Is There a Duty to Cross-Examine a Witness Statement?

In their International Arbitration column, Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky discuss the recent case 'P v. D' where the English High Court set aside an international arbitration award because of the failure of the successful party's counsel to conduct the kind of cross-examination required by Browne v. Dunn. Evidently, the arbitration proceeding, which took place in England, was not conducted in accordance with the IBA Rules.

September 25, 2019 at 11:00 AM

9 minute read

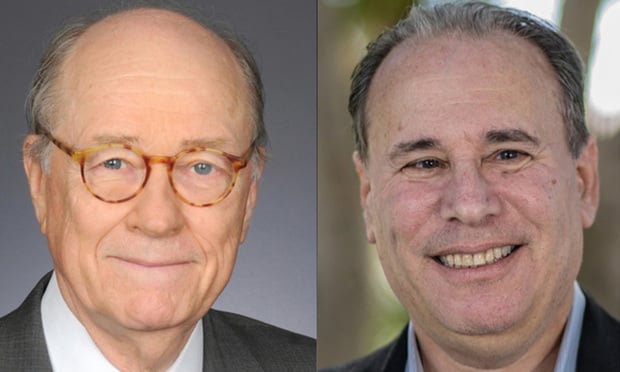

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

International arbitration hearings are primarily about cross-examination. Direct testimony, both from fact witnesses and experts, almost always comes from written statements or reports presented by the witnesses. As we discussed in two columns several years ago, cross-examination of witnesses proffering written statements can involve strategic or tactical decisions, including whether to cross-examine at all. See "Cross-examination in International Arbitration," NYLJ (March 26, 2007), and "Witness Statements in International Arbitration," NYLJ (May 27, 2008).

Under English law, going back to the 1894 case of Browne v. Dunn [1894] 6 R 57, a House of Lords case, arguments may be made to a court or jury only if the witness has been confronted in error with the challenge to his or her credibility that testimony of a witness is not credible. That is, the court practice has been that, if a party challenging the evidence of a witness failed to make it plain to the witness, that his or her evidence was not accepted, the judge would have to comment to the jury that one party's case had not been put, even though the two cases were diametrically opposed. The underlying rationale appears to be a Victorian one—that it is unfair to argue to a court that the testimony of a witness is not to be believed unless the witness has been given the opportunity to respond to the "imputation" of dishonesty.

This English rule, although it can still be seen in English court procedure, is virtually unheard of in international arbitration proceedings, since they are generally conducted in accordance with the practices described in the IBA Rules on the Taking of Evidence in International Arbitration. Article 4.8 thereof provides that "if the appearance of a witness has not been requested pursuant to Article 8.1, none of the other parties shall have been deemed to have agreed to the correctness of the witness statement." English arbitration law, embodied in the 1996 Arbitration Act, permits the arbitral tribunal to "decide all procedural and evidential matters, including 'whether any and if so what questions should be put to and answered by the respective parties and when and in what form this should be done.'" Article 34(2)(e).

'P v. D'

In a recent case (P v. D [2019] EWHC 1277 (Comm)), however, the English High Court set aside an international arbitration award because of the failure of the successful party's counsel to conduct the kind of cross-examination required by Browne v. Dunn. Evidently, the arbitration proceeding, which took place in England, was not conducted in accordance with the IBA Rules.

In the arbitration hearing, the core issue was whether there was an agreement between Company P and Company D under which the repayment of Company D's loan to Company P, which involved hundreds of millions of dollars, would be extended until January 2020. Company P alleged that an oral agreement had been made in a meeting participated in by Mr. E of Company P and Mr. D of Company D on Mr. D's yacht in August 2015. Mr. D denied in his witness statement that any such meeting had taken place and stated that no such agreement had been made. Mr. E, on the other hand, in his witness statement, described the meeting and what he said was agreed to concerning the extension of repayment of the loan until January 2020.

In the hearing, counsel for Company D, Mr. Berry, cross-examined Mr. E for some two days, but did not deal directly in his questioning with the yacht meeting said to have been held in August 2015. The closest Mr. Berry came to questioning Mr. E on the meeting was a question he put to Mr. E regarding the meeting. "That's complete nonsense, Mr. E, isn't it?" Mr. E responded, "No, you're wrong." Mr. Berry then asked Mr. E why Mr. D would "countenance an extension to a loan you haven't even paid and you won't pay?" Mr. E responded that Mr. D would do so because he was an investor in the company and that it was clear to Mr. D that the extended time frame would be required to realize a return on his investment.

Mr. D, when cross-examined, was belligerent and obstructive and not believed by the tribunal. Nonetheless, the tribunal was not persuaded that there was an agreement made in an August 2015 meeting, evidently relying on the lack of any written confirmation of the alleged agreement.

