U.S. District Judge Frederic Block Bares His Soul in New Book

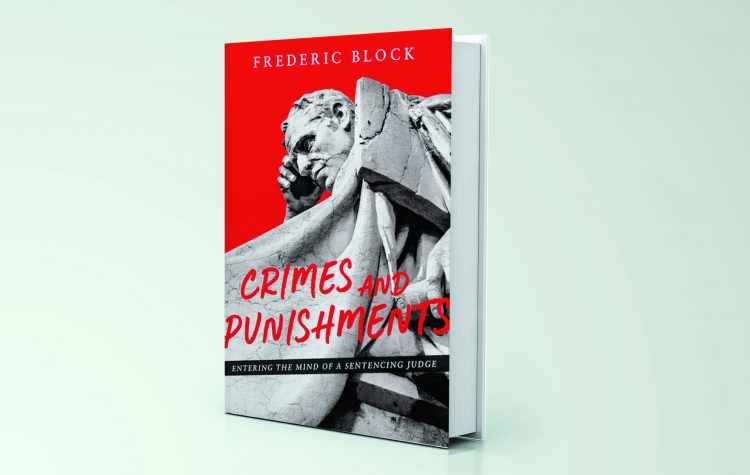

Crimes and Punishments: Entering the Mind of a Sentencing JudgeBy Frederic BlockABA Book Publishing, Chicago, 210 pages, $34.95Describing the…

June 24, 2019 at 02:30 PM

7 minute read

Crimes and Punishments: Entering the Mind of a Sentencing Judge

Crimes and Punishments: Entering the Mind of a Sentencing Judge

By Frederic Block

ABA Book Publishing, Chicago, 210 pages, $34.95

Describing the struggle between empathy and judgment, V.S. Naipaul once posited in an interview in The Atlantic that it is possible to do both, because “judgment is contained in the act of trying to understand.” This is the main theme of U.S. District Judge Frederic Block's new memoir, in which he explains the challenges of punishing people for criminal convictions. It is a book of great self-reflection, written in a plain and engaging style that is accessible to a wide audience. Because the author bares his soul and reveals his experiences, influences, and self-doubts, lawyers will find his authentic insights useful in better comprehending how he and other judges go about their work.

Expanding on issues addressed in his first memoir, Disrobed: An Inside Look at the Life and Work of a Federal Trial Judge (2012), the author's new book focuses on seven criminal cases, six in which he served as the trial judge, and one in which he sat by designation on a three-judge circuit court panel.

Prior to his 1994 appointment to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, the author was engaged in the private practice of law (1961-1994), where he handled both civil and criminal cases. In discussing the seven cases that are the subject of the book, the author masterfully weaves into the narrative countless war stories and personal experiences that he encountered in the profession before he joined the bench. From this narrative, it is clear that the author's 30-plus years of representing private clients provided him with a solid foundation from which to read and understand the lawyers and litigants who have appeared in his court.

As identified in the excellent forward written by Professor Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, five important criminal sentencing issues emerge from this book.

First, is the problem with draconian punishments and the point at which they become cruel and unusual in violation of the 8th amendment. Second, harsh punishments and mandatory minimum sentences have shifted too much power in criminal sentencing from the judges to the prosecutors. Third, defendants can lawfully be sentenced for crimes for which they were not actually convicted, and even for crimes for which they were acquitted. Fourth, the federal sentencing guidelines are too harsh and go too far in substituting uniformity for individualized sentencing. Fifth, there is a problem of race in the criminal justice system and the collateral consequences that result from a felony conviction.

The most compelling of these is the last one, in which the author recounts the case of Chevelle Nesbeth. She was arrested in 2015 at JFK Airport for smuggling 600 grams of cocaine in the rails of her suitcase, having returned from a trip to visit relatives in Jamaica. In 2016, a federal jury convicted her of felonies involving the importation of cocaine and the possession of cocaine with the intent to distribute. The sentencing guidelines indicated a prison term of 33 to 41 months.

