday, and the president's budget held.

Returning to New York in 1958 I joined Patterson Belknap & Webb as an associate. The firm with 20 lawyers, including Robert Morgenthau and Robert P. (“Bob”) Patterson, a close friend from law school and the U.S. Attorney's office, already had a reputation for public service. Over the years I had an opportunity to help build the firm, which today has 200 lawyers.

In the 1970s the American Lawyer, which then measured firms only by the amount of money they made, predicted that “Patterson will be gone in five years because nice guys cannot last.” Then in 1977 Harold R. (“Ace”) Tyler, a close friend of Patterson's and mine from Columbia Law School and the U.S. Attorney's office, who had served as a federal district judge in the Southern District for 12 years, and as deputy attorney general under President Ford, joined us, adding his name to the firm. When asked why he had gone to a small firm like Patterson (we had about 40 lawyers) when he could have gone to any big firm in the city he told the press he wanted to be with friends and help build a firm that “has nowhere to go but up.”

Tyler helped to build a litigation practice second to none, and today the firm is thriving across all areas of our practice. But I am most proud of our culture that places high value on diversity and public service. Every lawyer is expected to take on pro bono assignments, and for at least the past decade, Patterson lawyers have recorded an average of 120-130 hours of pro bono time per lawyer, far more than many firms in the city.

Robert M. Pennoyer is a former chairman of Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler. He retired from the firm in 1995 but still comes to the office almost every day.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

‘Catholic Charities v. Wisconsin Labor and Industry Review Commission’: Another Consequence of 'Hobby Lobby'?

8 minute read

AI and Social Media Fakes: Are You Protecting Your Brand?

Neighboring States Have Either Passed or Proposed Climate Superfund Laws—Is Pennsylvania Next?

7 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250