International Litigation and Arbitration at the Supreme Court

In their International Litigation column, Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky look back at the international litigation and arbitration issues decided in the U.S. Supreme Court's most recently ended term, specifically, decisions relating to service of process under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, the immunity of international organizations, and class action arbitration.

July 24, 2019 at 11:45 AM

10 minute read

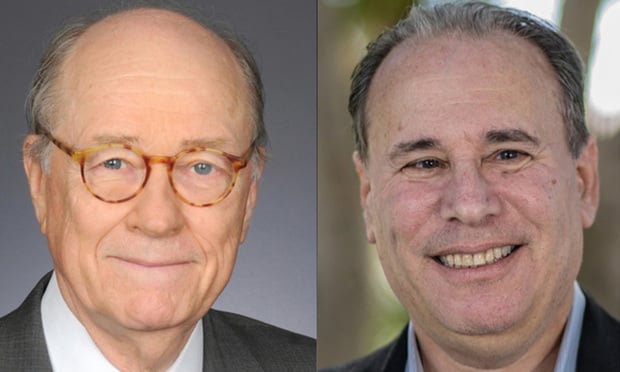

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

We occasionally use our July column to look back at the international litigation and arbitration issues decided in the U.S. Supreme Court's most recently ended term. In this month's column, we look at Supreme Court decisions relating to service of process under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), the immunity of international organizations, and class action arbitration. (Another important arbitration decision in this Supreme Court term, Henry Schein v. Archer and White Sales, No. 17-1272, 2019 WL 122164 (Jan. 8, 2019), was discussed in detail in our March 20, 2019 New York Law Journal column, “Competence-Competence: A Comparative Analysis.”) Interestingly, in all three, the Supreme Court reversed the respective circuit court.

Service of Process Under FSIA

Sudan v. Harrison, No. 16-1094, (March 26, 2019), was a lawsuit by victims of the bombing of the USS Cole who have been trying to hold the government of Sudan responsible for providing support to the al-Qaeda bombers who killed 17 sailors and injured 42 more in 2000. The FSIA generally immunizes foreign states from suit in the United States unless one of several enumerated exceptions to immunity applies. 28 U.S.C. §§1604, 1605-1607. The FSIA includes its own service of process regime, which works in step-like fashion, meaning that one goes to the succeeding service option once the prior one is unavailing. Here, the relevant service option was service “by any form of mail requiring a signed receipt, to be addressed and dispatched…to the head of the ministry of foreign affairs of the foreign state concerned.” §1608(a)(3).

The court clerk, at respondents' request, addressed the service packet to Sudan's Minister of Foreign Affairs at the Sudanese Embassy in the United States and later certified that a signed receipt had been returned. After Sudan failed to appear in the litigation, the district court entered a default judgment for respondents and thereafter issued three orders requiring banks to turn over Sudanese assets to pay the judgment. Sudan challenged those orders in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, arguing that the judgment was invalid for lack of personal jurisdiction, because §1608(a)(3) required that the service packet be sent to its foreign minister at his principal office in Sudan, not to the Sudanese Embassy in the United States. The Second Circuit affirmed, but the Supreme Court reversed.

The court relied on the plain language of the statute. A letter or package is “addressed” to an intended recipient when his or her name and address are placed on the outside. The noun “address” means “a residence or place of business.” A foreign nation's embassy in the United States is neither the residence nor the usual place of business of that nation's foreign minister.

The court also noted potential tension with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. If mailing a service packet to a foreign state's embassy in the United States should be sufficient, then it would be easier to serve the foreign state than to serve a person in that foreign state under Rule 4. The Supreme Court's decision avoided this “oddity.” The court also was mindful that the U.S. government supported the position of Sudan, in part because U.S. embassies do not accept service of process when the United States is sued in a foreign court, a practice that might be imperiled by a ruling against Sudan.

The Supreme Court recognized that there was unfairness to the plaintiffs, who, after nine years of litigation, would have to go back to square one. But, according to the court, “there are circumstances in which the rule of law demands adherence to strict requirements even when the equities of a particular case may seem to point in the opposite direction.”

Immunity of International Organizations

In Jam v. Int'l Fin. Corp., No. 17-1011 (Feb. 27, 2019), the Supreme Court held that international organizations are susceptible to suit in the United States, including in relation to their commercial activities. Respondent, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), is a member organization of the World Bank Group and a recognized international organization under the International Organizations Immunity Act (the IOIA). The IFC funds private-sector projects in developing countries.

The IFC financed the Tata Mundra power plant project in Gujarat, India by lending Coastal Gujarat Power Limited $450 million to finance the project. Petitioners, fishermen and farmers living near the Tata Mundra facility, sued the IFC in 2015 in federal court for damages and injunctive relief, asserting that the IFC, by failing to enforce a required environmental action plan as well as its own internal policies, had caused air pollution, groundwater contamination and displacement of petitioners and others similarly situated.

In response, the IFC argued that it was absolutely immune under the IOIA, which provides that international organizations “shall enjoy the same immunity from suit…as is enjoyed by foreign governments, except to the extent that such organizations may expressly waive their immunity for the purpose of any proceedings or by the terms of any contract.” When the IOIA was enacted in 1945, foreign governments were absolutely immune from suit, but sovereign immunity protections have changed over the years. With the passage of the FSIA, foreign sovereigns no longer had absolute immunity.

Most significantly, foreign governments are not immune from actions based upon certain kinds of commercial activity in which they engage. The IFC contended, however, that international organizations' statutory immunity remains absolute under the IOIA' s express terms (which had not been amended) and in accordance with previous cases interpreting the IOIA. The district court agreed with the IFC and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed.

