Design Patents: 'Campbell Soup' Stirs the Pot

If and only if a primary reference is found having design characteristics basically the same as the claimed design, secondary references may be considered to suggest modifications of that design to test the obviousness of the claimed invention. In its recent decision in 'Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus', however, the Federal Circuit appeared to soften this requirement.

December 09, 2019 at 11:00 AM

13 minute read

It has been hornbook law for decades that obviousness in the design patent context requires the threshold existence of a primary reference—"a something in existence"—against which to compare the claimed design. If and only if a primary reference is found having design characteristics basically the same as the claimed design, secondary references may be considered to suggest modifications of that design to test the obviousness of the claimed invention. In its recent decision in Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus (Fed. Cir. Sept. 26, 2019), however, the Federal Circuit appeared to soften this requirement. Vacating and remanding a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) upholding the validity of two design patents claiming ornamental designs of a soup can dispenser display, the Federal Circuit concluded substantial evidence did not support the PTAB's finding that a reference was insufficiently similar to the claimed designs to be a primary reference. The Federal Circuit reached this conclusion though the design disclosed in the reference was missing, according to the PTAB, half the scope of the claimed design—specifically, a display can—because the prior art design was "made to hold" a cylindrical object in the display area. In reaching this conclusion over Judge Pauline Newman's dissent, Judge Kimberly Moore, writing for herself and Chief Judge Sharon Prost, implicitly permitted modification of the design disclosed by the prior art reference before determining the reference to be a primary reference, opening the door, perhaps, to similar utilitarian considerations in future design patent cases.

It has been hornbook law for decades that obviousness in the design patent context requires the threshold existence of a primary reference—"a something in existence"—against which to compare the claimed design. If and only if a primary reference is found having design characteristics basically the same as the claimed design, secondary references may be considered to suggest modifications of that design to test the obviousness of the claimed invention. In its recent decision in Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus (Fed. Cir. Sept. 26, 2019), however, the Federal Circuit appeared to soften this requirement. Vacating and remanding a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) upholding the validity of two design patents claiming ornamental designs of a soup can dispenser display, the Federal Circuit concluded substantial evidence did not support the PTAB's finding that a reference was insufficiently similar to the claimed designs to be a primary reference. The Federal Circuit reached this conclusion though the design disclosed in the reference was missing, according to the PTAB, half the scope of the claimed design—specifically, a display can—because the prior art design was "made to hold" a cylindrical object in the display area. In reaching this conclusion over Judge Pauline Newman's dissent, Judge Kimberly Moore, writing for herself and Chief Judge Sharon Prost, implicitly permitted modification of the design disclosed by the prior art reference before determining the reference to be a primary reference, opening the door, perhaps, to similar utilitarian considerations in future design patent cases.

Factual Background

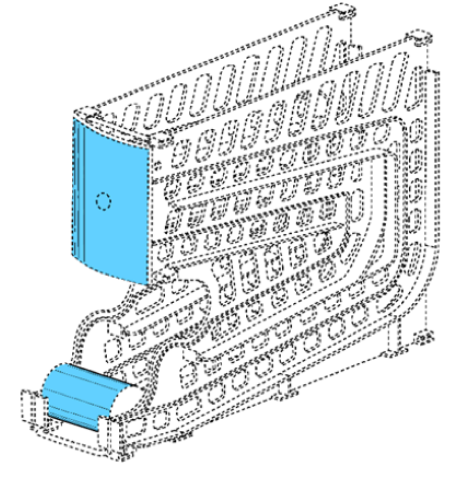

Campbell Soup concerns two U.S. design patents, D621,645 and D621,646, owned by Gamon Plus. The '645 patent claims the "ornamental design for a gravity feed dispenser display" shown in Image A:

Image A

Image ABecause dotted lines reflect disclaimed design elements, the only portions of the design claimed are those shaded in blue. (The figure with shading is taken from a court document, not the patent.) Note that the lower element of the claimed design is a soup can, which would not, of course, be part of a commercial article of manufacture. The '646 patent is similar, the main difference being inclusion as part of the claimed design of the two stop tabs holding the can in place. For simplicity, the discussion that follows addresses only the '645 patent.

According to the PTAB decision, the patentee came up with his design after having difficulty finding a can of home-style chicken noodle soup in the grocery store. He purchased instead a can of plain chicken noodle soup "that did not go over well at home." His solution to this problem was a display combining a dispensing element for sideways cans with a convex sign conveying the visual impression of an enlarged upright can, as illustrated by the commercial embodiments show in Image B:

Image B

Image BThough the dispenser was designed specifically for cans of Campbell Soup, Campbell was initially reluctant to adopt the patented design. After a market study showed material increases in soup sales, however, Campbell purchased tens of millions of dollars of dispensers from Gamon, placing display racks in about 30,000 stores.

