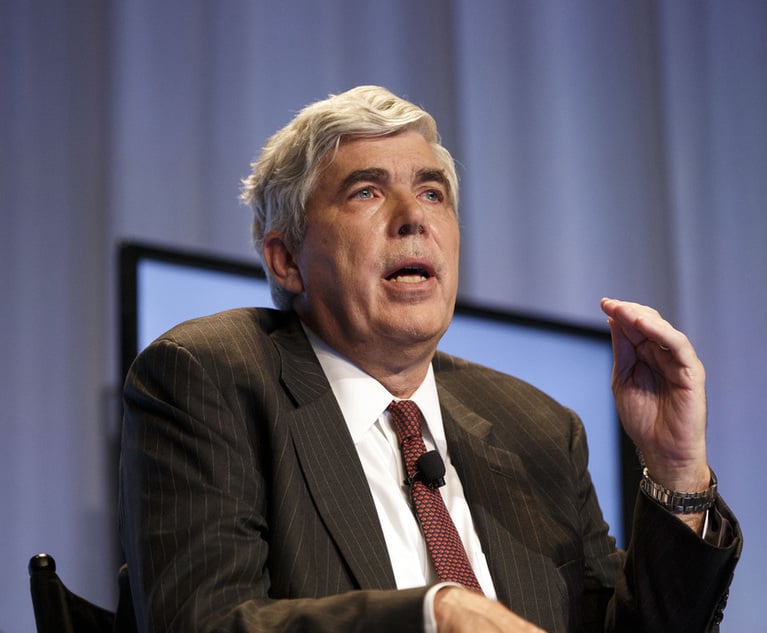

John C. Coffee Jr.

John C. Coffee Jr.Markopolos, G.E. and Short Selling as Negative Activism

In his Corporate Securities column, John C. Coffee Jr. writes: The recent campaign of Harry Markopolos and his allies in attacking General Electric's accounting is fascinating, challenging, and hard to evaluate, but clearly it demonstrates that we need to rethink the current legal treatment of short selling and "negative activism".

September 18, 2019 at 01:00 PM

11 minute read

The recent campaign of Harry Markopolos and his allies in attacking General Electric's accounting is fascinating, challenging, and hard to evaluate, but clearly it demonstrates that we need to rethink the current legal treatment of short selling and "negative activism". To briefly recap, Mr. Markopolos, who was, of course, the first to publicly proclaim that Bernie Madoff was running a giant Ponzi scheme, accused G.E. in August of being "A Bigger Fraud than Enron." Specifically, he produced a lengthy report (and an associated Power Point display designed to educate accounting-challenged journalists) that alleged a $38 billion accounting fraud at G.E. The key claims were that G.E. was "hiding $29 billion in Long-Term Care Losses" with respect to its insurance operations and was also concealing "$9.1 billion in Baker Hughes losses." See "General Electric, A Bigger Fraud Than Enron," www.gefraud.com (hereinafter, "GE Fraud").

When these disclosures hit the market in a well orchestrated blitz, G.E.'s stock price fell to a low of $7.76 per share on Aug. 15, 2019 (when over 400 million G.E. shares traded on that day). Overall, G.E.'s stock price dropped 21 percent throughout August (while the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell only 1.7 percent that month). Yet, in September 2019, G.E.'s stock price rebounded (after several peaks and valleys) and recovered most of August's losses, hitting a high of $9.40 at 1:00 p.m. on September 16 (as this column was completed). Does this prove or support G.E. CEO Lawrence Culp's charge that Mr. Markopolos's claims were "manipulation—pure and simple?" Not really. The stock price is still down over $1.00 per share since early August, and G.E. has decided to reduce its majority stake in Baker Hughes to a minority position (seemingly a partial concession of some of Mr. Markopolos's allegations).

But one aspect of Mr. Markopolos's campaign has attracted much notice and some concern. Mr. Markopolos disclosed that he had "entered into an agreement with a third-party entity to review an advance copy of the Report in return for later-provided compensation," which would be "based on a percentage of the profits resulting from the third-party entity's positions in" G.E. securities and derivatives. See GE Fraud at 2. At the same time his company, Forensic Decisions PR LLC, submitted their G.E. report to both the SEC's Whistleblower Program and a similar Department of Justice FIRREA Whistleblower Program. Finally, some individuals at his company (possibly including him) also shorted G.E.'s stock. In short, Mr. Markopolos was not simply a whistleblower, but a combined whistleblower/short seller who was also broadly giving investment advice to the public. Obviously, these incentives may bias him. Yet, his report was detailed and convincing to many. Beyond argument, Mr. Markopolos has demonstrated that, with his track record, he can gain attention (on a scale with Elvis). Thus, he is the paradigm of the new "negative activist".

