Warhol's Prince Works Don't Infringe on Photographer's 1980s Copyright, Judge Rules

Andy Warhol's 1984 "Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure," wrote a Manhattan federal judge in ruling in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation in the copyright infringement case. "The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith's photograph is gone.”

July 02, 2019 at 10:27 AM

6 minute read

Andy Warhol in 1976. Photo: Richard Drew/AP

Andy Warhol in 1976. Photo: Richard Drew/AP

In a copyright infringement lawsuit that could have potentially impacted thousands of Andy Warhol works found across the world, a federal judge on Monday ruled that the iconic artist made “fair use” of a 1981 photograph of Prince when he created a series of silkscreen images of the musician, including one that landed on the cover of Vanity Fair.

The lawsuit, lodged in 2017—about a year after Vanity Fair issued a commemorative issue of Prince that featured a Warhol image on its cover—pitted the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts against noted photographer Lynn Goldsmith.

According to Monday's decision by Judge John Koeltl of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Goldsmith contacted the Warhol Foundation in 2016—after spotting the Vanity Fair issue, which was released shortly after Prince's untimely death—and informed the foundation that she believed the cover infringed on one of her Prince photograph copyrights obtained in the 1980s.

According to Monday's decision by Judge John Koeltl of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Goldsmith contacted the Warhol Foundation in 2016—after spotting the Vanity Fair issue, which was released shortly after Prince's untimely death—and informed the foundation that she believed the cover infringed on one of her Prince photograph copyrights obtained in the 1980s.

The New York-based photographer also soon secured a copyright registration for one of her 1981 Prince photographs as an unpublished work, the judge noted.

In turn, the Warhol Foundation—which licenses Warhols, including his 16 Prince-image works created in 1984, for use by third-party publishers—lodged an action in federal court asking for a declaratory judgment stating that none of Warhol's 16 Prince-image works infringe on Goldsmith's 1980s Prince photograph copyright.

The foundation, according to its lawyer in the case, Luke Nikas of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, found itself suddenly fearing that hundreds or thousands of Warhols—often created using his famed silkscreen process that typically began with a photograph as a source—could be in danger of facing copyright infringement challenges coming from far and wide.

Meanwhile, Goldsmith—who Koeltl noted has photographed numerous musicians and performers throughout her career—responded to the foundation's action by asking for rulings of her own. Specifically, she and her lawyers asked Koeltl to deny the foundation's declaratory judgment request and to find that all of Warhol's 16 Prince-image works from 1984—14 of which were created using silk-screening—do, in fact, infringe on her 1980s Prince photograph copyright.

On Monday, Koeltl, in a carefully crafted 35-page opinion, ruled in the foundation's favor. He declared that no copyright infringement existed; and he also turned back Goldsmith's cross-summary judgment motion requests.

Koeltl explained in the decision's first half that he was expressly not finding whether the Warhol creations from 1984 were substantially similar to Goldsmith's 1981 Prince photograph. He need not make that finding, he said, because it was clear that, in this case, the Warhols at issue were protected by the statutory “fair use” defense.

The fair use defense, Koeltl noted, centers on “the critical question … of whether copyright law's goal of 'promot[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts would be better served by allowing the use [of a work at issue] than by preventing it,'” quoting CastleRock Entertainment v. Carol Publishing Group.