Several years later, Campbell began purchasing similar dispensers from another company. Gamon accused that manufacturer of copying the claimed design and sued the manufacturer, Campbell, and others (collectively "Campbell") for patent infringement. Campbell commenced inter partes review (IPR) proceedings. Among other contentions raised in the IPR petitions, Campbell argued the claimed invention was obvious over U.S. design patent D405,622 to Linz in combination with other art. Linz disclosed and claimed a display rack as depicted in Image C:

Image C

Image CThough certain similarities between Linz and the claimed invention are evident, one feature of the claimed design notably absent from Linz is a can or like cylindrical object. Initially viewing Linz as basically the same as the patented design "when a can is added to the Linz design" and therefore suitable as a primary reference, the PTAB instituted IPR proceedings.

During the IPR, the PTAB concluded the patented invention claims "certain front portions of a gravity feed dispenser display," described as follows:

From top to bottom, a generally rectangular surface area, identified by the parties as an access door or label area, is curved convexly forward. … The label area is taller vertically than it is wide horizontally, however, the boundary edges of the label area are not claimed. Below the label area there is a gap between the label area and the top of a cylindrical object lying on its side – the gap being approximately the same height as the label area. The width of the label area is generally about the same as the height of the cylindrical object lying on its side. The height of the cylindrical object (lying on its side) is longer than its diameter. The cylindrical article is positioned partially forward of the label area.

Given that claim construction and on a fuller record, the PTAB changed its position on Linz. Quoting In re Rosen, 673 F.2d 388, 391 (CCPA 1982), the PTAB stated the patented design must be "compared with something in existence—not with something that might be brought into existence by selecting individual features from the prior art and combining them." The PTAB rejected Campbell's obviousness analysis, which began by modifying Linz to include a cylindrical can lying on its side, which the PTAB found Linz did not disclose. The PTAB further found that various secondary indicia of non-obviousness (including Gamon's sales to Campbell of gravity dispensers and Campbell's copying and praise of Gamon's design) warranted a finding of non-obviousness.

The Appeal

On appeal, one of Campbell's primary arguments was that the PTAB had misconstrued the patent claim. (Not incidentally, because claim construction presents a question of law, this issue was subject to de novo review, whereas the PTAB's findings with respect to Linz were subject to more deferential review for substantial evidence.) Dotted lines show disclaimed subject matter. It was therefore error, Campbell argued, for the PTAB to construe the claim to include relative dimensions of the label area and cylindrical object and a spatial relationship between the two. Because the boundaries of both the label area and the cylindrical object are undefined, these relationships are likewise undefined, according to Campbell. The claim construction was important to Campbell's argument because Linz does not actually disclose any particular cylindrical object. Thus, even if one assumed such an object, as Campbell urged the court to do, it would be hard to say the height of the hypothetical object is longer than its diameter or the gap between the label area and the top of a cylindrical object is approximately the same height as the label area, as the PTAB's construction requires. Gamon persuasively argued, however, that an unclaimed boundary line disclaims the portion of the design beyond the boundary while claiming the area within it. The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB's claim construction in a footnote.

Campbell was thus required to show the PTAB lacked substantial evidence for its finding that Linz was not "basically the same" as the claimed design even after the spatial relationships required by the PTAB's claim construction were deemed appropriate. In view of Linz' failure—at least expressly—to disclose a cylindrical object at all, this was, or at least appeared to be, a heavy lift. Campbell argued unrebutted testimony showed a designer of ordinary skill would have understood the Linz dispenser was designed to hold a cylindrical object and six of the seven references cited on the first page of Linz were directed to dispensers for cylindrical objects. Campbell thus argued the PTAB was wrong to reject Linz as a primary reference where it "otherwise conveys basically the same visual impression as the claimed designs." Gamon, in turn, argued Campbell was attempting to modify Linz in hindsight and with resort to utilitarian rather than design principles. Because Campbell's evidence and arguments provided no answer for Gamon's contention that Linz failed to disclose a design having the spatial relationships defined by the claim, the Federal Circuit's affirmance of the PTAB's claim construction appeared to give Gamon the better of the argument.

Nonetheless, remarking that the case presented "the unusual situation where we reverse the Board's factual finding that Linz is not a proper primary reference for lack of substantial evidence support," the court observed the parties agreed the Linz design was for dispensing cans and reduced Gamon's arguments about the spatial relationships among the elements of the design to what it deemed a trivial dispute about the dimensions of the can that would be used in Linz. Having done so, the court found "the ever-so-slight differences in design, in light of the overall similarities, do not properly lead to the result that Linz is not a 'single reference that creates "basically the same" visual impression' as the claimed designs." Because Gamon did not dispute "that Linz's design is made to hold a cylindrical object in its display area," the court concluded the PTAB's "finding that Linz is not a proper primary reference is not supported by substantial evidence."

