Lawyers Retire, Move Out of Rural Upstate NY at Alarming Pace

"There are increasing challenges getting young lawyers to settle in these counties. They're carrying significant legal debt," said New York State Bar Association President Henry M. Greenberg. "In many of these communities, the justice gap is vast and this is a crisis."

July 01, 2019 at 01:09 PM

4 minute read

Scott Clippinger outside his office in Chenango County, where there aren't enough lawyers to meet the needs of clients.

Scott Clippinger outside his office in Chenango County, where there aren't enough lawyers to meet the needs of clients.

Photo: Margaret Brenner

Scott Clippinger, 76, operates his law practice out of the old hardware store in the tiniest municipality in New York State. ”I've always liked rural folk, and I always liked small towns,” he says.

But his daughters, who are ages 34 and 31 and also lawyers, have no taste for rural life, and nothing dad says will bring them back to the village of Smyrna. That explains, in a microcosm, the crisis affecting vast swaths of upstate New York. Rural justice is a quickly disappearing commodity.

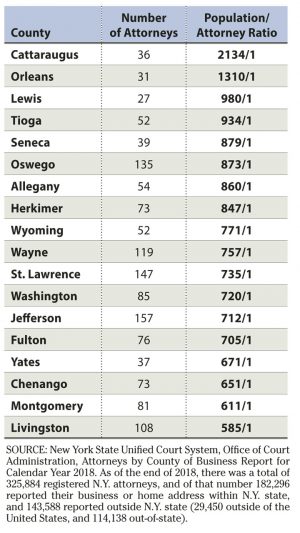

In 2007, 33 lawyers were in private practice in Chenango County, where Clippinger resides. Today, fewer than half remain. Eleven have retired, four have left the area, and four have died. While some still remain registered with the state, they are no longer active.

A survey by Albany Law School published in April shows the strain facing those left behind. Among its conclusions: Rural attorneys are overwhelmed by their caseloads, suffering financial stress and struggling with limited resources. Nearly half of those surveyed said there weren't enough attorneys for everyone who needs them.

And even more alarming to those who conducted the survey: 40% of those who responded said they were often unable to make referrals to other attorneys. Of those, 62% said they couldn't refer someone to another attorney because there was no one with the right expertise.

And even more alarming to those who conducted the survey: 40% of those who responded said they were often unable to make referrals to other attorneys. Of those, 62% said they couldn't refer someone to another attorney because there was no one with the right expertise.

In response to the shortage, the New York State Bar Association is about to announce the formation of a task force, and Clippinger is going to be a member.

Stan L. Pritzker, an associate justice on the Appellate Division, Third Department, and Taier Perlman, staff attorney at Albany Law School's Government Law Center and the author of its report on rural justice, will co-chair the task force.

Henry M. Greenberg, a shareholder at Greenberg Traurig and president of the state bar, said in an interview that he is calling on the task force to make suggestions for changes in laws and public policy in time for the April meeting of the House of Delegates.

“There are increasing challenges getting young lawyers to settle in these counties. They're carrying significant legal debt,” Greenberg said. “In many of these communities, the justice gap is vast and this is a crisis.”

Clippinger with his wife Judi, the legal administrator at the office. Photo: Margaret Brenner

Clippinger with his wife Judi, the legal administrator at the office. Photo: Margaret BrennerClippinger said law school debt makes attorneys less interested in pursuing a career in upstate New York. “As law school has become more expensive, they can't afford to live on the salaries that a rural practice can support,” he said.

Fred Ury, a founding member of Ury & Moskow in Connecticut and chair of the American Bar Association Center for Professional Responsibility Co-Ordinating Council, said the lack of attorneys in rural areas is only going to get worse.

He said there are already rural counties in Georgia with no attorneys whatsoever. Prosecutors and public defenders have to be brought in, and it's even more difficult to find a lawyer to handle a civil matter. Maine, too, has experienced a decrease in the number of lawyers, he said.

“We're going to be very challenged as we go down the road because there are a lot more lawyers retiring than are coming in,” he said.

More than half of the rural attorneys in the New York survey were at or nearing retirement age.

Responses like this were typical: “I am the only lawyer handling complex business transactions. I am 69 years old and cannot retire because too many people rely on me.”

Luckily for Chenango County, Clippinger doesn't want to retire anytime soon.

“I don't think free time is everything that it's cracked up to be,” he says.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

6 minute read

'Reluctant to Trust'?: NY Courts Continue to Grapple With Complexities of Jury Diversity

Trending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250