Federal Circuit Decision Raises Issues About Scope of Design Patents

The 'Curver Luxembourg' decision is a large step in resolving what had been open legal issues about the scope of design patents: Are design patents limited to specific "articles of manufacture" or do they also cover designs in the abstract? Does the title of the design patent (which must recite the article of the design) limit the scope of the patent grant (and hence the scope of potential infringement), the same way as claim terms do for a utility patent?

October 22, 2019 at 12:00 PM

11 minute read

Milton Springut

Milton Springut

A recent Federal Circuit decision, Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions (Fed. Cir. 2019), held, in what the court described as a matter of first impression, that a design patent for surface ornamentation entitled "Pattern for a Chair" was limited in scope to ornamental designs for chairs, and thus there was no infringement by the defendant who allegedly used the same pattern for a basket.

The Curver Luxembourg decision is a large step in resolving what had been open legal issues about the scope of design patents: Are design patents limited to specific "articles of manufacture" or do they also cover designs in the abstract? Does the title of the design patent (which must recite the article of the design) limit the scope of the patent grant (and hence the scope of potential infringement), the same way as claim terms do for a utility patent?

As do many landmark decisions, Curver Luxembourg resolves some old issues but then raises new ones, both for prosecution and litigation of design patents. In both prosecution of design patents and litigation over them, counsel must now be aware of how the title and word portion of the patent claims might limit the patent scope.

'Curver Luxembourg'

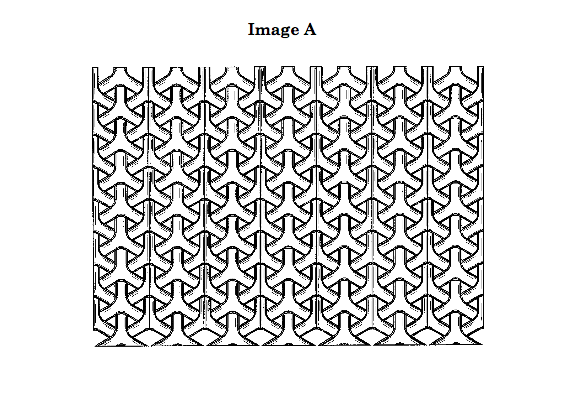

The decision involved U.S. Patent D677,946 (the '946 Patent), entitled "Pattern for a Chair." The '946 Patent covers a surface ornamentation, to be used to decorate part of the outside of a chair, that appears as indicated in Image A:

The Patent Act provides that "[w]hoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor." 35 U.S.C. §171(a). The emphasized language suggests that the design is not protectible in the abstract, rather it must be "for an article of manufacture."

The Patent Office takes that position. The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) requires that the title of the design patent must designate a "particular article" for the design. MPEP §1503.

The patent owner faced this very issue during prosecution of the '946 Patent. The application included as the title of the proposed design patent "Furniture (Part of –)" and the claim recited "a design for a furniture part." The Patent Office found these descriptions too vague to constitute an article of manufacture. At the Examiner's suggestion, the patent owner adopted "pattern for a chair" as the language in the claim and the title. The drawings, however, remained unchanged, without illustrating a chair specifically. The patent issued in that form.

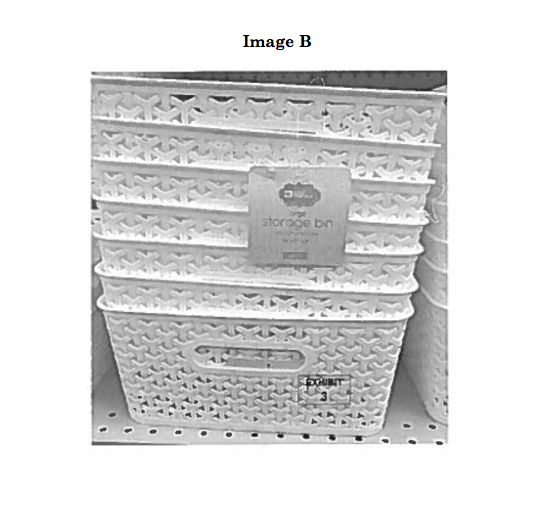

Sometime thereafter, Curver discovered that another company, Home Expressions, was selling baskets that incorporated a design very similar to that disclosed in the patent. See Image B.

