Marty Tankleff, Decade-Plus After Murder Conviction Overturned, Becomes a Lawyer

"I think from an exonerree's point of view, we face one challenge after another, from trying to prove our innocence, to trial, to the appeals, even in the post-wrongful conviction process," said Tankleff in an interview. He was buoyant on Wednesday about becoming a New York lawyer.

February 06, 2020 at 11:15 AM

7 minute read

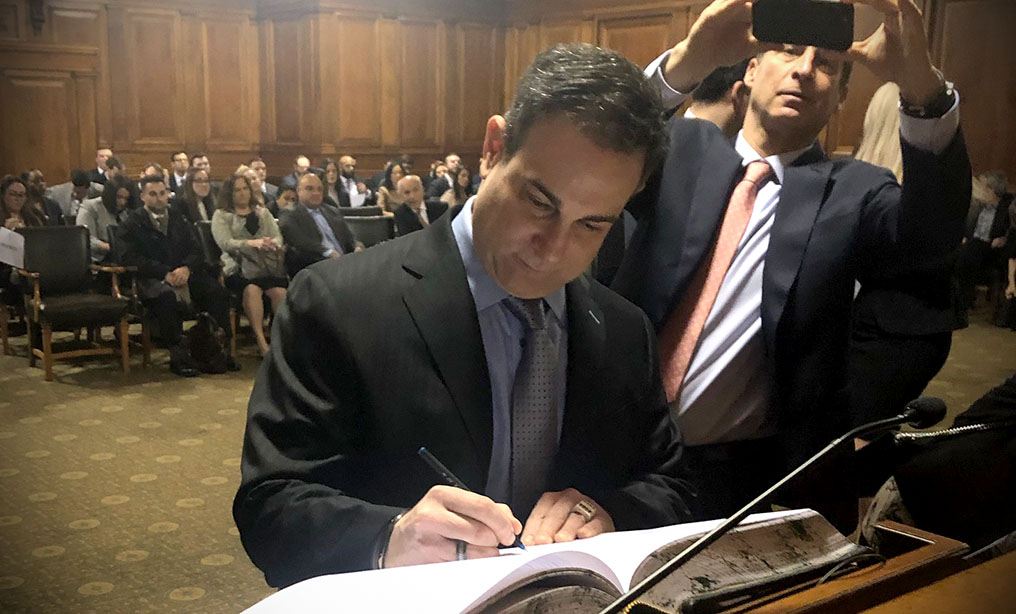

Marty Tankleff's swearing in on Wednesday, Feb. 6. (Courtesy photo)

Marty Tankleff's swearing in on Wednesday, Feb. 6. (Courtesy photo)

When Martin Tankleff stepped forward Wednesday to sign the attorney roll book, just minutes after being sworn in as a newly minted lawyer in New York, he met eyes for a moment, he says, with one of the Appellate Division, Second Department justices who had voted in 2007 to overturn his wrongful murder conviction.

"One of the judges from the [2007 appellate] panel was almost directly in front of me, and we looked at each other, sort of recognizing how significant this day is," Tankleff said in a phone interview with the New York Law Journal on Wednesday, just hours after he became a lawyer, fulfilling a dream and a calling that he says began during the 17 years he spent in state prison for allegedly murdering his parents.

The judge, Justice Mark Dillon, was part of the four-judge panel that had heard arguments in Tankleff's appeal, both men sitting inside the same ornate Brooklyn courtroom that on Wednesday became the setting for Tankleff's and many other lawyers' swearings-in.

The symbolism and significance of Wednesday's event, after Tankleff had spent years fighting for his freedom—before reentering society to become a law clerk, a law professor and a public speaker calling out the ills of wrongful convictions—was not lost on Tankleff.

Just after being sworn in Wednesday, "I just looked at my wife and my daughter and I mouthed, 'Thank you,'" Tankleff told the Law Journal.

He added, "It was a long time coming, but with their help, I was able to overcome everything."

By everything, said Tankleff, who was convicted at age 19, he meant the entire fight throughout half of his life, from his wrongful conviction legal and psychological battles to his efforts in recent years to become a lawyer. The work he put in to make it to Wednesday's lawyer ceremony included taking the bar exam several times and then spending more than two years, from 2017 to 2019, attempting to pass the Second Department character and fitness committee's inquiries and vetting process of him.

