It's Not Just About Mediation: 'Presumptive ADR' and the Spectrum

The spectrum is a visual representation of all of the dispute resolution processes from negotiation through and including litigation. This article is meant to provide a brief overview of processes on the spectrum, other than mediation, that the courts may be employing.

March 13, 2020 at 02:40 PM

9 minute read

Claudia Lanzetta

Claudia Lanzetta

In an article first published in the New York Law Journal and then reprinted in the Queens County Bar Bulletin, the ADR process of mediation was discussed at length in the context of the court system's launch of the progressive "Presumptive ADR" program. Claudia Lanzetta, "Be Prepared: 'Presumptive ADR' is Coming. The Importance of Being Proficient in Mediation," NYLJ (Aug. 5, 2019). Following the first publication, various Queens County bar associations combined forces to host a Presumptive ADR discussion, featuring Deputy Chief Administrative Judge George J. Silver and Administrative Judge of the Civil Courts of the City of New York Anthony Cannataro. During that presentation, the ADR spectrum was discussed.

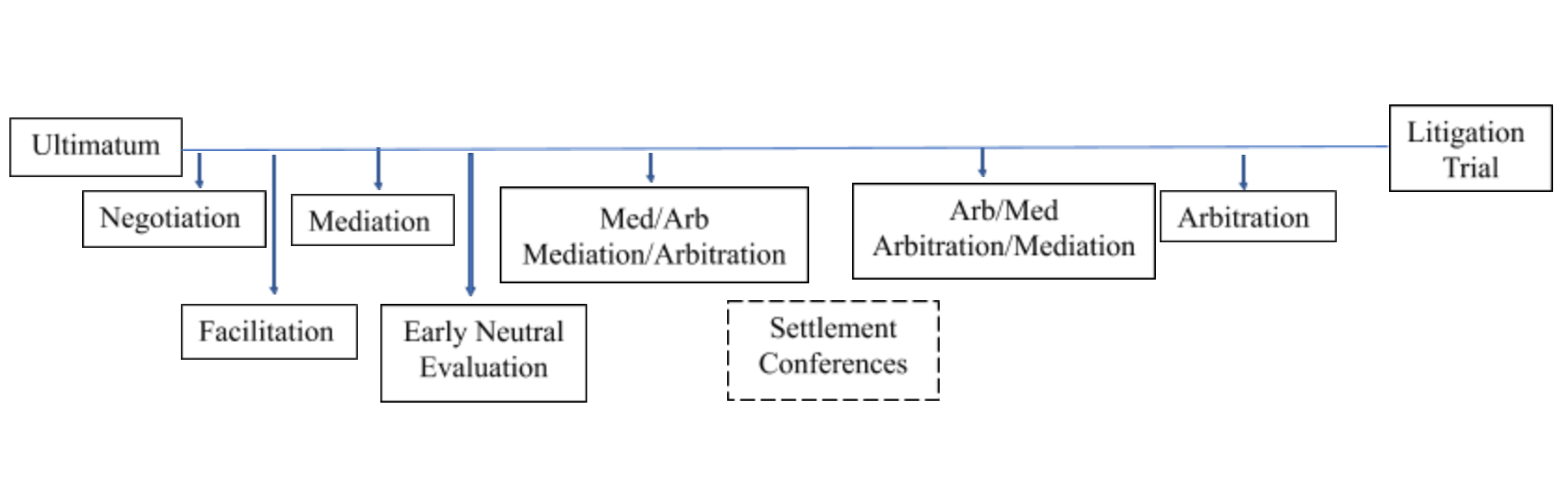

The spectrum is a visual representation of all of the dispute resolution processes from negotiation through and including litigation. As you move from left to right, the processes move from consensual to adjudicative and from informal to formal. Also, at the far left the parties determine the outcome and retain control whereas at the far right a third party decides for them and they cede control. This article is meant to provide a brief overview of processes on the spectrum, other than mediation, that the courts may be employing.

