The Spaniards Address International Commercial Arbitration in the 21st Century

In their International Litigation column, Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky examine some of the more innovative ways that the recently-promulgated CEA Code of Best Practices in Arbitration (together with the Model Arbitration Rules annexed to the Code) deal with the various participants to arbitration, including arbitral institutions, arbitrators, lawyers, expert witnesses, tribunal secretaries and third-party funders.

January 22, 2020 at 12:00 PM

11 minute read

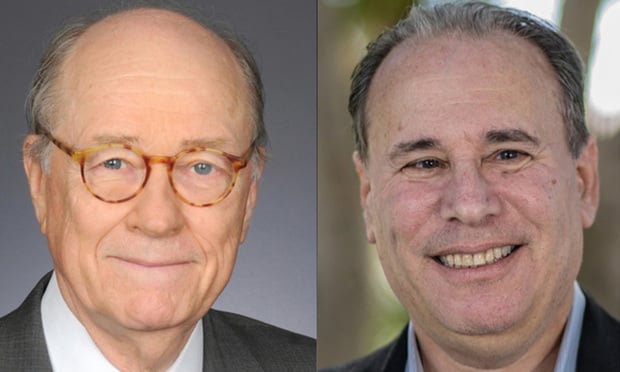

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Lawrence W. Newman and David Zaslowsky

Our recent passing into the third decade of the 21st century might be considered an appropriate time to assess what the near future may have in store for the conduct of international commercial arbitration. The past several years have seen increasing activity in international arbitration, marked by a proliferation of books, articles, conferences and organizations dealing with international arbitration. Some activity has been negative: growing criticism of mandatory domestic arbitration for consumer and employment disputes and of the ways in which international arbitration has been used for disputes between investors and foreign states. Accusations of unconscionability in the former and lack of transparency and perceived unfair outcomes in the latter have frequently been accompanied by assertions that commercial arbitration has become too complex and expensive in comparison with litigation. Arbitral institutions have begun to respond to some of these criticisms by adjusting their rules and recommended practices.

Some indication as to how these and other concerns may be dealt with going forward may be discerned through a review of proposed guidelines recently promulgated by the Spanish Arbitration Club (Club Español del Arbitraje), the "CEA Code of Best Practices in Arbitration."

The promulgation of the CEA Code has coincided in timing with the merger of the three largest Spanish arbitral institutions (a private association and two chambers of commerce) to form, together with the Madrid Bar Association, the new Madrid International Arbitration Center (MIAC), to administer, starting on Jan. 1, 2020, newly filed international arbitrations of those bodies, in English and Portuguese as well as Spanish.

Attached as an annex to the CEA Code are Model Arbitration Rules, which incorporate the guidelines of the Code stating, "All persons participating in the arbitration proceedings … undertake to perform their functions in accordance with the Code of Best Practices of the Club Español del Arbitraje (2019)." Rule 27.6. Together, the Code and the Rules refer to the roles and duties of all participants in the arbitration process—including arbitral institutions and their rules, arbitrators, lawyers and expert witnesses as well as tribunal secretaries and third-party funders. The Code and Rules may be found Kluwer Arbitration Blog, José Antonio Caínzos, "The Madrid International Arbitration Centre Takes Off Powered by the Unification of Spain's Largest Arbitral Institutions" (Dec. 14 2019). We examine below some of the more innovative ways the Code and Rules deal with various of the participants.

Arbitral Institutions

The Code recognizes that arbitral institutions "play a fundamental role in the promotion, performance and legitimacy of arbitration," acting both as service providers and "ensuring due process and the fairness of awards," reminiscent of the way that stock exchanges have both facilitated trading and regulated their members' conduct. The organizational model posited by the Code is essentially that of the International Chamber of Commerce, with provision for governance through a "court" assisted by a general secretariat as a "management body." With respect to the conduct of arbitral proceedings, the model institution would require, as does the ICC, that all estimated costs of a proceeding be paid in advance (in contrast to the AAA's assessing of arbitrator costs as the arbitration proceeds), terms of reference (Rule 30) and for scrutiny of awards before they are transmitted to the parties (Rule 49).