Some academics have celebrated such short-selling activists as the "mirror image" of the "positive" hedge fund activist, who engages management and seeks to obtain representation on the board and force operational changes on the target company (usually, sales of divisions, stock buybacks, a merger, or a replacement of the CEO). As they see it, the negative activist is similarly forcing changes on the company, which will ultimately benefit shareholders (but possibly only after a long painful interim period during which the stock price sinks). See Barbara A. Bliss, Peter Molk and Frank Partnoy, "Negative Activism" (Feb. 25, 2019)). These authors argue that such "informational negative activism" should be "encouraged and even subsidized."

Shareholders, however, may be less pleased by the appearance of the negative activist (who sends prices downward) than by the appearance of a positive activist who usually causes a statistically significant price jump when it announces its presence by filing a Schedule 13D. Of course, shareholders cannot accuse Mr. Markopolos or his allies of insider trading, as he owes no fiduciary duty to them; he is neither an insider nor a tippee. There is a possibility, however, that Mr. Markopolos is acting as an unregistered investment advisor because he is providing investment advice for compensation (contingent compensation to be sure). Moreover, if the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 applies to him, it forbids (in §205) any investment advisory contract that "provides for compensation to the investment adviser on the basis of a share of capital gains upon or capital appreciation of the funds … of the client." Of course, this is exactly how the third-party client in this case has structured the compensation by offering Mr. Markopolos a percentage of its gains. Conceivably, Mr. Markopolos can claim an exemption from the Advisers Act (including for "Internet Investment Advisers" under Rule 203A-2), but no such claim is made in his report.

In any event, the more interesting question is whether one should be able to act in this joint capacity as a whistleblower, short seller and arguable investment adviser. Although some may argue that this was a "manipulation," the case law is clear that, unless Mr. Markopolos's report was false and misleading, merely taking a large short position is insufficient to establish manipulation. See ATSI Communications v. Skoar Fund, Ltd., 493 F.3d 87, at 101 (2d Cir. 2007). One can certainly disagree with Mr. Markopolos's analysis (and ultimately the market did by recovering most of its earlier losses), but strongly stated opinions are not fraudulent. Thus, if both insider trading and manipulation are non-starters, what is left? Section 17(b) of the 1933 Act is not violated here so long as the third party paying Mr. Markopolos and his firm is not a dealer. If the third party is a dealer, however, then there is a problem because §17(b) requires disclosures of the amount of consideration any dealer agreed to pay to Mr. Markopolos for his research (and that was not done here). Ironically, the intent of §17(b) is to prohibit undisclosed payments to stock promoters (and a short seller is the reverse), but the statutory language forbids any undisclosed payment for any communication that "describes such security."

Another conceivable possibility involves Omnicare v. Laborer's District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 135 S.Ct. 9318 (2015), which would impose liability if Mr. Markopolos's expressions of his opinion contain an "embedded" factual assertion that was materially false. For example, the public can reasonably assume that Mr. Markopolos does sincerely hold the view that G.E. is greatly overvalued by the market. Thus, if, having stated his view and profited from the downturn that he caused in G.E.'s stock, Mr. Markopolos were suddenly to reverse his position and buy stock in G.E. as G.E. was announcing its rebuttal, this might be inconsistent with Omnicare. My Columbia colleague, Prof. Joshua Mitts, who has studied short selling patterns closely, argues in a forthcoming article that even closing out one's short position without prior disclosure can be deceptive under this Omnicare gloss on a statement of an opinion. As he writes:

[T]he deception is inherent in the implication that, by recommending a stock for purchase or sale, and disclosing that the author holds an existing position in those shares which is consistent with that recommendation, the author is effectively stating that he or she does not intend to close that position—at least not in the short term.

See Joshua Mitts, "A Legal Perspective on Technology and the Capital Markets: Social Media, Short Activism and the Algorithmic Revolution" at p. 25 (2019). Perhaps, he is right, but the practical consequence of this position is that the short seller might have to maintain the short position for some undefined minimal period. While such a rule might be justifiable on policy grounds, I doubt that it is within the SEC's current power (absent new legislation). It is a prophylactic rule, rather than a disclosure rule.

