'The Guarded Gate': Remember the Mistakes of the Past

In his latest book, Daniel Okrent examines the 1924 statute and "eugenics," the pseudoscience employed to justify the act's restrictions and prevent so-called ruinous "genetic traits" from poisoning America.

December 24, 2019 at 10:00 AM

9 minute read

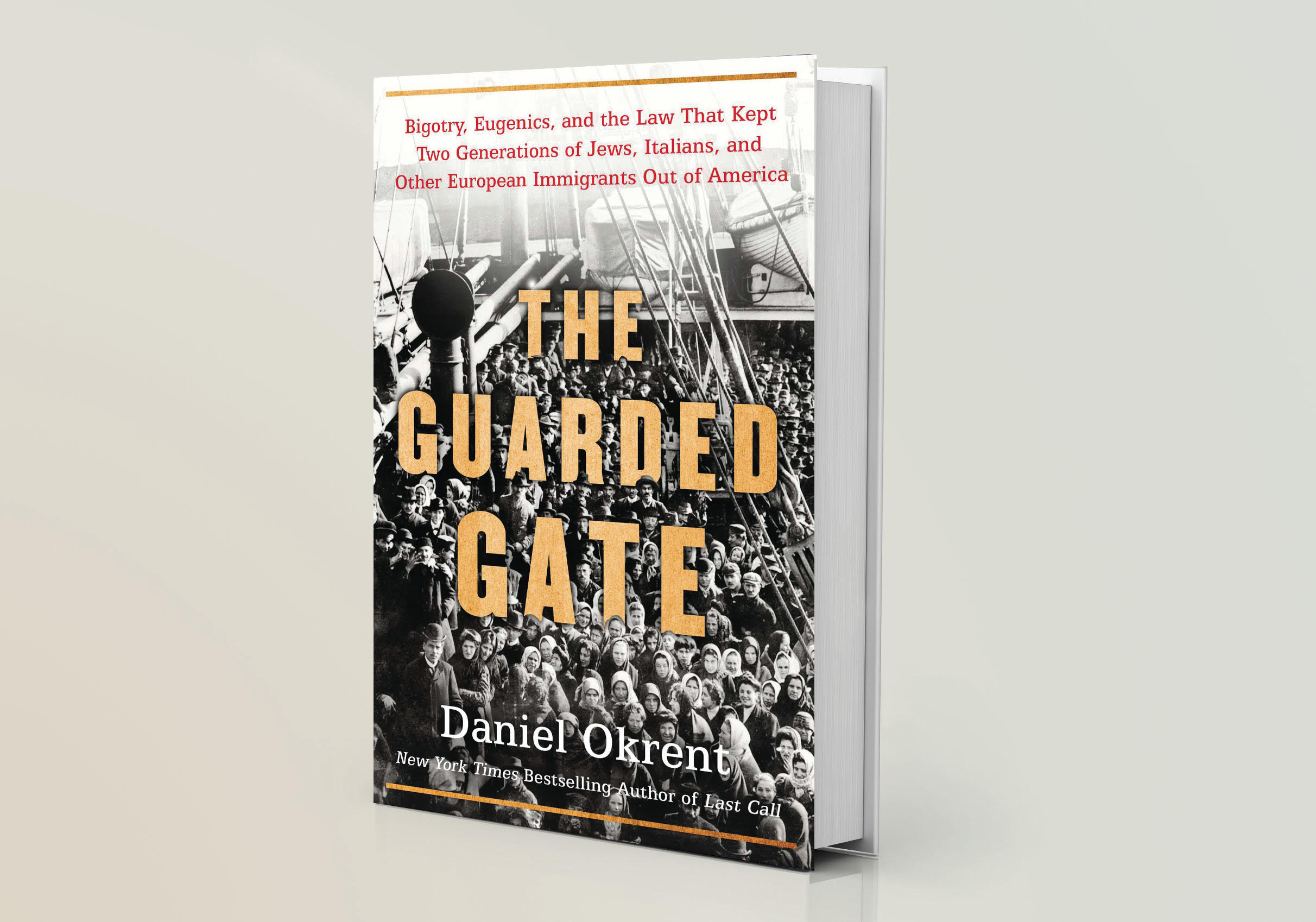

'The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America'

By Daniel Okrent

Scribner, New York, 496 pages, $32

With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, the United States restricted immigration through "national origin quotas," which discriminatorily limited immigration levels of southern and eastern Europeans, whom critics deemed as nonwhite and undesirable. In enacting the most restrictive barrier in U.S. history, proponents openly sought to create a specific American identity and restore a Nordic ethnic homogeneity. One person who admired the 1924 statute was Adolf Hitler, who in that same year from Landsberg Prison laid out his plans in Mein Kampf for transforming German society into one based on race.

