CEO Pay Growth Versus Total Shareholder Return

In his Executive Compensation column, Joseph E. Bachelder III takes a look at the growth rate of CEO pay and TSR over the five-year period 2014-2018 for the following groups: (i) the S&P 500 companies and (ii) large companies in three industries: commercial banking, retail sales and computer software.

September 26, 2019 at 11:00 AM

8 minute read

Joseph E. Bachelder III

Joseph E. Bachelder III

One of the methodologies used to assess the reasonableness of CEO pay is a comparison of the growth rate in CEO pay with the company's total shareholder return (TSR) over a period of time. TSR generally represents (a) the change in stock price of the company over the period of time being measured plus dividends paid during such period divided by (b) the stock price at the beginning of the period. In 2015 the SEC proposed a new rule that would require each issuer to disclose in its proxy statements over a period of five years (initially, over three years) (a) the levels of CEO pay (as well as that of the other NEOs) and (b) the TSR of the issuer (as well as the TSR of a peer group of companies). See Pay Versus Performance, SEC Release No. 34-74835; File No. S7-07-15 (April 29, 2015), 80 Fed. Reg. 26329 (May 7, 2015).

Today's column takes a look at the growth rate of CEO pay and TSR over the five-year period 2014-2018 for the following groups: (i) the S&P 500 companies and (ii) large companies in three industries: commercial banking, retail sales and computer software.

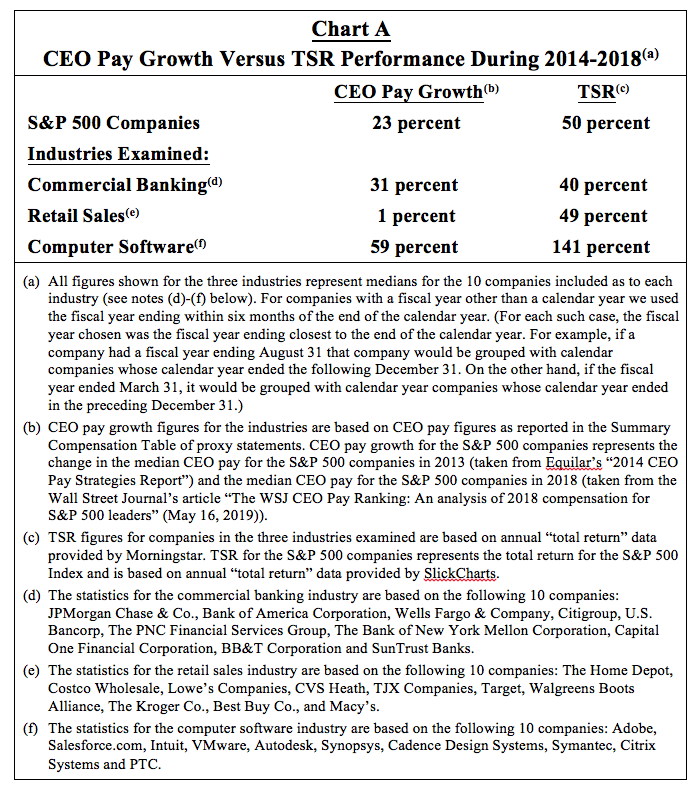

Chart A shows the growth rate of CEO pay and TSR for each of the groups as noted.

Chart A shows that the growth rate of CEO pay for the five-year period 2014-2018 trails the TSR for that period. The five-year growth rate in CEO pay for the S&P 500 companies is 23 percent compared with the five-year TSR for the S&P 500 companies of 50 percent. In each of the three industries examined CEO pay growth likewise trails TSR for the five-year period 2014-2018.

Examining the Alignment of CEO Pay Growth and TSR Performance. We examined the alignment (correlation) of CEO pay growth and TSR during the five-year period 2014-2018 for each of the 10 companies in each of the three industries. We did this as follows:

First, we ranked CEO pay growth over the five-year period for each of the 10 companies in each of the three industries. (A "1" represented the lowest growth and a "10" represented the highest growth.)

Second, we ranked TSR over the five-year period for each of the 10 companies in each of the three industries. (Again, ranking was on a scale of "1" (the lowest TSR) to "10" (highest TSR).)

Third, and last, for each of the 10 companies in each industry, we compared its ranking (1 to 10) in CEO pay growth over the five-year period to its ranking (1 to 10) in TSR over the five-year period.

After the third step, we calculated the difference for each company between its ranking in the industry for the five-year period for (i) CEO pay growth and (ii) TSR (in each case, a number between 1 and 10).

To illustrate, if a company's ranking in the industry was number 4 in CEO pay growth and number 4 in TSR there would be "perfect" correlation between that company's CEO pay growth and its TSR relative to the other nine companies in the industry. On the other hand, if the company in question was number 2 in CEO pay growth and number 9 in TSR, a difference of 7, there would be poor alignment. (The same conclusion as to poor alignment would apply if the reverse occurred: a ranking of number 9 in CEO pay growth and a ranking of number 2 in TSR.)