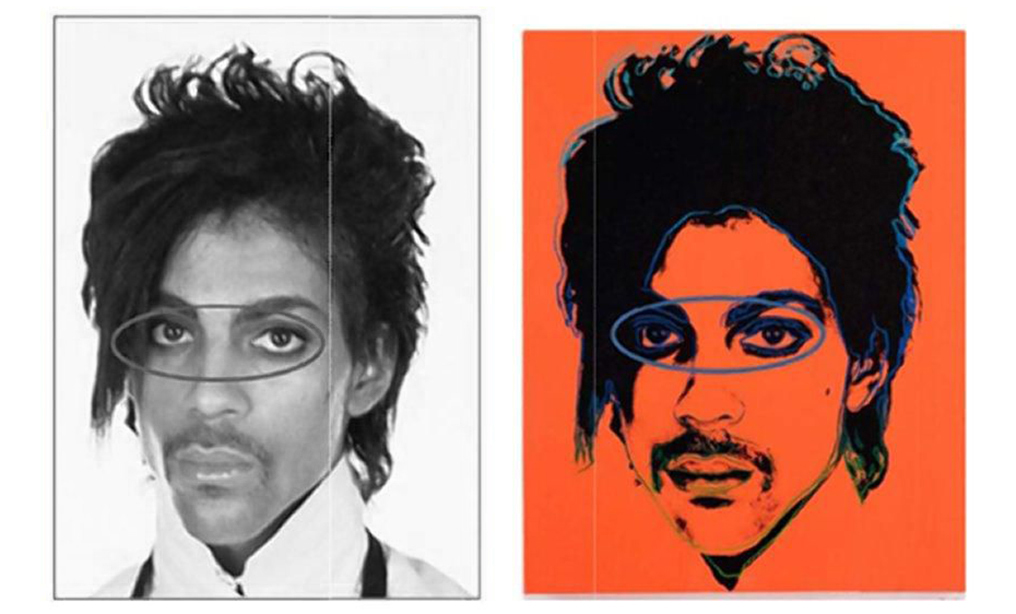

1981 Prince photograph by Lynn Goldsmith, left, and one of Andy Warhol's silkscreen images of the musician. Source: Court exhibitKoeltl went through analyzing the four factors underpinning a fair use defense and considered whether Warhol's 16 creations served the broader public interest by being out in the world, and whether the now-deceased Warhol had transformed the Goldsmith photograph of Prince into his own art.

“The foundation has made each of the sixteen works available for licensing to third parties, but also it gave four of the works to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, and some of the other works have been exhibited at other galleries and museums,” Koeltl noted, for instance.

Moreover, he said, the foundation “is a not-for-profit entity that was created for the purpose of advancing visual art, and profits derived from licensing Warhol's works help fund AWF's programs. Thus, although the Prince Series works are commercial in nature, they also add value to the broader public interest.”

Moving to another point of analysis, Koeltl wrote that “the [Warhol] Prince Series works are transformative, and therefore the import of their (limited) commercial nature is diluted.”

In explaining what made the works transformative or unique, Koeltl said, for example, that “Prince appears as a flat, two-dimensional figure in Warhol 's works, rather than the detailed, three-dimensional being in Goldsmith's photograph.”

“Moreover,” the judge continued, “many of Warhol's Prince Series works contain loud, unnatural colors, in stark contrast with the black-and-white original photograph. And Warhol's few colorless works appear as rough sketches in which Prince's expression is almost entirely lost from the original.

“These alterations result in an aesthetic and character different from the original,” Koeltl continued. “The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure. The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith's photograph is gone.”

On Monday evening, Nikas, the foundation's lawyer, said in a phone interview that “our core point was that Warhol is one of the most iconic artists and important artists of the 20th century, and these works represent his classic celebrity portraiture style, and we are pleased that the court upheld Warhol's practices as legally permissible.”

Nikas added that “the stakes of this decision were enormous.”

“Andy Warhol was known for referencing imagery in his works, not too different from these works,” the lawyer explained, “and if the court had not upheld the use in this case, it would have created the potential for serious challenges across the rest of his works.”

A different result from Koeltl could have “impacted potentially several billion dollars worth of Warhol's art across the world,” Nikas said.

Barry Werbin, a Herrick Feinstein partner who helped represent Goldsmith, made clear in an email Monday night that his side intends to appeal Koeltl's decision.

“Obviously we are disappointed with the fair use finding, which continues the gradual erosion of photographer's rights in favor of famous artists who affix their names to what would otherwise be a derivative work of the photographer and claim fair use by making cosmetic changes,” Werbin said.

He added that “the District Court was of course constrained by the Second Circuit's prior decision in Cariou v. Prince, which stretched 'transformative' fair use to new boundaries that we believe were not contemplated by Congress or the Supreme Court in its 1994 Campbell decision, where 'transformative' was mentioned for the first time in case law.”

“We are hopeful that an appeal to the Second Circuit will be successful and pull in the reins of transformative use where photography is concerned,” he said.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Prosecutors Ask Judge to Question Charlie Javice Lawyer Over Alleged Conflict

Trending Stories

- 1Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 2Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

- 3'We Neither Like Nor Dislike the Fifth Circuit'

- 4Local Boutique Expands Significantly, Hiring Litigator Who Won $63M Verdict Against City of Miami Commissioner

- 5Senior Associates' Billing Rates See The Biggest Jump

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250