Curver filed suit for design patent infringement in the District of New Jersey. The district court dismissed the complaint, as it construed the patent scope to be limited to patterns for a chair, and, under the accepted test for infringement, an ordinary observer would not confuse the defendant's basket with a chair incorporating Curver's patented design.

The Federal Circuit affirmed. It held that, while design patent drawings are the primary means by which design patents define the scope of their protection, the claim language ("pattern for a chair") also limits the scope.

After reviewing the statutory language, Supreme Court precedent, and long-standing Patent Office practice, the Federal Circuit concluded that design patents do not protect designs in the abstract.

Rather, "design patents are granted only for a design applied to an article of manufacture, and not a design per se," and thus the claim language, because it identified the article, would also limit the scope of the claim.

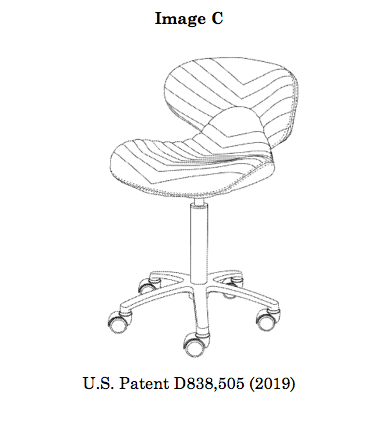

The Federal Circuit noted that the Curver Luxembourg case was atypical, because in most design patents, the drawings themselves depict a particular article of manufacture. A more typical design patent for a chair would have an illustration like the one in Image C:

Such a patent clearly is limited to a chair and would not cover a similar or analogous design for a basket.

The Curver Luxembourg decision now makes clear that design patents are limited in scope to the specific article of manufacture disclosed in the patent—and claim language, as well as drawings, may be used to limit the patent scope.

Issues Raised by the Decision

As often happens with important court decisions, they resolve one issue, however they raise new issues that counsel needs to be aware of and deal with.

Prosecution—Getting the Broadest Scope. So, what happens if an invention, like the surface ornamentation at issue in Curver Luxembourg, was created to be applied to multiple articles of manufacture? For example, the design in that case could have easily been applied to not only chairs, but to tables, footrests, and magazine racks, and one might imagine a manufacturer using the same design in a set of furniture items. (In fact, the same inventor has patented a number of baskets, and Curver itself sells baskets using the patented design. But, inexplicably, Curver did not attempt to patent its basket with the design.) As discussed, the file history of that patent indicates that the Patent Office would not allow claim language such as a "pattern for furniture."

One suggestion is to claim a pattern for multiple items—for a chair, table, footrest and magazine rack. But the applicable Patent Office regulations provide that "[t]he title of the design must designate the particular article," 37 CFR §1.153, and it is difficult to see how a list of articles qualifies.

Another suggestion would be to apply for multiple patents. But, it is conceivable that the Patent Office would reject this as double patenting. Double patenting is prohibited based on statutory grounds, since the Patent Act only permits "a patent" for each invention. 35 U.S.C. §171 According to the Patent Office, the test for double patenting is whether "the same design [is] being claimed twice." MPEP §1504.

One might argue that, under Curver Luxembourg, the "design" which is protected by a design patent is not the design in the abstract, but rather, a design as applied to a specific article, as the opinion expressly recites. The MPEP states that double patenting will only apply where the patents have "identical designs with identical scope." MPEP §1504. So, arguably, under Curver Luxembourg, a design for a chair is not the same as a design for a table, since they have different scope, and thus there would be no double patenting. But such arguments remain untested.

Prior Art. Curver Luxembourg also affects how prior art is assessed in relation to the validity of a design patent or patent application.

Prior art can invalidate a patent through anticipation—where the "the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention." 35 U.S.C. §102 (emphasis added). To anticipate, the prior art must disclose "the claimed invention"—meaning the same invention that is claimed in the patent.

The rule has long been that the same test for infringement applies to anticipation—that which infringes if it comes after, anticipates if it comes before. In fact, the Curver Luxembourg court noted this very rule, and thus rejected reliance on a case by its predecessor court, In re Glavas, 240 F.3d 447 (CCPA 1956), which had suggested in dictum that a prior art may anticipate, even if the prior art was for a different article. Apart from the fact that such was mere dictum, it was also inconsistent with later Federal Circuit decisions that set out how infringement is to be assessed.

