Death of the DJ: The Decline of Declaratory Judgment Actions in Patent Disputes

Declaratory judgment actions, commonly referred to as "DJ actions," have historically provided a mechanism for companies threatened with a patent infringement claim to preemptively file a lawsuit seeking a court ruling declaring the patent invalid or not infringed. These DJ actions for years had been a popular tool for accused infringers, but as Rob Maier discusses in this edition of his Patent and Trademark Law column, recent changes in the patent litigation landscape have resulted in a shift away from these DJ actions, and a corresponding shift in the way patent holders approach infringers.

November 26, 2019 at 12:00 PM

8 minute read

Robert L. Maier

Robert L. Maier

Declaratory judgment actions, commonly referred to as "DJ actions," have historically provided a mechanism for companies threatened with a patent infringement claim, e.g., through a cease and desist letter sent by a patent holder, to preemptively file a lawsuit seeking a court ruling declaring the patent invalid or not infringed. These DJ actions for years had been a popular tool for accused infringers, but recent changes in the patent litigation landscape have resulted in a shift away from these DJ actions, and a corresponding shift in the way patent holders approach infringers.

Background

The Declaratory Judgment Act provides "in a case of actual controversy within its jurisdiction … any court of the United States, upon the filing of an appropriate pleading may declare the rights and other legal relations of any interested party seeking such declaration." 28 U.S.C. 2201(a). To bring a DJ action, a party must therefore demonstrate the existence of an actual case or controversy. In the patent context, that requirement is most often satisfied by an explicit or implicit threat of a patent lawsuit—for example, a letter from the patent holder putting the prospective defendant on notice of the its claim for infringement, and offering a license. Faced with the threat of a patent infringement suit, the accused party in these circumstances could then preemptively bring a DJ action to challenge the charge of infringement, or the validity of the subject patent.

These DJ actions were typically motivated, at least in part, by litigation strategy. Rather than being dragged into a court of the patent holder's choosing and on the patent owner's terms, the DJ action allowed the accused infringer to take charge of the dispute and bring the fight in a jurisdiction it chooses.

Previously, patent holders enjoyed nearly unlimited venue choices across district courts in the United States, and would often file in a district known to be friendly to patent holders, either procedurally or in terms of favorable jury pools and large damages awards. The DJ allowed an alleged infringer to seize the patent holder's ability to forum shop, and instead file in a hometown court or other court it deemed advantageous. So significant was this strategy point that patent holders historically considered with great care what they said in communications with alleged infringers—and how they said it—stopping short of threats that would trigger an "actual case or controversy" that would otherwise allow an accused infringer to bring a DJ action.

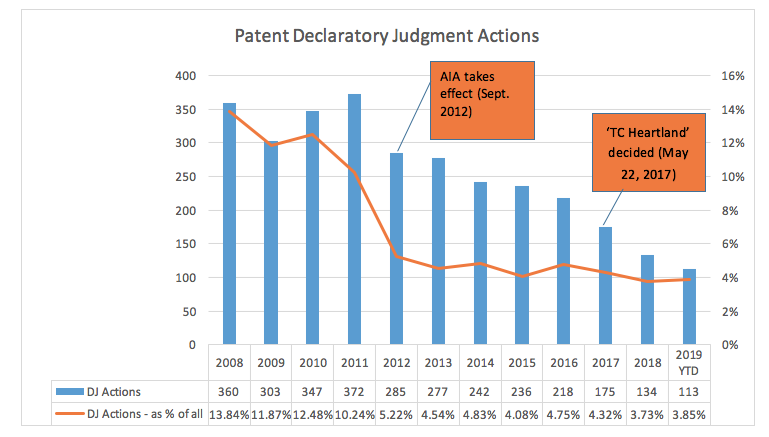

Decline in Patent DJ Action Filings

Two factors in recent years have taken the teeth out of DJ actions and triggered a steep decline in DJ action filings. These filings first declined in 2012, immediately following passage of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, which established a Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office that hears expedited patent validity challenges. These proceedings, such as Inter Partes Review (IPR), make it easier, faster, and less expensive to invalidate patents than in a district court, and have therefore become a tool of choice in patent defense strategy.

How do these PTAB proceedings impact DJ action filings? By statute, these proceedings may not be instituted if "before the date on which the petition for such a review is filed, the petitioner or real party in interest filed a civil action challenging the validity of a claim of the patent." 35 U.S.C. §315(a). In other words, if an accused infringer were to file a DJ action in a district court seeking a declaration of invalidity, it could not thereafter invalidate the patent at the PTAB. The steep decline in DJ actions filed in 2012 and continuing thereafter is a direct result of the rise of PTAB proceedings as the preferred mechanism for challenging the validity of a patent.