Now, according to Tankleff, he is excited to be able appear in court and represent clients. A member of the bar at age 48, he can take a more integral and out-front role as he advocates in the types of wrongful-conviction cases that he's been involved in almost since winning his freedom.

"On Thursday morning, if I appear in Suffolk County court," where he lives, "it will be Martin Tankleff for the defense," Tankleff said in phone interview earlier this week.

"To me, who better to advocate for someone who is potentially wrongfully convicted than somebody who's been there?" he added, his voice rising.

Tankleff's long-term goal, he said, is to model his career after some of the leading wrongful conviction attorneys in the nation, like those who helped him pro bono throughout his legal appeals in the 1990s and 2000s. They included Stephen Braga, a partner at Bracewell, Bruce Barket of Barket Epstein and Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project.

"I think from an exoneree's point of view, we face one challenge after another, from trying to prove our innocence, to trial, to the appeals, even in the post-wrongful conviction process," Tankleff said. He added, "I think people need to understand that we have a [criminal justice] system that is flawed, and exonerations can take luck, skill and time. They are not done on technicalities."

By referencing the "post-wrongful conviction process," Tankleff, in one respect, was pointing to the fight he had waged himself in recent years as the Second Department's character and fitness committee, to his surprise, decided that he would not be approved quickly, as are most applicants.

After passing the bar exam in 2017, Tankleff thought the final leg of the admission process would go smoothly. His life and case, after all, he points out, has been publicized in media far and wide. He was 17 when his wealthy parents were discovered stabbed and beaten to death in Suffolk County, and he was quickly arrested. In 1990, he was convicted at trial, according to news reports, based in large part on a police station house confession that he'd repudiated almost right away and never signed. Then in 2007, an appellate panel overturned his conviction, citing the Suffolk County trial judge's failure to properly consider new evidence put forward by his lawyers. The state decided not to retry Tankleff, according to reports, and later he received more than $10 million in settlements from Suffolk County and New York state.

Still, in 2018, according to Tankleff, he got a letter from the character and fitness committee saying that he would need to attend a hearing on his application, and that he was not yet approved.

Both Tankleff and the lawyer he hired to represent him before the committee, Barry Kamins, an Aidala Bertuna & Kamins partner and a former state Supreme Court justice, say today that, pursuant to state judiciary law, they can't reveal what the committee's issues or questions were. However, they also both made clear that Tankleff's fitness examination included multiple hearings, calling witnesses to the stand, and submitting a raft of documents.

In the end, said Kamins, Tankleff was approved by both the committee and the Second Department court. And the process, he said in an interview, amounted to another hurdle and travail that Tankleff surmounted.

"This was a very unusual process," said Kamins. "We had to satisfy the questions that the committee had, and it added to the challenges he's had to overcome over the years. But, as always, he remained very positive."

For his part, Tankleff said this week that the character and fitness hurdle surprised him and, to a degree, disappointed him.

"The issues that were raised were shocking, because they really weren't issues," he said. "If you look at the facts and the law and the question presented, everything was in my favor."

On Wednesday, the Second Department's Committee on Character and Fitness referred all questions about Tankleff and his review process to the Second Department clerk's office. The court clerk, in turn, cited Judiciary Law 90[10] and said that "the admission process is confidential by law" and "therefore I am not at liberty to provide you with the answers you seek."

By late Wednesday, after the swearing-in, the process and hurdles that had come before seemed to be the last thing on Tankleff's mind. He sounded buoyant and proud to be joining the state's collection of lawyers. And in interviews earlier this week, he was intent on underlining that he was ready to follow in the footsteps of the wrongful conviction-focused attorneys who have become his role models and heroes.

"As Bruce Barket has said, this kind of legal work is doing God's work, in the sense that you are trying to save someone's life or get their life back," he said.

"It's the most empowering work and the most emotional work you will do," he added.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Lawyers Across Political Spectrum Launch Public Interest Team to Litigate Against Antisemitism

4 minute read

'A Shock to the System’: Some Government Attorneys Are Forced Out, While Others Weigh Job Options

7 minute read

Haynes and Boone Expands in New York With 7-Lawyer Seward & Kissel Fund Finance, Securitization Team

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Parties’ Reservation of Rights Defeats Attempt to Enforce Settlement in Principle

- 2ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 3States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 4Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 5Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250