Securities Act Claims in New York State Court: Trends and Observations a Year After 'Cyan'

In the wake of the 'Cyan' decision, the number of 1933 Act claims brought in state court has increased dramatically, with the most significant increase occurring in New York.

November 13, 2019 at 12:00 PM

10 minute read

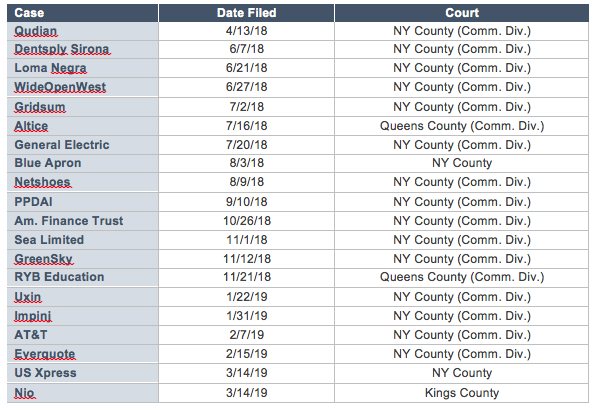

In March 2018, in Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, 138 S. Ct. 1061 (2018), the Supreme Court held that the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (SLUSA) did not strip state courts of concurrent jurisdiction over class actions alleging violations of the Securities Act of 1933 (1933 Act) where such lawsuits do not also assert claims under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (over which federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction). In the wake of the Cyan decision, the number of 1933 Act claims brought in state court has increased dramatically, with the most significant increase occurring in New York. In the first year after the Cyan decision, 20 cases pursuing 1933 Act claims were brought in New York state court.

In March 2018, in Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, 138 S. Ct. 1061 (2018), the Supreme Court held that the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (SLUSA) did not strip state courts of concurrent jurisdiction over class actions alleging violations of the Securities Act of 1933 (1933 Act) where such lawsuits do not also assert claims under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (over which federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction). In the wake of the Cyan decision, the number of 1933 Act claims brought in state court has increased dramatically, with the most significant increase occurring in New York. In the first year after the Cyan decision, 20 cases pursuing 1933 Act claims were brought in New York state court.

Cornerstone Research

Cornerstone ResearchNew York has quickly become one of the most active venues for actions of this type. As these cases proceed, New York courts have been faced, and will continue to be faced with, a number of important issues.

To date, New York courts have begun to address three issues in particular: (1) whether the automatic stay of discovery during the pendency of a motion to dismiss, as set forth in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA), applies to 1933 Act claims brought in state court; (2) whether a state court 1933 Act action should be stayed pending resolution of a parallel federal action arising from the same facts and circumstances; and (3) whether the circumstances underlying a 1933 Act claim must be pled with particularity pursuant to CPLR 3016(b).

Automatic Stay of Discovery

The issue of whether the PSLRA's automatic stay of discovery applies in New York state court has arisen repeatedly, with trial courts reaching different conclusions and appellate courts not having yet had occasion to weigh in. It was first addressed by Justice Saliann Scarpulla in In re PPDAI Group Securities Litigation and In re Dentsply Sirona Shareholders Litigation. Justice Scarpulla held in both cases that the PSLRA's automatic stay of discovery was not applicable in state court. Although the court's analysis of the issue in each case was very brief, Justice Scarpulla explained that, in her view, application of the stay "would undermine Cyan's holding that '33 Act cases may be heard in state courts." In re PPDAI Grp. Sec. Litig., 64 Misc.3d 1208(A), at *7 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. July 1, 2019); see also In re Dentsply Sirona Shareholders Litigation, 2019 WL 3526142, at *6 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. Aug. 2, 2019) (similar). She also noted that prior to the PPDAI decision there did not "appear to be any New York cases concerning th[e] issue" and that state courts in other states were divided. PPDAI, 64 Misc.3d 1208(A), at *7. The PPDAI and Dentsply decisions are both currently being appealed.

In contrast, in In re Everquote Securities Litigation, Justice Andrew Borrok reached the opposite conclusion. Justice Borrok explained that he "respectfully disagree[d] with the reasoning and conclusion" set forth in PPDAI and Dentsply and that "Cyan only addressed the jurisdictional issue as to whether [SLUSA] stripped state courts of jurisdiction to adjudicate claims brought under the 1933 Act and whether removal of such claims is permitted," not whether the PSLRA's automatic stay of discovery applies in state court. In re Everquote Sec. Litig., 65 Misc.3d 226, 228 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. 2019).

Turning to the statutory language, Justice Borrok explained that "[t]he simple, plain, and unambiguous language" of the PSLRA "expressly provides that discovery is stayed during a pending motion to dismiss '[i]n any private action arising under this subchapter'" and that nowhere "does the statute indicate that it applies only to actions brought in federal court." Id. at 236. Justice Borrok further explained that "[t]he 1933 Act is a federal statute," that "[i]t was Congress that created the specific rights covered by the 1933 Act including affording concurrent jurisdiction to state courts to adjudicate claims brought under the 1933 Act," that Congress "creat[ed] federal rules of decision that both state and federal courts are required to follow in deciding 1933 Act cases," and that among those rules of decision are the automatic stay of discovery. Id. at 239-40.

Finally, Judge Borrok noted that "a divergence in the application of the [PSLRA] discovery stay in state and federal court would create the undesirable (and unsupported by the text of the statute or its purpose) and absurd incentive for lawsuits brought under the 1933 Act to be brought in state court as opposed to federal court to avoid the very protection supporting the enactment of the [PSLRA] and necessarily confounding Congress' acknowledged intention that the lion's share of securities litigation would occur in the federal courts." Id. at 240.

