Andy Warhol's 'Prince Series' Works Held To Make Fair Use of Prince Photograph

On July 1, 2019, the U.S. District Court Judge John Koetl for the Southern District of New York held that a series of silkscreen paintings and prints by Andy Warhol based on a photograph of the rock star Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith constituted a transformative and fair use. In their Copyright Law column, Robert J. Bernstein and Robert W. Clarida discuss the decision, which will be appealed to the Second Circuit.

September 19, 2019 at 12:30 PM

11 minute read

Robert J. Bernstein and Robert W. Clarida

Robert J. Bernstein and Robert W. Clarida

On July 1, 2019, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, in an Opinion and Order by Judge John J. Koetl, held that a series of silkscreen paintings and prints by Andy Warhol based on a photograph of the rock star Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith constituted a transformative and fair use. The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312 (S.D.N.Y. 2019) (Warhol Foundation). In so holding, Judge Koetl relied on a 2013 Second Circuit decision holding that an "appropriation artist," Richard Prince (no relation to the rock star), made a transformative and fair use of photographs taken by Patrick Cariou. Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013) (Cariou). Cariou has been criticized for its characterization of the changes made by Richard Prince as transformative, a criticism that Goldsmith no doubt will be making in her pending appeal of Judge Koetl's decision.

Facts

Lynn Goldsmith has long been recognized as a leading photographer of rock, jazz and R&B performers. In 1981, she took a number of studio photographs of Prince on assignment from Newsweek Magazine. In 1984, Goldsmith licensed Vanity Fair Magazine to use one of those photographs (the Goldsmith Prince Photograph) in an article for an artist's reference. Goldsmith's photography agency submitted the Goldsmith Photograph to Vanity Fair, a Condé Nast publication, which in turn commissioned Andy Warhol to create an illustration of Prince for an article entitled "Purple Fame" that appeared in the November 1984 issue of Vanity Fair (the Purple Fame article). Warhol used the photograph in creating a series of 16 works, comprised of 12 silkscreen paintings, two screen prints on paper, and two drawings (the Prince Series works). One of the Prince Series works appeared in the Purple Fame article, described as "a special portrait for Vanity Fair by ANDY WARHOL," along with a copyright reference as follows: "source photograph © 1984 by Lynn Goldsmith/LGI." After Warhol died in 1987, ownership of the Prince Series works passed from Warhol's Estate to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF). The Prince Series works have since been published widely and displayed in museums and other public places on numerous occasions pursuant to licenses from AWF.

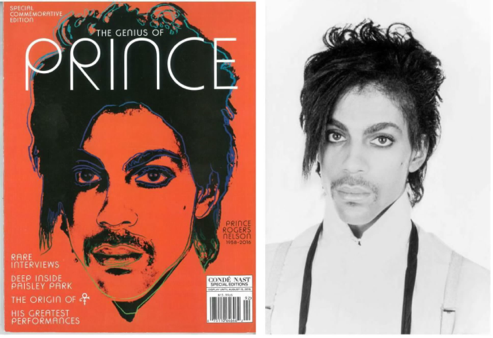

Upon Prince's death in April 2016, Vanity Fair published an online version of the Purple Fame article, including Warhol's illustration of Prince, crediting both Warhol and Goldsmith for the illustration. Soon thereafter, Condé Nast issued a commemorative magazine, "The Genius of Prince," using as its cover illustration another one of the Prince Series works (the Condé Nast Warhol Prince illustration), pursuant to license from AWF, this time with a copyright credit to Warhol but not to Goldsmith. Goldsmith claimed that she first became aware of Warhol's use of her photograph in creating the Prince Series works upon seeing the Condé Nast Warhol Prince illustration in 2016. Soon thereafter, Goldsmith notified Condé Nast of her infringement claim and obtained a copyright registration for her photograph.

AWF then brought a declaratory judgment action seeking declarations that (1) the Warhol Prince Series works did not infringe the Goldsmith Prince Photograph, and (2) in any event, any use of the Goldsmith Prince Photograph in the Warhol Prince Series works constituted fair use. Goldsmith counterclaimed asserting copyright infringement. The Condé Nast Warhol Prince illustration and the Goldsmith Prince Photograph are set forth below as reproduced in the opinion.

Although in his fair use analysis Judge Koetl primarily referenced these two works, he considered that analysis to apply as well to the entire series of 16 works in Warhol's Prince Series.

District Court Opinion

Before considering fair use, Judge Koetl addressed AWF's arguments that Goldsmith's claim was barred by the three-year statute of limitations set forth in §507(b) of the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §507(b), and that the Warhol Prince illustration did not infringe the Goldsmith Prince Photograph because the two works were not "substantially similar." On the statute of limitations, the court found that Condé Nast's 2016 publication of the Prince Commemorative Magazine was a new infringement within the three-year period. Moreover, the statute of limitations would not bar infringement claims as to ongoing and future licensing of the Warhol Prince Series works by AWF. Because Goldsmith sought no relief as to the 1984 Vanity Fair publication, Judge Koetl did not address whether her claimed discovery of that publication within three years preceding her counterclaim for infringement avoided the limitations bar as to that use.

