The Judge in Epstein's Case Should Not Turn the Dismissal Into a Drama for the Victims

Now that he is dead, the criminal justice system is not the place for Epstein to be called to account.

August 26, 2019 at 11:00 AM

6 minute read

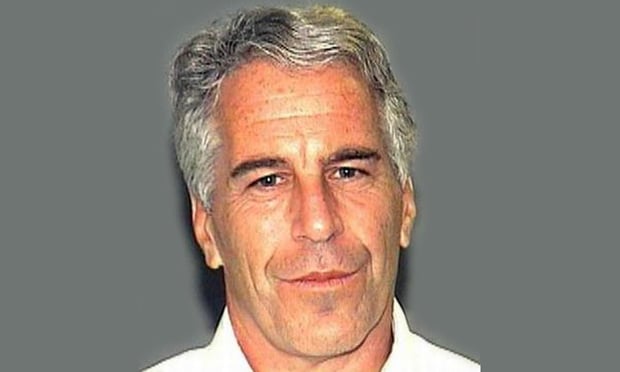

Jeffrey Epstein's 2011 police mug shot.

Jeffrey Epstein's 2011 police mug shot.

Last week, Judge Richard Berman ordered a hearing on the prosecutors' decision to dismiss the indictment against Jeffrey Epstein, who had been charged with multiple counts of sex trafficking and assault before he committed suicide in a Manhattan prison. The judge announced that he intends to allow victims to speak at the hearing, which is scheduled for August 27th. Berman stated: "The court believes that where, as here, a defendant has died before any judgment has been entered against him, the public may still have an informational interest in the process by which the prosecutor seeks dismissal of an indictment."

This is an odd moment for transparency in a criminal case. Normally, if a prosecutor seeks to dismiss an indictment for such an obviously worthy reason, the court would simply grant the request. The judge would not schedule a hearing and he definitely would not allow the victims to speak. And if he did hold a hearing, whatever informational interests the victims may have would be served by affording them a chance to attend the hearing, not by giving them a speaking role.

The procedural rules governing federal criminal cases do not provide for posthumous trials. If the accused dies before trial, the federal court has no choice but to dismiss the indictment and end the case. Indeed, if an accused is tried and found guilty but dies while his appeal is pending, the federal court must set the conviction aside, as if it had never occurred. If a party to a civil lawsuit dies, his estate may step into his shoes. But in a criminal prosecution, the defendant's estate cannot be asked to answer for the defendant's alleged crimes.

And so it is odd for the judge in this case to delay the inevitable dismissal, seemingly for dramatic effect. He has no choice but to dismiss the charges. At the hearing he scheduled, Epstein's lawyers will not oppose the prosecution's motion to dismiss the indictment. It is doubtful whether Epstein's former lawyers could oppose the prosecution's motion even if they thought there were grounds to do so. Epstein's defense lawyers no longer have authority to speak on his behalf: the lawyer-client relationship ended with his death. Nor would the victims have any plausible grounds to ask the judge to continue the proceedings.

People are right to be both outraged and frustrated after Epstein's suicide. He was a true villain, as both sides of the political divide agree: Epstein was hated by the #MeToo movement and conservatives alike. His suicide denied the public an accounting for his egregious crimes. It left us all without a clear sense of how this rich and powerful man evaded justice the first time, when he served a meager sentence, much of it on home arrest, for similar charges.

That said, now that he is dead, the criminal justice system is not the place for Epstein to be called to account. The fact that the public has an interest in learning more about the process, as Berman suggested, does not mean that victims have the right to speak at a criminal proceeding scheduled for no obvious purpose but to give them a forum. One might think that there is no harm done in giving victims a chance to express themselves in the scheduled hearing, but that is wrong for two reasons.

First, the criminal justice system is designed to determine whether defendants are guilty of alleged crimes beyond a reasonable doubt in a fair process in which both the prosecution and defendant participate. While many people assume that Epstein is guilty of the crimes alleged in the indictment and worse, our courts and constitution require that we presume him innocent until proven otherwise. Individuals charged with crimes must be allowed a chance to confront their accusers and put the government to its burden. Frustrating as it is that the government will never get the chance to present its case in a trial against Epstein, it is important to preserve the institutional structures nonetheless. Faith in the outcomes of run-of-the-mill cases require as much.

It is often important to hear from victims—for example, at a trial where the accused contests his guilt or in a sentencing hearing after a defendant is found guilty. But conducting a hearing on an uncontested question solely to give victims a chance to tell their stories would be a rare if not unprecedented use of the courtroom—one that not only veers from the norm but also weakens the institutional commitments that are necessary to ensure that all individuals accused of a crime are afforded proper protection.

Second, this seems more like a show than a real hearing. Judge Berman isn't really trying to obtain information about why the government is dismissing its case. We all know why. The defendant is no longer alive. So the hearing would necessarily be serving a different purpose: It might serve as a kind of theater at which the public works through its frustration and unresolved need for retribution. It might afford a collective catharsis for the victims who may be allowed to tell their stories in court and for other victims of sexual assault. These are both noble goals, but they are outside of the criminal justice system's mandate.

We don't necessarily have to give up the goal of a public accounting. Not entirely anyway. Prosecutors in the Southern District of New York have indicated that they are not done with the investigation, leaving many to speculate that Epstein's co-conspirators will be charged. If so, the victims will get to tell their stories, at least partially. In civil lawsuits and forfeiture actions, they may also have an opportunity for their day in court. But we should not distort the criminal justice process by importing this perceived societal need into the criminal courthouse when there is no proceeding in which hearing from the victims serves a legitimate criminal justice purpose.

Bruce Green is the Louis Stein Chair at Fordham Law School where he directs the Louis Stein Center for Professional Ethics. He formerly served as a federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York. Rebecca Roiphe is a professor of law at New York Law School, where she serves as the co-dean for faculty scholarship. She formerly served as an Assistant District Attorney in the New York County District Attorney's Office. Green submitted a legal ethics opinion in a defamation case pitting an alleged Epstein victim against lawyer Alan Dershowitz.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trending Stories

- 1Relaxing Penalties on Discovery Noncompliance Allows Criminal Cases to Get Decided on Merit

- 2Reviewing Judge Merchan's Unconditional Discharge

- 3With New Civil Jury Selection Rule, Litigants Should Carefully Weigh Waiver Risks

- 4Young Lawyers Become Old(er) Lawyers

- 5Caught In the In Between: A Legal Roadmap for the Sandwich Generation

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250