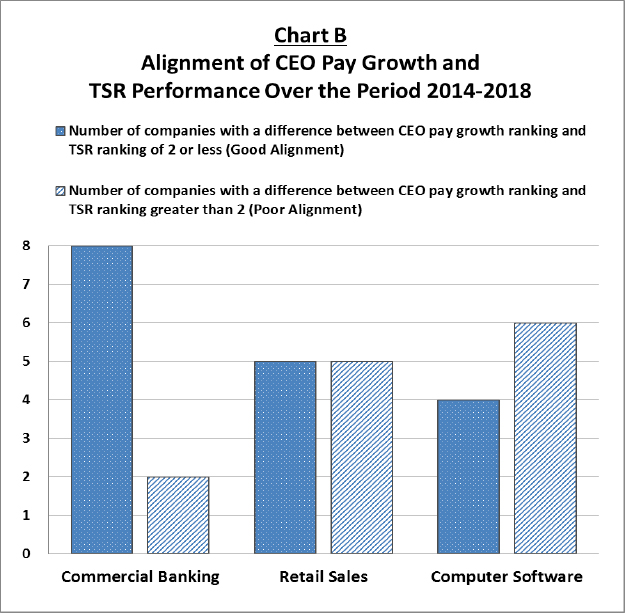

Chart B compares the CEO pay growth rankings and TSR rankings, as discussed, for the 10 companies in each of the three industries. As noted in the chart, we defined good alignment as a difference of 2 "points" or less between the ranking of a company in its industry in CEO pay growth and its ranking in TSR.

Chart B shows that, for the companies examined in the commercial banking industry, 80 percent (eight out of 10) have a good alignment (as we defined it) of CEO pay growth and TSR performance, compared to 50 percent and 40 percent for the retail sales industry and computer software industry, respectively.

There are numerous factors that contribute to the alignment of CEO pay growth with TSR performance and numerous factors that can cause misalignment. Factors that contribute to the alignment of CEO pay growth with TSR performance are as follows:

(a) In making CEO pay decisions each company (meaning the Board of Directors and/or the Compensation Committee of the Board) takes a look at that company's pay and performance and compares that pay and performance with the pay and performance of companies it considers "peer" companies. In the process of making those comparisons the company necessarily makes its decision as to the CEO's pay in the context of TSR performance (as well as other measures of company performance including operating performance).

(b) Employers (again, meaning Boards and/or Compensation Committees) have available to them data showing what peer companies are paying and how those companies are performing relative to their own company.

(c) In addressing the pay of its CEO a company must take into account the competitive market for CEO talent which, in most cases, reflects the relative performance of the companies in that market. (The meaningfulness of comparing CEO pay among companies will be lessened to the extent the companies in question are in different industries.)

In contrast to factors contributing to alignment as just noted, there are numerous factors that work against the alignment of CEO pay growth with TSR performance.

(a) A new CEO may have been hired during the time period being examined (e.g., the most recent five years). The new CEO's compensation likely will not represent the same change in pay that would have applied to a CEO continuing in the position. Different factors are taken into account with a new CEO including the "price" it takes, in many cases, to get the CEO candidate to leave his or her current employer and join the company in question.

(b) The performance of a CEO during the time period being examined may not yet have fully impacted the TSR for that period. (The impact of the CEO's service (positive or negative) may not be felt for some time—in some cases years—after the CEO has stepped down as CEO.)

(c) During the time period being examined the CEO may receive significantly more (or significantly less) pay, on an annualized basis, than he received (i) in the "base year" or (ii) in the last year of the period. In fact, these are the only two years being compared in most commentary on growth in CEO pay over a particular time period.

(d) The CEO may have received awards before the beginning of the time period being examined that do not reflect the performance, as it turns out, for that period.

(e) A CEO already may have a significant equity interest in the company (e.g., a family inheritance or founder equity). Does such an executive need to have additional equity to be sufficiently motivated to perform well?

(f) TSR may be influenced by factors outside the control of the CEO (and hence not reflected in the compensation of the CEO during the period in question).

Summary

(1) CEO pay growth, at most public companies, is not closely correlated with TSR performance. (The rule proposed by the SEC in 2015 in SEC Release No. 34-74835, noted at the outset of the column, has not been adopted.)

(2) Over the 2014-2018 period, at S&P 500 companies and at the companies in the three industries examined, the median CEO pay growth trailed TSR performance (as shown in Chart A).

(3) CEO pay decisions at most public companies reflect a variety of facts and circumstances that go beyond TSR performance.

Joseph E. Bachelder III is special counsel to McCarter & English. Andy Tsang, a senior financial analyst with the firm, assisted in the preparation of this column.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'A Shock to the System’: Some Government Attorneys Are Forced Out, While Others Weigh Job Options

7 minute read

'Serious Legal Errors'?: Rival League May Appeal Following Dismissal of Soccer Antitrust Case

6 minute read

How Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

4 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1Recent Controversial Decision and Insurance Law May Mitigate Exposure for Companies Subject to False Claims Act Lawsuits

- 2Visa Revocation and Removal: Can the New Administration Remove Foreign Nationals for Past Advocacy?

- 3Your Communications Are Not Secure! What Legal Professionals Need to Know

- 4Legal Leaders Need To Create A High-Trust Culture

- 5There's a New Chief Judge in Town: Meet the Top Miami Jurist

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250