A major difference, however, between the Code's recommendations and the ICC is transparency. The Code's arbitral institution would have a website that would hold back no pertinent information about the institution from users or the public, setting out, among other things, (1) details on its entire organization, including "annual accounts and the management reports" for the previous five years, (2) the names of any persons who sponsor conferences or events organized by the institution, and the amounts paid by such sponsors for the previous five years, and (3) "detailed statistics on the matters it administers and on arbitrator appointments, broken down by age, gender and origin." Para. 5.1.

The Code recommends that institutions not keep a list of arbitrators, but, if they do, make the list public, open and non-binding and reviewed each year, with reasoned decisions for the rejection of any persons from the list. The Code also pushes arbitral institutions into not keeping case information confidential, urging the publication on the institution's webpage of a list of the cases administered by it, indicating the names of the arbitrators and administrative secretaries, the parties' lawyers, how the arbitrators were appointed, dates of important events in the arbitration, and, after the award is rendered, if its content is not public, the "reasons for its confidentiality." Only the parties are not to be identified, other than by an "anonymized reference" to their "nature." Awards are to be published "within a brief period following their approval," with anonymized party names. If a party "expressly objects" regarding lack of confidentiality and the institution "considers that there are relevant grounds justifying confidentiality" only an "anonymized summary or a redacted extract of such awards" will be disclosed.

Notwithstanding this transparency, the Code and Rules impose duties of confidentiality not only on the court and the arbitrators but also on the lawyers, purporting to prevent them, even in the absence of a confidentiality agreement and without time limit, to keep confidential "any information that they acquire in the arbitration proceedings," including the parties' submissions, the evidence presented, any settlement agreement and decisions by the arbitrators including the award. Although this guideline would serve the salutary purpose of preventing lawyers from writing about arbitrations in which they are participating while they are going on, some lawyers may not be happy with such an institutional imposition of confidentiality on them, notwithstanding the absence of confidential stipulations by the parties. They may want, for example, to make use of portions of an expert's report for cross-examination in other proceedings. The Code contains no such restriction with respect to disclosure by parties.

Witnesses

Contrary to the practice in some civil-law-based proceedings such as the Iran-US Claims Tribunal, the Code accords the same treatment as witnesses to both party representatives and non-parties who present evidence regarding issues of fact. The Code provides that lawyers may interview potential witnesses "for the purpose of preparing their testimony …," making it clear that restrictions on such contacts that may exist in certain national courts do not apply.

The Rules pay no specific attention to the role of cross-examination in international arbitration hearings, although by recognizing that witnesses may present their evidence through written statements (as is commonly done) the Rules impliedly recognize that under such circumstances cross-examination may be the only oral testimony that arbitrators receive. How cross-examination or other questioning of witnesses may be carried out is dealt with in Rule 38.4, which provides generally that all parties may "ask the witnesses any questions that they see fit, under the control of the arbitrators," who are to have regard to the "relevance and usefulness thereof." Counsel planning to challenge the testimony of witnesses in proceedings under this Rule will have to consider the extent to which their questions may be regarded by the tribunal as "useful."

Expert Witnesses

Expert witnesses are given more extensive treatment in both the Code and the Rules, which emphasize their duties of objectivity and independence. The Code provides that experts "maintain an objective distance from the appointing party, the dispute and other persons involved in the arbitration." Para. 134. It is not clear what keeping an "objective distance" means for purposes of preparing an expert witness to testify. Moreover, it is unclear how maintaining an objective distance comports with Guideline 20 of the IBA Guidelines on Party Representation, which permits "party representatives" (lawyers) to "assist … Experts in the preparation of expert reports."