With respect to infringement, the court first noted that AWF did not deny, for the purpose of the summary judgment motions only, "that there was access and sufficient probative similarity to establish that Warhol 'copied' the Goldsmith Prince Photograph—at least to some extent." Warhol Foundation, 382 F. Supp. 3d at 323. However, to establish infringement it is also necessary to establish "unlawful appropriation," i.e., "that substantial similarities as to the protected elements of the work would cause an average lay observer to recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the copyrighted work." Id. at 323 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). AWF denied that any similarities were sufficient to constitute infringement. Judge Koetl declined to opine on that issue because he considered it to be "plain that the Prince Series works are protected by fair use … . a statutory exception to copyright infringement." Id. at 324.

At the outset of his fair use analysis, Judge Koetl observed that the "critical question in determining fair use is whether copyright law's goal of 'promot[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts would be better served by allowing the use than by preventing it.'" Id. (citing Castle Rock Entm't v. Carol Pub. Grp., 150 F.3d 132, 141 (2d Cir. 1998)). We note, however, that this overarching inquiry, which apparently guided the court's consideration of each of the fair use factors and their overall balance, is inherently subjective, and may not be so "plain" to the appellate panel.

The fair use factors are set forth in §107 of the Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §107, which provides, inter alia:

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work … for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, … scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

• the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

• the nature of the copyrighted work;

• the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

• the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

On the first factor, the court noted that the most important inquiry is whether the use is "transformative," i.e., "'whether the new work merely supersede[s] the objects of the original creation or instead adds something new, with a further purpose of different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.'" Warhol Foundation, 382 F. Supp. 3d at 325 (quoting Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 U.S. 569, 579 (1994)). Judge Koetl found that Warhol's Prince Series works were transformative because they alter the Goldsmith Prince Photograph in a manner resulting "in an aesthetic and character different from the original" and "add something new to the world of art," and that "the public would be deprived of this contribution if the works could not be distributed." Id. at 326. The court did not consider the possibility that injunctive relief might not necessarily follow from a holding of infringement.

Judge Koetl described Warhol's "transformation" of the Goldsmith photograph as follows:

The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure. The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith's photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a "Warhol" rather than as a photograph of Prince … .

Id.

He therefore weighed the first factor strongly in favor of AWF.

The court found that the second fair use factor (the nature of the copyrighted work) favored neither party because, although the creative nature of photographs generally balances this factor in favor of the photographer, the transformative nature of the Prince Series works rendered this factor "of limited importance." Id. at 327 (citing Cariou, 714 F.3d at 710).

On the third factor, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, the court observed that "the extent of permissible copying varies with the purpose and character of the use." Id. at 327 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). Relying on Cariou, the court found this factor weighed heavily in AWF's favor because although key portions (Prince's head and neckline) of the Goldsmith photograph were used, "Warhol removed nearly all the photograph's protectable elements" and "transformed Goldsmith's work into something new and different." Id. at 329-30 (citing Cariou, 714 F.3d at 710). The court identified Prince's facial features and his pose as non-protectable elements in the Goldsmith photograph.

On the fourth factor, the court observed that the inquiry into the effect of the use on the potential market (including the market for derivative works) focuses on whether the secondary use usurps the market for the original work by providing a substitute for the original, and that "[t]he more transformative the secondary use, the less likelihood that the secondary use substitutes for the original." Warhol Foundation, 382 F.3d at 330 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). Goldsmith contended that her licensing markets were adversely affected by the use. However, the court found that Goldsmith provided "no reason to conclude that potential licensees will view Warhol's Prince Series, consisting of stylized works manifesting a uniquely Warhol aesthetic, as a substitute for her intimate and realistic photograph of Prince." Id. at 330-31. The court therefore weighed the fourth factor in AWF's favor.

Having found the first factor weighing strongly in AWF's favor, the second factor neutral, the third factor weighing heavily in AWF's favor, and the fourth factor favoring AWF, the court concluded that the overall balancing of the fair use factors "points decidedly in favor of AWF." The court therefore held that the Prince Series works are protected by fair use and dismissed Goldsmith's copyright infringement claim.

Conclusion

Whether this resolution better serves "copyright law's goal of 'promot[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts"—the critical fair use inquiry identified by Judge Koetl at the outset of his analysis—will next be addressed by the Second Circuit. The scope of protection afforded to the art of photography, and the leeway given to an artist making use of a photograph in creating a painting or illustration, impact the progress of both forms of creative expression. Moreover, a determination of infringement does not necessarily result in injunctive relief, which is discretionary and itself subject to multi-factor analysis (eBay v. MercExchange, 547 U.S. 388 (2006)), whereas a holding of fair use deprives the photographer of any compensation for the use. A notice of appeal was filed on Aug. 7, 2019 (Docket No. 19-2420).

Robert J. Bernstein practices law in The Law Office of Robert J. Bernstein and is a past President of the Copyright Society of the U. S.A. Robert W. Clarida is a partner at Reitler, Kailas & Rosenblatt and the author of the treatise Copyright Law Deskbook (BNA).

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

‘Second’ Time’s a Charm? The Second Circuit Reaffirms the Contours of the Special Interest Beneficiary Standing Rule

Attorney Fee Reimbursement for Non-Party Subpoena Recipients Under CPLR 3122(d)

6 minute read

Here’s Looking at You, Starwood: A Piercing the Corporate Veil Story?

7 minute readTrending Stories

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250