The second contributing factor came some years later. In May 2017, the Supreme Court decided TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods Grp. Brands, 137 S. Ct. 1514 (2017). In TC Heartland, the Supreme Court interpreted the patent venue statute, 28 U.S.C. §1400(b), and held that patent holders would no longer enjoy virtually unlimited venue choices nationwide, but rather could only sue in the state in which the defendant is incorporated, or "where the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business." TC Heartland, 137 S. Ct. at 1516-17. The Supreme Court thus stripped patent holders of their ability to forum shop. And, accordingly, parties threatened with a patent suit no longer have to be as concerned about being dragged into a faraway district that is highly plaintiff-friendly—instead, parties know they can only be sued in a limited number of places, one often being the District of Delaware, a sophisticated patent court where most companies are incorporated, and others being a party's home court jurisdictions where they conduct meaningful business operations. As a result, the strategic advantage in affirmatively filing a DJ action to avoid an unfavorable jurisdiction no longer applies.

The filing data supports these points. In 2017 the number of patent DJ actions dropped below 200 for the first time since 2008. In fact, the number of DJ action filings have not been this low since 2002—133 DJ actions were filed in 2002, nearly matching the 134 filed in 2018.

Source: DocketNavigator

Source: DocketNavigatorGiven this shift in the landscape, patent holders now can be more direct in their communications to would-be licensees. In the past, parties and their attorneys would take great care in drafting letters to potential licensees, doing so softly and in a way that would, they hoped, fall short of creating a case or controversy for DJ purposes, but which, at the same time, still conveyed sufficient gravity that the alleged infringer would be prompted to consider paying for a license. Sometimes this dance resulted in a slow and protracted escalation before any serious licensing discussions proceeded. Now, given the diminishing of this strategy concern, a patent holder is free to be more forceful at the outset, and can thereby accelerate the discussions.

Are Rumors of DJ's Death Greatly Exaggerated?

While DJ action filings are down, they are not necessarily out. In some unique circumstances, the DJ action may still have strategic value. For example, accused infringers with regular and established places of business in multiple districts may still seek to file a DJ action to control selection of venue from among the multiple districts in which they could be sued.

There may even be room for an alleged infringer to have its cake and eat it too. While the filing of a DJ action asserting invalidity of a patent will preclude a subsequent PTAB proceeding, a DJ action asserting only non-infringement will not, because it does not constitute "a civil action challenging the validity of a claim of the patent" for purposes of the statute. 35 U.S.C. §315(a)(1)). And further still, at least one PTAB panel has acknowledged in a non-precedential decision that a party that files a DJ action seeking only a declaration of non-infringement, which is met with an infringement counterclaim by the patent holder, can then in response bring a counterclaim for invalidity and still maintain the ability to subsequently invalidate the patent at the PTAB. Canfield Sci. v. Melanoscan, IPR2017-02125, 2018 WL 1628565, Paper No. 15 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 30, 2018). In Canfield, the PTAB found that an IPR petition was not barred because, as specified in 35 U.S.C. §315(a)(3)), "[a] counterclaim challenging the validity of a claim of a patent does not constitute a civil action challenging the validity of a claim of a patent [for purposes of subsection (a)(1)]." Id. at *2; see also Diagnostics v. Ltd., IPR2012-00022, 2013 WL 2181162, at *6 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 12, 2013).

The bottom line: Use of the DJ has rapidly declined in recent years, as a direct result of meaningful changes brought by both Congress and the Supreme Court. In the vast majority of cases, a DJ action will no longer bring the strategic advantages it once did. That said, practitioners and patent litigants should not discount the value of DJ actions entirely—instead, they should be considered in every case, based on the specific facts and circumstances and party objectives. In some cases, the DJ action may still be a useful tool for responding to a charge of patent infringement.

Rob Maier is an intellectual property partner in the New York office of Baker Botts, and the head of its intellectual property group in New York. Joe Akalski, a Baker Botts senior associate, assisted in the preparation of this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Big Law Sidelined as Asian IPOs in New York Are Dominated by Small Cap Listings

The Benefits of E-Filing for Affordable, Effortless and Equal Access to Justice

7 minute read

A Primer on Using Third-Party Depositions To Prove Your Case at Trial

13 minute read

Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

9 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1OCR Issues 'Dear Colleagues' Letter Regarding AI in Medicine

- 2Corporate Litigator Joins BakerHostetler From Fish & Richardson

- 3E-Discovery Provider Casepoint Merges With Government Software Company OPEXUS

- 4How I Made Partner: 'Focus on Being the Best Advocate for Clients,' Says Lauren Reichardt of Cooley

- 5People in the News—Jan. 27, 2025—Barley Snyder

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250