Judge Newman dissented: "My colleagues propose that since 'Linz is made to hold a cylindrical object in its display area, … the Linz design must be viewed with judicial insertion of the missing cylindrical object. This analysis is not in accord with design patent law. Only after a primary reference is found for the design as a whole, is it appropriate to consider whether the reference design may be modified with other features." She explained: Even if the "only claimed design elements are the label area and the cylindrical object, the cylindrical object is a major component of the design. The absence from a primary reference of a major design component cannot be deemed insubstantial." Judge Newman objected to what she regarded as the improper molding of concepts of utility obviousness into the design patent obviousness analysis. Quoting the PTAB, she concluded Campbell's analysis did not consider, as required, "a design currently in existence, but a potential design based on [the witness'] assumption of how utilitarian features like curved rails indicates that a can could be displayed."

The Future

Though the decision is obviously a setback for Gamon and new life for Campbell, there is good reason to doubt the Federal Circuit decision will have a material impact on the ultimate outcome of that particular litigation. As noted above, the PTAB concluded there was strong evidence of multiple secondary considerations of non-obviousness supporting an ultimate finding of non-obviousness. Because the PTAB had rejected Linz (and certain other invalidity contentions) at the threshold for lack of a primary reference, the Federal Circuit vacated the finding of non-obviousness, but it did not reach Campbell's arguments with respect to the secondary indicia. Upon remand, the PTAB must consider the differences between the prior art, bearing in mind its own claim construction (now law of the case) and Linz's failure to disclose the relative dimensions and spatial relations of the disclosed design, in light of the secondary indicia of non-obviousness, which it has already suggested support an ultimate determination of non-obviousness. Thus, there is reason to expect the validity of the '645 and '646 patents may again be upheld, at least in the IPR proceeding, in relatively short order. (The district court infringement action is stayed. If Campbell can locate evidence of the use in the United States of the Linz design with cans, it might hope to succeed in proving invalidity in the district court where proof will not be limited to patents and other printed publications, notwithstanding the heightened burden of proof. Such arguments, moreover, based on evidence the PTAB cannot consider, should not be estopped.)

More interesting, however, is the question whether the Campbell Soup decision will have long-term impact on validity arguments in design patent cases. There appears now at the least to be a chink in the armor of the patentee under what had been well-settled law that a primary reference must be found at the threshold on the basis of "a something in existence" without modification. While there is substantial force in the majority's conclusion that Linz was "made" to dispense cans, evaluating Linz as a primary reference inclusive of a can is nonetheless a modification of its actual disclosure, particularly in the design patent space where, notwithstanding the majority's dismissal of Gamon's dispute about "dimensions," dimensions matter.

Campbell Soup certainly does not explicitly suggest a revision of the requirement of "a something in existence." Moreover, despite Judge Newman's dissent asserting a departure from settled law, perhaps the decision may not even fairly be read to imply a revision either. Indeed, Campbell Soup also urged first the PTAB and then the Federal Circuit to treat an alternate reference, a UK patent application by Samways, as a primary reference, and the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB's rejection of Samways as a primary reference. Unlike Linz, the Samways application was for a utility patent. It disclosed and illustrated a gravity feed dispenser for cylindrical objects (such as coffee jars) having two dispensing outlets. The convex label area extended over both outlets and had substantially different dimensions than those described by the PTAB with respect to the patented design of the '645 patent. In view of these differences, the Federal Circuit found substantial evidence supported the PTAB's finding that Samways was not a proper primary reference. The court reached this conclusion even though Samways expressly discloses a single-path dispenser. According to Samways: "Whilst in the embodiments above the dispensers have two delivery paths for delivering coffee, it should be appreciated that a dispenser according to the invention could have any number of delivery paths, from one upwards." None of its figures, however, illustrated a one-path embodiment, and both the PTAB and the Federal Circuit regarded the one-path embodiment as an embodiment separate from the illustrated embodiment and not in existence.

In view of the court's different regard for Linz and Samways, the limiting principle of Campbell Soup is not entirely clear. Why should the fact that Linz was "made" to dispense cans make it a viable primary reference when cans—though implicit or inherent—were not shown, when Samways is not a viable primary reference—though expressly describing a single-path embodiment—merely because no single-path embodiment was pictured? Do utilitarian principles apply to design patent references, but, paradoxically, not to utility patents? However the answers to these questions play out in future cases, Campbell Soup has at the least fairly raised them, creating some uncertainty concerning the identification of primary references that did not previously exist.

Jonathan Tropp is a partner at Day Pitney.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'Serious Legal Errors'?: Rival League May Appeal Following Dismissal of Soccer Antitrust Case

6 minute read

How Some Elite Law Firms Are Growing Equity Partner Ranks Faster Than Others

4 minute read

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Mastering Litigation in New York’s Commercial Division Part V, Leave It to the Experts: Expert Discovery in the New York Commercial Division

- 2GOP-Led SEC Tightens Control Over Enforcement Investigations, Lawyers Say

- 3Transgender Care Fight Targets More Adults as Georgia, Other States Weigh Laws

- 4Roundup Special Master's Report Recommends Lead Counsel Get $0 in Common Benefit Fees

- 5Georgia Justices Urged to Revive Malpractice Suit Against Retired Barnes & Thornburg Atty

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250