Looking Back on the Allen Ginsberg Obscenity Trial 62 Years Later

That we can celebrate the victory of 'Howl' over the censors today was by no means a forgone conclusion when the obscenity charges were brought.

August 26, 2019 at 02:19 PM

8 minute read

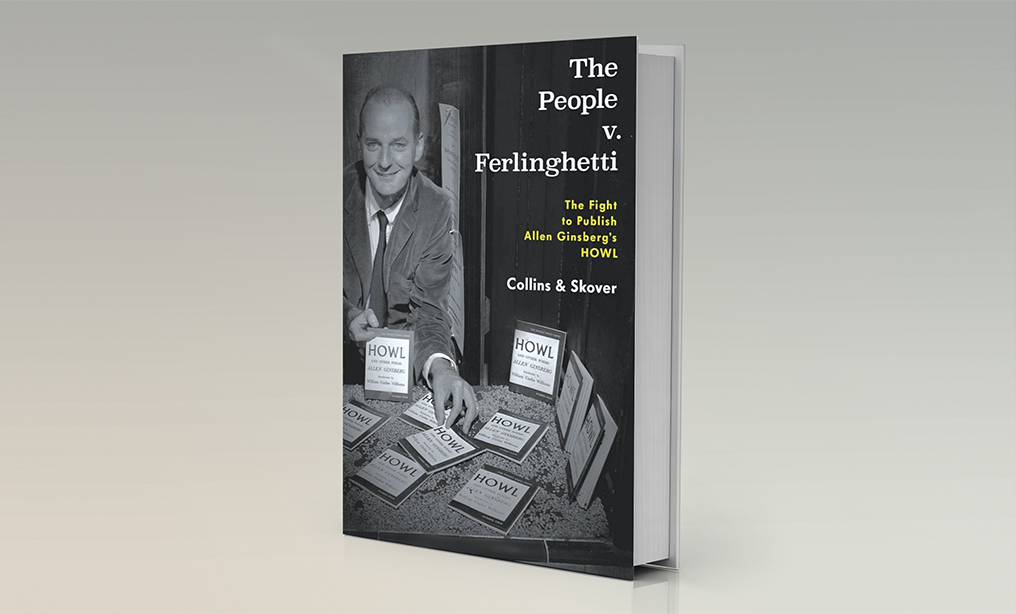

The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg's HOWL

By Ronald K. L Collins and David M. Skover

Rowman & Littlefield, $30

Sixty-two years ago this month, a decade before 1967's Summer of Love, San Francisco hosted the obscenity trial of Allen Ginsberg's epic poem, Howl, during the summer of 1957. The 1950s, and well into the 1960s, witnessed no shortage of censorship battles over the arts–even comic books. This particular battle focused on a small chapbook of obscure poetry, Howl and Other Poems, has reached quasi-mythological status in the history of the Beat Generation. The nationwide publicity generated by the trial single-handedly dragged Ginsberg and Howl into the public consciousness. The fight over Howl has been recounted many times and, in 2010, shortly after its 50th anniversary, a film of the trial made it to the big screen with James Franco in the role of Allen Ginsberg.

Today's global recognition and critical acclaim for Howl aside, that the trial itself still resonates in the legal community is no small accomplishment because the decision was never officially published. Moreover, it is unusual in and of itself for a municipal court trial judge to author a written opinion, which would be binding only upon those individuals within that municipality. As a consequence, People v. Ferlinghetti was never cited as precedent, or otherwise, in any subsequent legal proceeding. The slip opinion never found its way into the proverbial law books. While it was reproduced in numerous works about the trial, the subsequent version of the slip opinion was reported without the original internal legal citations.

One impressive feat the co-authors of "The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight to Publish Allen Ginsberg's HOWL," law professors Ronald K.L. Collins and David M. Skover, masterfully accomplished was to reconstruct the "as issued" 1957 opinion, with its original case citations fully restored. Collins and Skover are intimately familiar with the material because they covered the author, poem, and trial in their earlier, much broader work, "Mania: The Story of the Outraged and Outrageous Lives That Launched a Cultural Revolution." This slim new volume collects Mania's coverage of Howl and presents it in a straightforward, linear narrative. The text is just 105 pages but is amply supplemented with an addendum that includes the fully reconstructed opinion, a 2007 interview of Lawrence Ferlinghetti with Pacific Radio (on the trial's 50th anniversary), a timeline of Ferlinghetti's life and copious source notes on the material.

That we can celebrate Howl's victory over the censors today was by no means a forgone conclusion when the obscenity charges were brought. In fact, the trial was the government's second attempt to censor the book. Originally, in March 1957, the U.S. Customs Inspector seized 520 copies of the second printing of the book. The Customs Service had actually overlooked the first shipment of Howl and Other Poems, which had previously arrived without incident. After holding onto the shipment of books for two months, the United States attorney informed the customs inspector that he had decided not to prosecute the case. Therefore the seized copies of the book were formally released to the City Lights Bookstore.

In what might easily be viewed as an act of revenge, less than a week later two undercover police officers from the Juvenile Division purchased the copies of Howl from City Lights. Those purchases then became the basis of the obscenity prosecution. In no small irony, those initial copies of Howl had been printed with asterisks in place of the letters of the expletives contained in the book. Shigeoshi Murao, the clerk who sold the books to the undercover officers, was arrested and taken to jail for booking.