In a 42-page opinion that drew nation-wide attention, the author refused to sentence Nesbeth to prison. Rather, he sentenced her to one year of probation, six months of house arrest and 100 hours of community service. In so doing, he called on the federal bench to examine closely how a felony conviction can negatively affect a person's life and concluded that the collateral consequences that Nesbeth would face as a felon constituted sufficient punishment.

In recounting this compassionate sentence, the author painstakingly details the evolution of his thinking. He begins by reminding the reader that over the years he has handled a large number of drug smuggling cases, given that JFK Airport is located in the Eastern District. He states that, in presiding over these cases, he has heard a lot of “bogus stories” from accused drug smugglers.

According to the author, however, five things about Nesbeth's case made it different. First, she was a working-class college student pursuing a career in education. Second, she had no prior criminal record. Third, she had no known history of drug use. Fourth, the manner in which the drugs were smuggled was novel, although he believed that the jury had reached the correct verdict. Fifth, prior to Nesbeth's case, he had just read Michelle Alexander's book, entitled The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.

Two of Alexander's arguments impressed the author. She convinced him that the large number of statutory collateral consequences facing ex-cons hindered their reintegration into society and the economy, resulting in a type of civil death. Furthermore, he also saw merit in her argument that the “War on Drugs” had disproportionately fallen on young African Americans, creating a class of persons who, when they emerged from prison, scarcely had more rights (and less respect than) freed slaves or a blacks who had lived under the Jim Crow laws.

Triggered by Alexander's book, the author asked his law clerks to research the collateral consequences issue. They found an American Bar Association database, which disclosed that there were more than 50,000 state and 1,500 federal provisions that imposed penalties, disabilities and disadvantages on ex-cons.

So enlightened, the author issued to the Nesbeth case lawyers a “homework assignment,” asking them to identify the specific statutory collateral consequences Nesbeth would face and opine on whether the court could lawfully introduce such collateral consequences as legitimate factors under the applicable sentencing regime.

In turn, this research revealed that Nesbeth's conviction: (1) suspended her eligibility for student assistance programs; (2) barred her from any federal grant, contract, loan, professional license or commercial license provided by an agency of or appropriated by funds of the U.S.; (3) rendered her ineligible for federally assisted housing, Social Security Act benefits, and food stamp benefits; (4) took away her right to a passport until her parole was concluded; (5) revoked or suspended her driver's license; and (6) precluded her from obtaining a teaching certificate.

Although heralded as groundbreaking by both liberals and conservatives, the Nesbeth sentence was controversial. As observed by the U.S. Attorney's office in Brooklyn, collateral consequences were “meant to promote public safety, by limiting an individual's access to certain jobs or sensitive areas,” and to limit government resources to “those who obey the law.”

Toward the end of the book, the author states that he is always concerned “where the line should be drawn in exercising my judicial power,” recognizing that it is his job to apply the law and the prerogative of the other branches of government to change it. In the end, however, he believes “it is my judicial responsibility to call attention to injustices that need to be fixed.”

The book also covers six other cases, including the author's sentencing of the mafia boss Peter Gotti, former state senator Pedro Espada, the Carreto Family of sex traffickers, a child pornographer, and several others. But it is the Nesbeth case which makes the book. In closing, the author suitably states: “I am often asked, as are most judges, which is the most important case you have ever handled. I always say it was Nesbeth.”

Jeffrey M. Winn is an attorney with the Chubb Group, a global insurer, and a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Distressed M&A: Safe Harbor Protection Extends to Overarching Transfer

Trending Stories

- 1Class Action Litigator Tapped to Lead Shook, Hardy & Bacon's Houston Office

- 2Arizona Supreme Court Presses Pause on KPMG's Bid to Deliver Legal Services

- 3Bill Would Consolidate Antitrust Enforcement Under DOJ

- 4Cornell Tech Expands Law, Technology and Entrepreneurship Masters of Law Program to Part Time Format

- 5Divided Eighth Circuit Sides With GE's Timely Removal of Indemnification Action to Federal Court

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250