The unsuccessful party, referred to in the decision as "Company P," sought relief under Section 68 of the Arbitration Act, which provides that a party to arbitral proceedings may apply to the court to have an arbitral award set aside on the ground of "serious irregularity affecting the tribunal, the proceedings or the award." One of the "serious irregularities" referred to in Section 68(2)(a) is the "failure by the tribunal to comply with Section 33 (general duty of tribunal)," which section provides that the tribunal shall "act fairly and impartially as between the parties, giving each party a reasonable opportunity of putting its case and dealing with that of his opponent…." Section 33(1)(a).

The court, in discussing the record of the arbitration proceedings, described what had occurred with respect to the examination of Mr. E as an "irregularity of procedure" because of the failure of the tribunal to give Company P, in the language of Section 33 of the Arbitration Act, "a reasonable opportunity of putting his case and dealing with that of his opponent." That is, since Mr. Berry failed to cross-examine Mr. E on the statements he made in his written statement concerning the alleged extension agreement with Company D, Company P argued that Company D could not contend that Mr. E's testimony concerning the existence and alleged content of the August 2015 agreement should not be believed because, notwithstanding Mr. E's detailed witness statement regarding the alleged meeting, opposing counsel did not contend to his face that what Mr. E said in his witness statement was not true.

The court referred to numerous English cases, including Vee Networks v. Econet Wireless International Ltd [2005] 1 Lloyd's Law Rep 192, paragraph 90, in which the court said, "… where there has been an irregularity of procedure, it is enough if it is shown that it caused the arbitrator to reach a conclusion unfavorable to the applicant which, but for the irregularity, he might well never have reached, provided always that the opposite conclusion is at least reasonably arguable." Thus, the court set aside the award based on what appears to have been the possibility that Mr. E might have somehow acquitted himself so well in a "properly" conducted cross-examination that his evidence in his written statement might have been accepted notwithstanding the lack of any written substantiation of that testimony.

The court conceded that the position in which the tribunal had found itself as a result of the failure to cross-examine was not "easy," where, despite what the court called "clear indications" to counsel for Company D, he did not cross-examine Mr. E on the alleged meeting. The court did not say what the arbitrators could or should have done to remedy the situation, even though, under Section 34, "it shall be for the tribunal to decide all procedural and evidential matters including questioning." One can understand why the counsel for Company D might have chosen not to cross-examine on the subject of the August 2015 meeting: counsel evidently thought that he would not gain anything and might lose by the answers to questions that he might put.

The court, in allowing the application of Section 68, stated that it was satisfied that there had been a breach of Section 33, observing, "I cannot possibly say that if Mr. E had been properly cross-examined and given the opportunity to deal with what were in the event seen as weaknesses by the arbitrators in this case… there might not have been a different outcome." Opinion, paragraph 39.

The court's decision also makes no mention of what one might say regarding the evidence offered by Mr. E on behalf of Company P: whether there had been an oral extension agreement was a matter of burden of proof of which the credibility of Mr. E was a component. Company P had the burden of persuading the arbitrators that such an agreement had been made and it failed because it offered no more than a detailed description of the meeting and its content but no corroboration by other witnesses or any writings. One may wonder why there should have been an obligation on the part of a lawyer for the opposing party to question the witness in such a way as to add oral evidence to the possible detriment of his client's case. Or why the party submitting a witness statement had a right to expect—as the court put it, a "proper" cross-examination—of the contents of that witness statement.

Conclusion

The opinion also reflects the opportunities that courts have, under Section 68 of the English Arbitration Act, to delve into the process by which a tribunal arrived at its award in determining whether there were "serious irregularities" in the arbitration proceedings. The decision also can be regarded as a cautionary example of what can happen in arbitrations sited in England & Wales in which provision has not been made by the parties or arbitrators regarding how the proceedings are to be conducted as far as the hearings are concerned.

Lawrence W. Newman is of counsel and David Zaslowsky is a partner in the New York office of Baker McKenzie. They can be reached at [email protected] and david.zaslowsky@bakermckenzie.com, respectively.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Serious Legal Errors'?: Rival League May Appeal Following Dismissal of Soccer Antitrust Case

6 minute read

How Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Thursday Newspaper

- 2Public Notices/Calendars

- 3Judicial Ethics Opinion 24-117

- 4Rejuvenation of a Sharp Employer Non-Compete Tool: Delaware Supreme Court Reinvigorates the Employee Choice Doctrine

- 5Mastering Litigation in New York’s Commercial Division Part V, Leave It to the Experts: Expert Discovery in the New York Commercial Division

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250