A motion to stay discovery pursuant to the PSLRA's automatic stay is currently fully briefed and awaiting decision in In re GreenSky Securities Litigation, which is pending before Justice Jennifer Schecter. No. 655626/2018 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty.).

Stay Pending Resolution of Federal Action

In a number of recent cases, New York courts have stayed a state court 1933 Act case in favor of related, earlier-filed federal proceedings. For example, in In re Qudian Securities Litigation, Justice Peter Sherwood stayed further proceedings in that state court action, noting that the law firm that had sued in state court had done so only after it had "lost its bid to be named lead counsel in the consolidated [federal] actions" and that the state court action was its attempt at a "second bite at the apple." 2018 WL 6067209, at *1-2 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. Nov. 14, 2018). Justice Sherwood further noted that "[o]ther than some typos and other minor edits, the [state court complaint] is identical to the one filed by [the same law firm] in the [federal] action it started" and that "[n]o special circumstances exist to support departure from the usual first-filed rule." Id. at *1.

Similarly, in Gordon v. Gridsum Holdings, Justice Schecter granted the defendants' motion for a stay of the action pending resolution of the federal action. Order, No. 653342/2018, NYSCEF Doc. No. 46 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. April 10, 2019). Similar to Justice Sherwood's analysis in Qudian, Justice Schecter explained that "[t]he federal action was commenced first," "[p]laintiffs' counsel participated in those proceedings and moved to be appointed as lead counsel," and "[o]nly after withdrawing that motion in the federal case because its proposed plaintiff did 'not appear to have the largest financial interest' in the case" did the plaintiffs "subsequently commence[] this action." Id. at 1. Justice Schecter explained that allowing the state court case to proceed under those circumstances "would be an end-run around the federal court lead-counsel adjudication" and held that "[g]iven these facts and that the federal action may dispose of or limit the issues in this case, the duplication of effort, waste of judicial resources and possibility of inconsistent rulings outweigh any prejudice." Id. at 1-2.

Likewise, in Mahar v. General Electric Co., Justice Borrok stayed that state court action in favor of an earlier-filed federal action involving "the same subject matter or series of alleged wrongs" and "substantially the same parties" and seeking "substantially the same relief." 2019 WL 5382240, at *6 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. Oct. 15, 2019). Justice Borrok held that "the fact that this action involves claims under the 1933 Act and the Federal Action involves claims under the 1934 Act is not a reason to deny a stay motion [because] it is inconsequential that different legal theories or claims are set forth in the two actions" insofar as "the hallmark for a stay under First Department law is that both actions seek to recover for the same alleged harm based on the same underlying events." Id. In those circumstances, a stay "would avoid the risk of inconsistent rulings, ensure orderly proceedings (including coordinated discovery if the cases go forward) and preserve judicial resources." Id.

A motion to stay the state court action in light of a related federal action is currently fully briefed and awaiting decision by Justice Schecter in GreenSky.

Particularity in Pleading

New York courts have also begun to grapple with whether CPLR 3016(b), New York's heightened pleading standard for misrepresentation and fraud claims, should apply to 1933 Act claims. In In re Netshoes Securities Litigation, although Justice Borrok dismissed the complaint for failure to state a claim, he rejected the defendants' argument that CPLR 3016(b) should apply. 64 Misc.3d 926, 930-31, 941 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. 2019); see also Order at 7, 12, Dentsply, No. 155393/2018, NYSCEF Doc. No. 180 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. Sept. 26, 2019) (same).

CPLR 3016(b) is broader than its federal analogue (Rule 9(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure) and states that the "circumstances constituting the wrong shall be stated in detail" where "a cause of action or defense is based upon misrepresentation, fraud, mistake, willful default, breach of trust or undue influence." Insofar as one of the elements of a claim pursuant to §§11 and 12(a)(2) of the 1933 Act is a material misrepresentation (or, alternatively, in certain circumstances, a material omission), we expect defendants in actions brought in state court raising 1933 Act misrepresentation claims to argue that CPLR 3016(b) mandates that the underlying circumstances must be stated in detail and to cite case law standing for that proposition. See David v. Simware, 1997 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 201, at *9 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. March 7, 1997) (dismissing Securities Act claim for failure to comply with CPLR 3016(b)'s requirements); Regan v. Kidder Peabody & Co., 1991 WL 354937, at *6 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. July 3, 1991) (applying CPLR 3016(b)'s heightened pleading standard for misrepresentations to Securities Act claims even though "a pleading of misrepresentation under [15 U.S.C.] §77l of the [Securities] Act need not be particularized under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure").

This issue has been fully briefed and is awaiting decision in the WideOpenWest, Loma Negra, and Sea Limited cases referenced above.

Conclusion

It will be of particular interest to practitioners to see how New York trial and appellate courts resolve these issues. Moreover, if some of these cases proceed beyond the preliminary stages, they will likely raise additional issues about how New York courts should interpret provisions of the 1933 Act, the PSLRA, and SLUSA.

Samuel P. Groner is a litigation partner of Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson in New York. R. David Gallo is a litigation associate at the firm. The authors thank Cornerstone Research for providing the data cited in this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

9 minute read

Tortious Interference With a Contract; Retaliatory Eviction Defense; Illegal Lockout: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Pogo Stick Maker Wants Financing Company to Pay $20M After Bailing Out Client

- 2Goldman Sachs Secures Dismissal of Celebrity Manager's Lawsuit Over Failed Deal

- 3Trump Moves to Withdraw Applications to Halt Now-Completed Sentencing

- 4Trump's RTO Mandate May Have Some Gov't Lawyers Polishing Their Resumes

- 5A Judge Is Raising Questions About Docket Rotation

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250