In his latest book, Daniel Okrent examines the 1924 statute and "eugenics," the pseudoscience employed to justify the act's restrictions and prevent so-called ruinous "genetic traits" from poisoning America. The book's title is inspired by the famous 1895 poem entitled "Unguarded Gates," in which the author, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, a leading immigration critic, complained of "the wild motley throng." As Okrent observes, eugenics became discredited as racist and classist in the United States by the 1930s. However, the discriminatory national origin quotas remained largely intact until repealed in 1965. In its wake, the 1924 statue left behind a 40-year legacy of bias, disaster, and regret.

Okrent is a first-rate man of letters who formerly served as the initial public editor of the New York Times, editor at large of Time, Inc., and managing editor of Life magazine. He is also the author of several books, including Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, arguably one of the best books ever written on that subject.

Since the nation's founding, race has played a central role in immigration and naturalization. The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited naturalization to those of white descent. The Naturalization Act of 1870 extended naturalization rights to those of African descent, but revoked the naturalized citizenship of Chinese Americans. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese people from immigrating to the United States, while the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 barred the immigration of members of the Japanese working class.

Between 1870 and 1920, the U.S. population grew from 38 million to 106 million. During that time, the U.S. admitted an estimated 11 million immigrants. Until the 1880s, most U.S. immigrants came from Germany, western Europe, the U.K., and Scandinavia. Beginning in the 1880s, however, U.S. immigrants increasingly consisted of Italians, Jews, Greeks, Poles, and Slavs from southern and eastern Europe.

Also in the 1880s, eugenics emerged as an academic and political force in the United States and England. Although the eugenics movement emerged independently from U.S. political doctrine that advocated for restricted immigration, politicians soon used eugenics to dress up their nativist policies in supposed respectable garb.

As described in the book, the man who coined the term "eugenics" was Sir Francis Galton, an English Victorian era academic. Galton aimed to improve the genetic quality of human population through a statistical understanding of heredity and "good breeding habits." Galton was the cousin of Charles Darwin, whose book, The Origins of the Species (1859), heavily influenced his work, even though Darwin did not focus on variations in human populations.

Eugenics became associated with genetic determinism, which posits that human character is largely caused by genes, not education or living conditions. To improve the human populations, eugenic "scientists" urged the exclusion of inferior groups. People deemed unfit to reproduce included those who scored low on intelligence tests, the mentally and physically challenged, alcoholics, criminals, deviants, and members of minority groups.

In addition to Galton, Okrent focuses on the many Americans who figured prominently in the eugenics movement. Three of these stand out. All happened to be New Yorkers.

Charles Davenport was a zoology professor who became the director of the most prominent eugenics think tank, the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, located on Long Island. Davenport investigated the inheritance of personality traits, generating dubious literature about the genetics of alcoholism, pellagra (vitamin deficiency), lawlessness, feeblemindedness, ill temper, intelligence, manic depression, and the purported biological and cultural degradation of miscegenation. During the 1930s, Davenport maintained connections with various Nazi publications and institutions in Germany.

The book also recounts Harry Laughlin, who served as the Superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office, which was generously funded by Mary Harriman, the wealthy widow of the founder of the Union Pacific Railroad. In support of the 1924 statute, Laughlin provided statistical testimony to Congress, a portion of which dealt with the purported excessive insanity which afflicted immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

Laughlin was also a leading proponent of sterilization laws, which were adopted in 30 U.S. states. Laughlin drafted the Model Eugenical Sterilization Law, which targeted the feeble-minded, the insane, criminals, epileptics, alcoholics, blind persons, deaf persons, deformed persons, and indigents. In Buck v. Bell (1927), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Virginia sterilization law. Luminaries such as Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and Louis Brandeis voted with the majority. Enforced by some states into the 1970s, these eugenics-inspired laws were used to sterilize over 60,000 Americans. The Nazis passed a similar law in Germany in 1933, which was based on Laughlin's work.