The spectrum, in a slightly amended version, appears as follows:

The amendment is the addition of settlement conferences. Judicial settlement conferences that do not traditionally appear on the spectrum arguably have a place thereon. Their use, both on a case-by-case basis and as "blockbusters" for classes of cases, has been discussed in conjunction with the Presumptive ADR initiative. Given the characteristics of this process, placement on the spectrum is somewhat problematic. On the one hand, the process is overseen by an adjudicative figure and occurs in the context of litigation, favoring placement towards the right end of the spectrum. On the other hand, the parties maintain ultimate control over the decision to accept or reject the settlement offer, favoring placement at the left end. For the present purposes this process appears as a floater somewhere in the middle of the spectrum (as above).

Settlement conferences should have a spot on the spectrum in recognition of the statistical likelihood that a case will not proceed through trial and this process lends itself to early resolution. This understanding is one of the driving forces behind Presumptive ADR, which is being implemented, in part, to eliminate case backlogs. To that end, settlement conferences, although definitionally not Presumptive ADR, serve this purpose. It should be highlighted that settlement conferences are not a form of mediation. Mediation, as discussed in the prior article, is a distinct ADR process that has unique characteristics. While settlement conferences utilize a neutral third party to facilitate negotiation they do not touch upon all that mediation can and is intended to.

Settlement conferences in the context of individual matters or classes of cases serve the singular purpose of arriving at terms agreeable to all parties that work to dispose of the case before the court. Generally, the terms are a monetary figure that neither party is wholly satisfied with. The third party neutral, often a judge, is truly a facilitator. The judge conveys demands, offers and counteroffers while presenting the realities and uncertainties of proceeding to trial. This often occurs in a trial scheduling part before the attorneys are sent out to pick a jury, or in a trial part at a pre-trial conference prior to the start of voir dire. In engaging in this process, parties customarily favor settlement and the goal of reducing backlog is served.

Another process that the Civil Courts are employing with greater fervor is Early Neutral Evaluation. In its simplest definition this process offers litigants a "reality check" as to the merits of their case. Early Neutral Evaluation utilizes attorneys, either acting on their own or in panels of three, to assess the value of a case before trial. These attorney-evaluators hear shortened case presentations. They can consider documentary or witness evidence and can entertain arguments. The resulting evaluation, which is advisory and non-binding, may suggest the strengths and/or weaknesses in a case, or may predict a likely monetary verdict. Evaluations can then be used to facilitate negotiations towards settlement. Should negotiations fail and a settlement is not reached the attorney-evaluators may assist the litigants with other case relative matters, such as developing and overseeing a discovery schedule and narrowing issues for trial. Early Neutral Evaluation is a useful tool in maintaining a light docket especially given its purpose of addressing cases in their initial stages (see generally Carrie J. Menkel-Meadow, Lela Porter Love, et. al. Dispute Resolution, Beyond the Adversarial Model, [2nd Ed. 2011]).

The spectrum also provides a place for two processes, the use of which is unknown with respect to the Presumptive ADR program: Meditation/Arbitration and Arbitration/Mediation, also known as Med/Arb and Arb/Med, that combine the individually named processes into these hybrid variations. When parties engage in Med/Arb they attend mediation sessions followed by arbitration if they fail to reach an agreement in the former process. In the reverse variation, Arb/Med, an arbitrator hears the parties' presentations, often makes a sealed award, and then attempts to mediate the dispute. If the latter facilitated negotiation fails to result in settlement the arbitrator will then release his/her award. In these hybrids either two independent neutrals can be used to preside over the different processes, or one neutral who switches roles may oversee the entire process. It is said that combining mediation and arbitration blends the best characteristics of each process. The speed, efficiency and consensual aspects of mediation join with the efficient finality of arbitration. The hybrids Med/Arb and Arb/Med can offer additional resources in the Presumptive ADR reservoir of trial alternatives and settlement facilitators.