The Supreme Court reversed and held that the IOIA affords international organizations the same immunity from suit that foreign governments currently enjoy under the FSIA. The court examined the language of the statute and focused on the phrase “same immunity from suit…as is enjoyed by foreign governments.” According to the court, such language does not establish a fixed level of immunity, absolute or otherwise. This was contrasted with another IOIA subsection, which did employ clearly static language to define the scope of other immunities for international organizations. The two subsections, when read together, suggested, the court said, that the immunity from lawsuits under the IOIA was meant to be dynamic.

In reversing the D.C. Circuit's decision, the Supreme Court remanded the case to the district court to permit the plaintiffs to attempt to establish that the IFC's conduct qualifies as the “commercial activity” that is excepted from the immunity conferred upon international organizations by the IOIA.

Jam represents a significant change in the law of international organization immunity. The Supreme Court tried to downplay the potential for the decision to open the floodgates to litigation against international organizations. It noted, for example, that international organizations may include near-absolute immunity in their charters if that should be necessary (as the United Nations does). In actuality, however, international organizations may face significant political or practical difficulties in amending their charters to erect heightened levels of immunity from suit.

Class Action Arbitration

The last case we look at, Lamps Plus, Inc. v. Varela, No. 17–988 (April 24, 2019), concerned class action arbitration. In 2016, a hacker tricked an employee of petitioner Lamps Plus, Inc. into disclosing tax information for about 1,300 company employees. After a fraudulent federal income tax return was filed in the name of respondent Frank Varela, a Lamps Plus employee, Varela filed a putative class action against Lamps Plus in federal district court on behalf of employees whose information had been compromised.

Relying on the arbitration agreement in Varela's employment contract, Lamps Plus sought to compel arbitration—on an individual rather than a class-wide basis—and to dismiss the suit. The district court rejected the individual arbitration request, but authorized class arbitration and dismissed Varela's claims without prejudice. Lamps Plus appealed and the U.S. District Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed. The Supreme Court reversed.

The Supreme Court had held in Stolt-Nielsen SA v. AnimalFeeds Int'l, 559 U.S. 662 (2010) that a court may not compel class-wide arbitration when an agreement is silent on the availability of such arbitration. According to the Ninth Circuit, however, Stolt-Nielsen was not controlling because the agreement in the case before it was ambiguous, rather than silent, on the issue of class arbitration. Certain language in the contract, the Ninth Circuit said, could support class arbitration, such as the following: “arbitration shall be in lieu of any and all lawsuits or other civil legal proceedings relating to my employment.” The Ninth Circuit, following California law, construed the ambiguity against the drafter, Lamps Plus, and adopted Varela's interpretation authorizing class arbitration.

The Supreme Court explained that the first principle underscoring all of its arbitration decisions is that arbitration is strictly a matter of consent. The consent touchstone is understandable because, under the Federal Arbitration Act (the FAA), arbitrators exercise only the authority they are given by the parties to the agreement to arbitrate.

Thus, the task for courts and arbitrators is to give effect to the intent of the parties. In doing so, they must recognize the “fundamental” difference between class arbitration and the individualized form of arbitration envisioned by the FAA. The court described the difference in this way:

In individual arbitration, parties forgo the procedural rigor and appellate review of the courts in order to realize the benefits of private dispute resolution: lower costs, greater efficiency and speed, and the ability to choose expert adjudicators to resolve specialized disputes. Class arbitration lacks those benefits.

In Stolt-Nielsen, the court held that courts may not infer consent to participate in class arbitration in the absence of an affirmative contractual basis for concluding that the parties agreed to do so. Silence is not enough. The Supreme Court applied the same reasoning here. Like silence, ambiguity does not provide a sufficient basis to conclude that parties to an arbitration agreement agreed to forego the principal advantage of arbitration.

The Supreme Court also addressed specifically the Ninth Circuit's reasoning based on the state law contra proferentem doctrine, under which contractual ambiguities should be construed against the drafter. That default rule, the Supreme Court said, is based on public policy considerations and seeks ends other than the intent of the parties.

Such an approach is flatly inconsistent with the foundational FAA principle that arbitration is a matter of consent. For these reasons, the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Ninth Circuit. Left undiscussed were other state law principles of contract interpretation that might be inapplicable under the same reasoning.

Supreme Court jurisprudence over the past few years has created a landscape in which businesses that include arbitration clauses in their contracts can effectively prevent class action lawsuits from their contractual counter-parties. The potential backlash will likely come by way of legislative measures, and even the title of a pending bill in Congress—the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal Act (the FAIR Act)—readily reveals the view of the bill's sponsors toward arbitration.

It is true that the political talk usually centers on measures to free employment and consumer agreements from compulsory arbitration, but, as the anti-arbitration wave grows, so does the possibility that commercial arbitration will be swept up in its wake. Commercial disputes lawyers, and especially those involved in international arbitration, must remain vigilant in monitoring proposed legislation to avoid its having an impact on arbitration as means of resolving commercial disputes.

Lawrence W. Newman is of counsel and David Zaslowsky is a partner in the New York office of Baker McKenzie. They can be reached at [email protected] and david.zaslowsky@bakermckenzie.com, respectively.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Judgment of Partition and Sale Vacated for Failure To Comply With Heirs Act: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Ex-Kline & Specter Associate Drops Lawsuit Against the Firm

- 2Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

- 3The Importance of Federal Rule of Evidence 502 and Its Impact on Privilege

- 4What’s at Stake in Supreme Court Case Over Religious Charter School?

- 5People in the News—Jan. 30, 2025—Rubin Glickman, Goldberg Segalla

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250