What rule could be currently enforced? The SEC could make clear that a short seller who has published critical negative research and announced its short position must disclose immediately when it closes out its short position. That would inform the market that the short seller may no longer hold its prior position. This disclosure obligation would not be satisfied by a simple boilerplate statement by the short seller that it might, sometime in the future close out its short position.

Some Second Circuit decisions arguably support this need for immediate disclosure on the closing of the short position. For example, in In re Time Warner Inc. Securities Litigation, 9 F. 3d 259, 267 (2d Cir. 1993), the Second Circuit found that a "duty to update opinions and projections may arise if the original opinions or projections have become misleading as the result of intervening events." A public expression that the company is a "worse fraud than Enron" is seemingly undercut when one closes out one's short position just as the issuer is responding.

If one views the short seller as a hero (as the proponents of "negative activism appear to), this may seem overly harsh. But let's return here to the actual facts of Mr. Markopolos's engagement with G.E. The stock went way down on Mr. Markopolos's attack and then largely rebounded. Thus, at least as of this point, he has not identified a new Enron. But he and his allies could profit almost as much as if they had hit pay dirt. To my mind, the real problem here is that he has imposed great volatility on the market without ultimately proving his case. Worse yet, this is a virtually riskless activity that he and his allies can exploit even if they expect that the issuer will be able to respond effectively. That is, a prominent short seller can expect that a credible, carefully argued attack will drive the market down, and Mr. Markopolos used dramatic, even lurid, prose in comparing G.E. with Enron. Even if the short seller recognizes that the issuer can respond credibly, the short seller can exploit a nearly inevitable timing gap (even if only a day or so) between its attack and the issuer's response. Remember that over 400 million G.E. shares traded on Aug. 15, 2015 (the day that the Markopolos report was released). The ability to exploit this timing gap (and close your short position before the issuer responds) creates an incentive to overstate (and Mr. Markopolos may have done so, at least in tone). Ultimately, we want to reward the short seller who uncovers a fraud (as Jim Chanos did at Enron), but not one who simply causes a wild market swing with little or no net price movement. If short sellers can profit in this fashion, we can expect a much more volatile market with roller coaster-like price swings.

If legislation were to be considered, one possibility (which some have proposed) would be to create a mirror image to §13(d) of the Securities Exchange Act so that a short seller (or a short seller "group") had an obligation to disclose promptly after assembling a short position of some size (say, 2 percent of the class, because a 5 percent short position is rare). This would also require disclosure of the terms within the "group" and the fees to be paid.

Stronger measures can be imagined, including a parallel to §16(b) of the Securities Exchange Act for truly large short sellers. But frankly, the problem has not yet been shown to require that drastic a remedy.

One last point about the Mr. Markopolos attempt to combine whistleblowing and short selling. Under the statute, there is no inherent problem with this combination, but Mr. Markopolos filed his claim with the SEC on behalf of his company (Forensic Decisions PR LLC). Both the statute (§21F(a)(6) of the Securities Exchange Act) and the SEC's rules (Rule 21F-2(a)(1)) require that a whistleblower be an individual. A whistleblower award may not be important to Mr. Markopolos, as the gains to a short seller should exceed any likely whistleblower award (and the prospect that the SEC will sue GE is modest at best).

The roles of whistleblower, short seller, and de facto investment adviser do not combine seamlessly. Thus, it will be interesting to watch how the SEC reacts, if it does at all. At present, the only legal rules that truly bind the negative activist are Regulation SHO (which prohibits "naked" short selling and no evidence is available that this occurred here) and an "alternative uptick" rule (which may have applied here, but only after the stock price fell over 10 percent relative to the prior day's closing trading price). If there is an SEC rule that may need renewed consideration, it would be an uptick rule that would cut in at an earlier point. This column seeks only to raise a possibility, not conduct a thorough analysis.

John C. Coffee Jr. is the Adolf A. Berle Professor of Law at Columbia University Law School and Director of its Center on Corporate Governance.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Trump Mulls Big Changes to Banking Regulation, Unsettling the Industry

Trump's SEC Overhaul: What It Means for Big Law Capital Markets, Crypto Work

Trending Stories

- 1Biggest Legal Tech People Moves of 2024

- 2NY Civil Liberties Legal Director Stepping Down After Lengthy Tenure

- 3Preparing for 2025: Anticipated Policy Changes Affecting U.S. Businesses Under the Trump Administration

- 4High Court May Limit the Reach of the Wire Fraud Statute

- 5Nelson Mullins Doubles Partner Promotions for 2025

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250