The Federal Circuit's discussion of Glavas clearly indicates that, at least for anticipation, prior art will have to be for the same article, just as it would have to be for infringement, since the tests for the two are the same. Thus, if, hypothetically, someone had an earlier design patent for the same surface design, but for a table, for example, it would not anticipate the '946 Patent at issue in Curver Luxembourg.

Prior art can also invalidate a patent by rendering it obvious, specifically, "if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains." 35 U.S.C. §103. So, a design patent directed to a table could well render obvious a similar design patent directed to a chair.

This, however, can raise significant complications. For one thing, the test is whether "a person having ordinary skill in the art" would consider it obvious to apply the design in the prior art to the new article. In some cases, that can raise thorny factual issues, sometimes requiring expert testimony, to resolve.

Second, in determining obviousness, the analysis is generally limited to what is termed "analogous art," meaning an area of design that a designer would look to for guidance. Tables and chairs are likely analogous, but more disparate articles (handbags vs. computers, for example) might not be.

The MPEP cites the Glavas case for the rule that, when dealing with surface ornamentation, all prior art is considered "analogous" for the purpose of obviousness.

The question in design cases is not whether the references sought to be combined are in analogous arts in the mechanical sense, but whether they are so related that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.

Thus, if the problem is merely one of giving an attractive appearance to a surface, it is immaterial whether the surface in question is that of wallpaper, an oven door, or a piece of crockery …

Glavas, 230 F.2d at 450. The MPEP thus concludes: "where the differences between the claimed design and the prior art are limited to the application of ornamentation to the surface of an article, any prior art reference which discloses substantially the same surface ornamentation would be considered analogous art." MPEP §1504.03.

Whether this rule from Glavas survives the holding in Curver Luxembourg remains to be seen. In any event, Curver Luxembourg has now impacted assessment of prior art in design patent cases, both on the basis of anticipation and obviousness.

Copyright as an Alternative. Curver Luxembourg noted in a footnote that inventors of creative designs can also seek protection under Copyright law—and cited to Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands, 136 S.Ct. 1002 (2017). We previously wrote about the Star Athletica case, Decisions Highlight Need to Rethink IP Protection Strategies for Product Designs, 258 N.Y.L.J. 75 (Oct. 18, 2017), and its importance to product design protection. As we noted there, the case broadens copyright protection to two- and three-dimensional designs, so long as they can be conceived separately from the useful article to which they are applied.

It is very likely that the design which was the subject of the '946 Patent would have qualified for copyright protection. The design is similar to fabric designs which have long been held copyrightable. (It is not the same, since the design has three dimensions—the design patent discloses a slight elevation to the pattern.) The surface ornamentation clearly appears to be separable from the design of the chair—the design patent does not even show a chair at all, and one could easily imagine a chair remaining after the surface ornamentation was removed.

While the protections of design patents and copyrights are not the same, as a practical matter, both can provide significant protection. Under both regimes, the IP owner can obtain both injunctive relief, damages and/or disgorgement of the infringer's profits. And, copyrights are generally cheaper to obtain and quicker to register.

Not all designs are protectable by copyright; many are not "separable" from the useful article under Star Athletica. But serious consideration should be given to whether a design might also (or alternatively) be registrable under Copyright law.

Conclusion

The law of protecting product design continues to evolve—the Star Athletica case in 2017, and now the Curver Luxembourg decision this year, each impact on how intellectual property can be used to protect creative designs.

Both design patents and copyrights remain important tools to obtain such protection. Understanding the scope of these tools assists counsel to advise clients the most efficacious and cost-efficient way to protect their creations.

Milton Springut is a partner at Springut Law PC.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Judgment of Partition and Sale Vacated for Failure To Comply With Heirs Act: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Gunderson Dettmer Opens Atlanta Office With 3 Partners From Morris Manning

- 2Decision of the Day: Court Holds Accident with Post Driver Was 'Bizarre Occurrence,' Dismisses Action Brought Under Labor Law §240

- 3Judge Recommends Disbarment for Attorney Who Plotted to Hack Judge's Email, Phone

- 4Two Wilkinson Stekloff Associates Among Victims of DC Plane Crash

- 5Two More Victims Alleged in New Sean Combs Sex Trafficking Indictment

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250