The Code sets out questions that prospective expert witnesses should consider in complying with their obligation under Rule 39 to "disclose any circumstance that may give rise to justifiable doubts as to their objectivity and independence." One such question that may give rise to concern on the part of lawyers who frequently rely on the same expert is the following: "In the last 10 years, have you personally acted as an expert in another proceeding upon appointment by the same lawyer or law firm that has appointed you in the present arbitration?" Para. 145.11. The possibility that such a relationship may be the basis for disqualification of an expert may give rise to apprehension on the part of counsel who have had continuing relationships with certain experts, such as damages experts.

Tribunal Secretaries

In virtually identical language, the Code and the Rules impose limitations on the role to be played by persons who serve an arbitral tribunal in an administrative capacity. The secretary is made subject to the same duties of disclosure and independence as arbitrators and is restricted to "perform[ing] certain tasks of an administrative, organisational or supporting nature" and is not to have delegated to him or her "any decision-making or evaluative role concerning the positions of the parties in fact or in law." Code, paras. 95 and 97 and Rule 17. The secretary is to be appointed by a sole arbitrator or the chairman of a three-person panel and is to be remunerated "directly by the president or the sole arbitrator from the latter's own fees." Any other system of remuneration must be agreed to among the parties and the arbitrators prior to their appointments.

No other institution has so directly dealt with the common practice of tribunals, particularly in Europe, to make use of additional persons in carrying out their responsibilities as arbitrators. But how the restrictions are to be enforced is left unclear. Some teeth would be put into these rules if the arbitral institution required descriptive time reporting by arbitrators and secretaries. It is also possible that allegations of violations by the arbitrators of the institution's limitations on secretaries' activities, might, if alleged to have had an adverse effect on an arbitral award, give rise to challenges by a losing party to enforcement of the award.

Third-Party Funders

The Code and the Rules, as well as the introduction to them, reflect a skepticism about the effect of third-party funding on arbitration. The introduction states vaguely that third-party funding "poses new questions which if not appropriately addressed could have a negative impact on how arbitration is generally perceived." The Code and Rules impose requirements that, the introduction says, have one "pivotal idea," protecting the "independence and impartiality of the arbitrators." The Rules do so by requiring disclosure to the arbitrators of the existence of such funding and the identity of the funder "as soon as the funding occurs." Rule 25.1 The Code imposes the more limited requirement that the disclosure be limited to funding that "is linked to the outcome of the arbitration." The Code requires that disclosure be made no later than in the statement of claim or within a "reasonable period" if the funding occurs thereafter. Para. 154. Both provisions permit arbitrators to require the funded party to disclose "additional information that be relevant," although the requested party may suppress certain information, in particular, "the financial conditions of the transaction." Para. 156. The Rules do not contain this limitation.

These requirements can be seen to reflect concern about potential conflicts of interest on the part of arbitrators who as practitioners may have had recourse to the same funders as those used by a party. The provisions do not deal with how any such conflicts are to be dealt with nor do they address whether the information that might be obtained might also be used for the purpose of ascertaining whether the funding might include protection against an award of costs or a requirement for payment of security for costs. The introduction intimates that the provisions regarding funding may later be "broadened" and that the limitation to disclosure of "the existence and identity of the funder" is for "at least for the time being." Should the provisions be adopted in final form, they may include clarification of the concerns underlying the funding disclosure requirements.

Conclusion

Although there is an undeniable Spanish and Latin American background to the CEA Code and Rules, there is nothing limited or parochial about what the Spanish Arbitration Club has produced—a codification of what could be an advance indication of new and different practices that will be adopted elsewhere in the world over the course of the new decade.

Lawrence W. Newman is of counsel and David Zaslowsky is a partner in the New York office of Baker McKenzie. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Judgment of Partition and Sale Vacated for Failure To Comply With Heirs Act: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Artificial Wisdom or Automated Folly? Practical Considerations for Arbitration Practitioners to Address the AI Conundrum

9 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Fresh lawsuit hits Oregon city at the heart of Supreme Court ruling on homeless encampments

- 2Ex-Kline & Specter Associate Drops Lawsuit Against the Firm

- 3Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

- 4The Importance of Federal Rule of Evidence 502 and Its Impact on Privilege

- 5What’s at Stake in Supreme Court Case Over Religious Charter School?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250