Ferlinghetti, the book's publisher, was at his cabin in Big Sur at the time and was not arrested. He turned himself in upon his return a week later. Allen Ginsberg, the author, was not even in the United States at the time and was not charged. Ginsberg was in Tangiers, Morocco, helping William Burroughs assemble his novel, Naked Lunch–a book which, itself, would be featured prominently in a number of future obscenity battles.

Ferlinghetti, concerned that the authorities might prosecute him for publishing Howl, had the foresight to line up the American Civil Liberties Union as pro bono counsel before the book was seized. The ACLU had, in turn, secured the services of Jake Ehrlich, one of San Francisco's most prominent criminal attorneys, to head the defense.

In all, with the addition of attorneys Al Bendich and Lawrence Speiser, a three-person pro bono legal team would defend Murao and Ferlinghetti. Where this book really excels is in the authors' discussion of the legal backbone of the process. It includes an analysis of the legal briefs filed by the defense team, trial strategy employed by both sides and the impact of Judge Horn's pre-trial rulings on the case. They also present the legal background of the prosecutor, defense counsel and the judge himself.

On the first day of the trial, Ehrlich suggested, and the judge readily agreed, that the case should be postponed until the judge had read Howl and the other poems at issue. The judge also dismissed the charges against Murao because, as the store clerk who rang up the purchases, the state could not prove the requisite criminal intent to win a conviction. For similar reasons, the judge also dismissed that portion of the charges that sought to hold Ferlinghetti responsible for the sale of copies of "The Miscellaneous Man," a book he had not published.

When the bench trial resumed after the week-long continuance, Judge Clayton Horn heard expert testimony from nine defense and two prosecution witnesses. A Sunday school teacher, Judge Horn had previously sentenced five shoplifters to watch "The Ten Commandments" and then write essays on the moral lessons they had learned from the film. Luckily, his openness to the legal issues presented in the Howl case did not align with the uniquely straight-laced disposition of the shoplifting trial. He permitted the witnesses to testify about the merits of the poem, but not whether they believed the poem was obscene. That would be his determination to make. He also permitted into evidence published reviews of the poem.

The case was the first to employ the new legal test for obscenity handed down by the Supreme Court in Roth v. United States that June. Roth required the challenged work be taken as a whole and sought to determine whether it had some redeeming social importance.

Roth's "utterly without redeeming value" test was a defense-friendly standard; the present-day formulation, taken from the Supreme Court's 1973 Miller v. California decision, asks a tougher question–whether it "lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value." Given the testimony of the defense's nine literary experts, it was not surprising that Judge Horn found Howl had value. "I conclude the book 'Howl and Other Poems' does have some redeeming social importance, and I find the book is not obscene."

My only cavil with the book's outstanding presentation of the Howl legal saga is the authors' attempt to refocus the narrative on Ferlinghetti's efforts to get the poem in print. While the details of his important contributions are welcome, the story was, and always will be, about the poem and its singular author, Allen Ginsberg–not the book's publisher. This isn't to detract from Ferlinghetti's bold decision to publish Howl–and his prescience to line up the ACLU to defend it. It is worth noting that included in the appendix is a transcript of his 2007 interview with Pacifica Radio to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the trial. Also worth a mention is that Ferlinghetti has just celebrated (in March) his 100th birthday!

The 2007 interview highlighted the paradoxical situation that Howl currently occupies. Freed from the ugly moniker "obscene," it is nevertheless still a censorship victim today. Not legally obscene, but merely "indecent," it can't be widely broadcast. Despite Judge Horn's decision, Howl can only be broadcast over the airwaves during late-night hours. Pacific radio and its flagship, WBAI, could not lightly ignore the threatened financial penalties that would be imposed by the FCC for a live broadcast. So instead of a live reading, Howl was simply posted on its website. This had not always been the case because Howl had often been broadcast over the airwaves in the years after Judge Horn's decision.

Following the Supreme Court's 1978 "indecency" decision, FCC v. Pacifica Radio, the FCC was emboldened to ramp up efforts to "clean-up" the airways. Ginsberg railed against the irony of increased censorship over the broadcast media, decades after the Howl obscenity battle had been won.

Since Ginsberg's 1997 death, Howl still cannot be broadcast outside the narrow late-night window for fear it could offend the sensibilities of children who might be listening. This is the ultimate irony because the FCC's justification is chillingly identical to that which was unsuccessfully proffered by the customs Inspector in 1957: "You wouldn't want your children to come across it."

Frank Colella is a clinical assistant professor at Pace University's Lubin School of Business. His law practice focuses on taxation, corporations and not-for-profit organizations.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

A Time for Action: Attorneys Must Answer MLK's Call to Defend Bar Associations and Stand for DEI Initiatives in 2025

4 minute read

The Public Is Best Served by an Ethics Commission That Is Not Dominated by the People It Oversees

4 minute read

The Crisis of Incarcerated Transgender People: A Call to Action for the Judiciary, Prosecutors, and Defense Counsel

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250