Okrent also examines the work of Madison Grant, a New York lawyer and conservationist. In 1916, Grant published an influential eugenics book, entitled The Passing of the Great Race, which lamented the recent change of U.S. immigration "stock," in which Nordics were replaced with immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Grant pontificated that Nordics were committing "race suicide," because they had been engaging in miscegenation and being "outbred by inferior stock." Grant advocated for the separation and collapse of "worthless race types" from the human gene pool to promote a Nordic society.

The Passing of the Great Race sold so well that it was translated into German. Hitler was a fan, writing to Grant: "The book is my Bible." Posing as an "expert" on "world racial data," Grant provided statistics in support of passage of the 1924 statute.

Another prominent figure highlighted by Okrent is Franz Boas, the legendary Columbia professor who is considered the father of modern anthropology. Boas was a fierce critic of eugenics in general, and of The Passing of the Great Race in particular. Boas' work demonstrated that human behavioral differences were largely the result of cultural differences obtained through social learning, not biology. For this, Grant tried unsuccessfully to get Boas fired from Columbia. Avowedly anti-Hitler, Boas became known as one of the greatest scientists of his day.

In summing up eugenics, Okrent observes that it "was all a hyper-inflated display of presumed expertise by men who were not experts preaching the lessons of a science that was not science, thus justifying prejudices too ugly to be acknowledged."

Okrent also recounts well anti-immigration politicians such as Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA), whose views not only found support in eugenics, but also culminated in the passage of the 1924 statute, which enjoyed broad bi-partisan support at the time of its passage. As noted by Okrent, one of the few House members to vote against passage was a freshman Democrat from Brooklyn, Rep. Emmanuel Celler.

The 1924 statute established a total annual immigration quota of 165,000 outside the western hemisphere, which was an 80% reduction from pre-World War I levels. Between 1901 and 1914, approximately 210,000 Italians on average immigrated to the United States each year. After the passage of the 1924 statute, Italian immigration was restricted to a mere 4,000 per year. The new restrictions were so onerous that, after 1924, more people from southern and eastern Europe left the United States than arrived as immigrants.

As adroitly observed by Okrent, the 1924 statute not only inspired Nazi leaders to target "non-Aryans" throughout its genocidal regime, but it also erected a U.S. legal barrier which precluded most Third Reich refugees from seeking refuge in America before and during World War II. Okrent further observes that, without the 1924 law, the United States could have possibly and legally admitted hundreds of thousands of Hitler's victims before the Holocaust enveloped them.

The 1924 statute was finally repealed by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the national origin quotas and removed discrimination against immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe. As noted by Okrent, the chief House sponsor was Rep. Emmanuel Celler, now a 40-year congressional veteran.

Since the passage of the 1965 statute, U.S. immigration has increased, particularly from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and southern and eastern Europe. This has markedly changed the demographic mix of the United States, which for the first time will become more than 50% nonwhite by 2045.

Okrent's book is timely, given the recent resurgence of political discourse in America that recycles rationales that were popular with the eugenics movement and sympathetic to the results achieved by the 1924 national origin quotas. Such discourse fails to respect the increasingly diverse nature of the United States, which in the years to come will require new methods to share space and power. Such discourse also rekindles old biases, risking the repetition of past mistakes that unfairly marginalized many communities, including those who were targeted by the 1924 statute. Like the philosopher George Santayana, Okrent's book reminds us that those who do not remember the mistakes of the past are condemned to repeat them.

Jeffrey M. Winn is an attorney with the Chubb Group, a global insurer, and a member of the executive committee of the New York City Bar Association.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'We Learn Much From the Court's Mistakes': Law Journal Review of 'The Worst Supreme Court Decisions, Ever!'

6 minute read

'Midnight in Moscow': A Memoir From the Front Lines of Russia's War Against the West

9 minute read

'There Are Heroes in Every Story': Review of 'The Eight: The Lemmon Slave Case and the Fight for Freedom'

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Uber Files RICO Suit Against Plaintiff-Side Firms Alleging Fraudulent Injury Claims

- 2The Law Firm Disrupted: Scrutinizing the Elephant More Than the Mouse

- 3Inherent Diminished Value Damages Unavailable to 3rd-Party Claimants, Court Says

- 4Pa. Defense Firm Sued by Client Over Ex-Eagles Player's $43.5M Med Mal Win

- 5Losses Mount at Morris Manning, but Departing Ex-Chair Stays Bullish About His Old Firm's Future

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250