Lifetime Achievement Award: Michael Cooper

It has been a lifetime of achievement, in keeping with the name of the award, but Michael has not lost his zeal.

October 18, 2019 at 11:09 AM

4 minute read

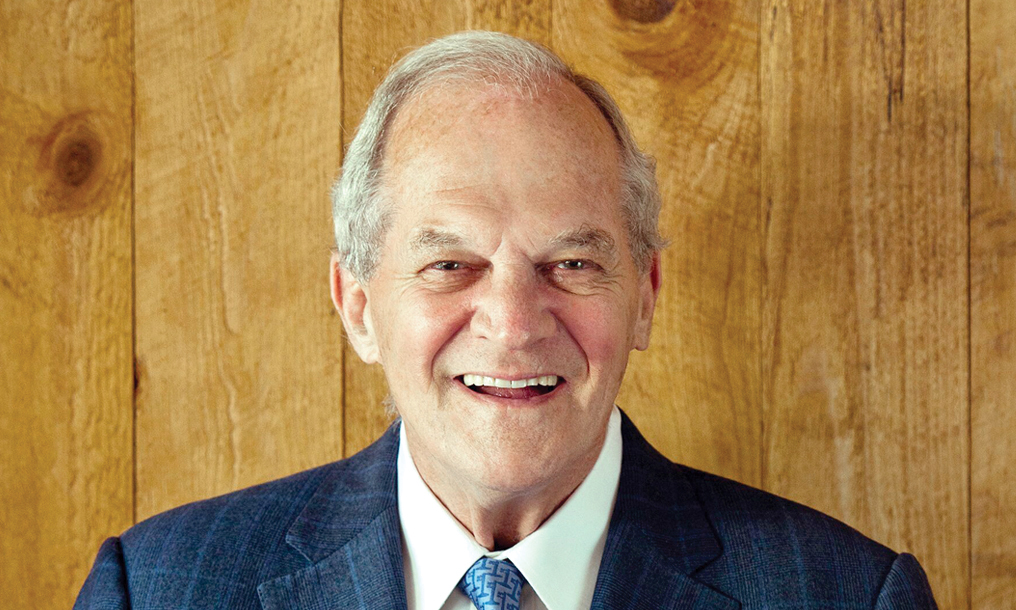

Michael Cooper, of counsel, Sullivan & Cromwell (courtesy photo)

Michael Cooper, of counsel, Sullivan & Cromwell (courtesy photo)

It is called the Lifetime Achievement Award. Some observers might take this to mean that the honoree has concluded a lifetime of doing very good things, and is now ready to sit back in contented repose. That is not what is going on here. We still expect a lot more of Michael Cooper, we really do.

He is responsible for this state of affairs, for unfailingly stepping up for the Good Cause, and so we have come to expect it of him. Wisely, the New York Law Journal has based the award on one's "impact on the legal community and the practice of law." The standard is not what the honoree has done to win fame, but what the honoree has done for others: the legal community and, in turn, the larger community.

As a prominent lawyer, Michael shines. He was managing partner of Sullivan & Cromwell's litigation group from 1978 to 1985. His eminence as a practitioner in commercial litigation, shareholder derivative suits, antitrust, securities, banking law and related fields is unsurpassed. When the Firm has needed advice on ethics it has called on him.

Michael's reputation is national, and for good reason. He served on the American Bar Association Task Force on Civil Trial Practice Standards. He was a Trustee of the Federal Bar Council, and President of the American College of Trial Lawyers after serving as a regent.

But the light shines brighter still because Michael, the ultimate lawyer, has made time to take on leadership roles in ways that advanced the lives of others—often those most in need. He helped found the Lawyers Assistance Program, which aided lawyers beset by alcohol, drugs, or other addictions, and has served more than 4,000 people. He was co-chair of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, an activity that grew out of his duration as President of the New York Legal Aid Society. He chaired a task force of the New York City Bar Association, studying ways to help ex-offenders get jobs and become productive.

Disclosure: I've known Michael for over 60 years, as law school classmates. I officiated at the wedding of his son, Jeffrey, a renowned law professor. Added disclosure: My wife Julie and I are also fans of Mike's talented wife, Nan, and so I may carry a bias. Still, I marvel at how he could excel in big-time lawsuits at one moment and, in the next, look after the impoverished or work to release someone from Guantanamo as part of his pro bono universe

Judith Kaye, our late beloved Chief Judge, also thought the world of Michael. We might be discussing some issue vexing the profession, and as often as not, Judith would exclaim: "I have a great idea. Let's call Mike Cooper!"

Around the time that Michael was President of the City Bar, it sponsored the final rounds of a nationwide law school moot court competition. We served together as judges on a three-member bench in the Great Hall on the second floor—you know, the room with the bright red carpet and the elegant black chairs, an apt setting (where from his picture on the wall he now greets us). It was as though he grew up on the woolsack, asking the orators questions, as courteous as they were astute. Michael would have made a very good judge.

Mystery writers speak of someone living a double life. This usually means that one, if not both lives, were bad. The phrase smacks of duplicity. Might I propose another coinage? A double life, both lived with integrity and with exemplary loyalty to those at opposite ends of the spectrum, and everyone in-between. I think that captures it nicely, and defines the honoree, Michael Cooper.

It has been a lifetime of achievement, in keeping with the name of the award, but Michael has not lost his zeal. And so we might speak not of a life lived, but a living life, still marked by his benevolent impact on the legal community and beyond.

Albert M. Rosenblatt is a retired judge of the New York Court of Appeals.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Elizabeth Cooper of Simpson Thacher on Building Teams in a 'Relationship Business'

4 minute read

For Paul Weiss, Progress Means 'Embracing the Uncomfortable Reality'

5 minute read

Kenneth Feinberg Had Dreams of Being on the Big Screen. His 9/11 Victims Fund Gave Him an Unexpected Star Turn

City Bar Holds 32nd Annual Henry L. Stimson Medal Presentation

Trending Stories

- 1The New Rules of AI: Part 2—Designing and Implementing Governance Programs

- 2Plaintiffs Attorneys Awarded $113K on $1 Judgment in Noise Ordinance Dispute

- 3As Litigation Finance Industry Matures, Links With Insurance Tighten

- 4The Gold Standard: Remembering Judge Jeffrey Alker Meyer

- 5NJ Supreme Court Clarifies Affidavit of Merit Requirement for Doctor With Dual Specialties

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250