Finally on the spectrum preceding formal trial is the process of arbitration. Again, its use in connection with Presumptive ADR is unexplored. Arbitration enjoys some familiarity among attorneys as an informal process where a neutral third party not acting as a judge renders a decision in a dispute. However, most practitioners are unaware of the processes' variants and the flexibility in their application. That flexibility is a key attraction and benefit of the process. The nature of arbitration varies depending on the subject matter of the dispute, as well as the choices of the participants. Arbitration can be binding or non-binding. It can be voluntary, contractual or statutory. It can be more or less formal, and similarly costly or inexpensive. The process can be presided over, and the decision made by a single arbitrator or a panel of arbitrators.

Binding arbitration is as it sounds—final and binding on the disputants. Although it is subject to limited judicial review (see CPLR Articles 75 and 78), that review often fails to vacate an arbitral award. In contrast, non-binding awards can be advisory opinions. Voluntarily accepted by the disputants or left unchallenged, however, these awards become binding. Finality is therefore achieved in either variation. Arbitration can differ according to its source and time of origin. Pre-dispute arbitration agreements or contracts comprise the majority basis for arbitration proceedings. These agreements can be knowingly negotiated or imposed in a nonnegotiable contract. (The validity of the latter is often a threshold issue.) Alternatively, some arbitration is mandated by a statute, court rule, or treaty. These variations exist prior to any dispute in controversy. Arbitration can also arise when the dispute does, and the parties choose to engage in the process. This type of arbitration can be labeled voluntary.

In some proceedings, a single arbitrator can be used, while in others a panel of three or more arbitrators preside. A benefit of either is that the arbitrators are often chosen because of their expertise and experience in a particular field of law. In addition to the choices surrounding the presiding arbitrators and their appropriate role, the disputants can also determine their own rules of procedure and evidence, thereby setting the stage for the formality, or informality of the proceeding, as well as the related expense. Finally, arbitration, like many of the ADR processes, is private in both the proceedings and the awards, unless publicized by the disputants.

The goal of this and the prior article is to impart a basic understanding of the various ADR processes in light of the court's initiative. ADR as a discipline is expansive and its utility exploding. The undeniable reality is that a small percentage of cases commenced actually proceed through to trial and verdict. In recognition thereof, the ADR processes, including judicial settlement conferences, offer an efficient and conscientious way of resolving disputes. For the practitioners, it is therefore crucial to have a working knowledge of all the ADR possibilities. Most significantly, ADR is a discipline that promotes "fitting the forum to the fuss", (see Frank E.A. Sander and Stephen P. Goldberg, Fitting the Forum to the Fuss: A User-Friendly Guide to Selecting an ADR Procedure, 10 Negot. J. 49 (1984)), or assigning the proper resolution process to the dispute. Knowledge of the ADR processes in conjunction with the court's Presumptive ADR initiative would serve that purpose and promote success of the court's plan.

Claudia Lanzetta, a Judge of the Civil Court, received her LL.M. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in May 2018 in alternative dispute resolution and advocacy.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: Trial Court's Sidestep of 'Batson' Deprived Defendant of Challenge to Jury Discrimination

Decision of the Day: Commercial Division Finds Defendant Engaged in Unfair Competition Against Plaintiff

Decision of the Day: Court Rules on Judgment Motions Over Police Killing of Pet Dog While Executing Warrant

Decision of the Day: JFK to Paris Stowaway's Bail Revocation Explained

Trending Stories

- 1Delaware Supreme Court Names Civil Litigator to Serve as New Chief Disciplinary Counsel

- 2Inside Track: Why Relentless Self-Promoters Need Not Apply for GC Posts

- 3Fresh lawsuit hits Oregon city at the heart of Supreme Court ruling on homeless encampments

- 4Ex-Kline & Specter Associate Drops Lawsuit Against the Firm

- 5Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250