State Bar Proposes Cash, Education and Tech to Support New York's Rural Lawyers

A task force is calling on law schools, the state government and the legal industry to do more to increase access to justice in rural communities.

March 19, 2020 at 05:00 AM

5 minute read

Scott Clippinger outside his office in Chenango County, where there aren't enough lawyers to meet the needs of clients. Photo: Margaret Brenner

Scott Clippinger outside his office in Chenango County, where there aren't enough lawyers to meet the needs of clients. Photo: Margaret Brenner

The number of lawyers in rural parts of New York is small—and at risk of falling further.

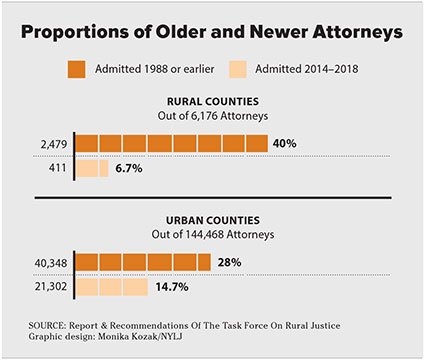

Even though New York has more lawyers than every other state, roughly 96% of attorneys practice in metropolitan areas, with the remaining 4% serving New York's more rural parts, according to the New York State Bar Association research. And nearly 75% of current rural practitioners will be retiring in the next 10-30 years, with little to no new attorneys filling their place.

Now the New York State Bar Association is calling for major steps to stem the tide, including the creation of a $22,000 annual grant for new lawyers who serve rural communities.

Taking inspiration from states such as South Dakota and Nebraska, the state bar's Task Force on Rural Justice called on law schools, the state government and the legal industry to do more to increase access to justice in rural communities, according to a report to be released Thursday.

With a handful of graying solo general practitioners often the only lawyers for miles around, the task force called for funds to be allocated, law student recruitment and curricula to be changed, and for the state court system to make it less costly to litigate, among other proposed fixes.

One of the top recommendations was a state-funded grant program that would help seven new lawyers per year handle their living expenses in exchange for a commitment to practice in an area with relatively few lawyers. Alternatively, the state bar called for new funds to be applied exclusively to student loan repayment assistance for new rural lawyers, or for existing tuition and loan repayment assistance programs to be expanded.

Some of the proposals would require funding or other action by New York's state legislature. For instance, as the task force recommends, the legislature would have to fund higher 18-b payments and the program to subsidize new rural lawyers. It would also need to sign off on higher dollar limits for small-claims cases in town and village courts—the report proposes raising them from $3,000 to $7,500—and on changes to the public officers' law to give under-lawyered political subdivisions more flexibility to recruit justices, prosecutors and public defenders who don't reside in them.

Some of the proposals would require funding or other action by New York's state legislature. For instance, as the task force recommends, the legislature would have to fund higher 18-b payments and the program to subsidize new rural lawyers. It would also need to sign off on higher dollar limits for small-claims cases in town and village courts—the report proposes raising them from $3,000 to $7,500—and on changes to the public officers' law to give under-lawyered political subdivisions more flexibility to recruit justices, prosecutors and public defenders who don't reside in them.

But some changes could be made administratively or by the private sector. The state court system could make the rules governing part-time judges less strict in a way that would encourage more lawyers to take up such roles, a proposal supported by a majority of the task force.

Other proposals call for expanding e-filing to town and village courts, as well as expanding broadband access. Despite spending hundreds of millions of dollars, the report noted, New York State still has areas where slow satellite connections are common.

The co-chairs of the task force, Justice Stan Pritzker of the Appellate Division, Third Department and Taier Perlman, a staff attorney with Legal Services of the Hudson Valley, said action is needed now.

"This package of proposals we came up with is based on a very expansive study of what other jurisdictions are doing," Perlman said. There are social, political and economic forces that are leading to the rural decline "and we can't tackle all of them," Perlman said, but "the interventions really focus on the things we think will make an impact on practitioners in rural New York."

Meanwhile, law schools can do a better job of building a pipeline to support rural communities, the report said. While some pro bono efforts, like the "Justice Bus" program run out of Buffalo and the Farmworkers Clinic at Cornell, provide direct support to the poor and disabled in rural parts of the state, many law students graduate with little practical knowledge of running a rural law practice, the task force wrote.

The report notes that some professors and law school staff associate prestige with urban law firms that represent institutions rather than people, but there is untapped interest—particularly among students with rural roots—in rural practice. Perlman said a panel put on by Albany Law School about running a rural practice drew "incredible turnout." Other measures, like mentorship programs with law students and rural practitioners or summer internships with rural law firms or judges in rural courthouses, could also help, she said.

"Anything that'll expose the student to what rural practice is like is a good thing, and I think that's not a heavy lift," she said. The state bar is already working toward growing its support of rural practitioners approaching retirement and who are unsure of how to transfer and wind down their practice, she added.

Hank Greenberg, the state bar's president, said he was proud of the task force's work and said the judiciary and legislature are receptive to suggestions for improving access to justice in rural areas. While he said proposals that require funding might be a tough sell because of the state's current deficit that will likely be worsened by the coronavirus pandemic, he said he hoped a solution could be found in the 2021 legislative session.

"There are more than one million people that live in rural New York," he said. "Increasingly, they have no lawyers to turn to."

Read More:

Lawyers Retire, Move Out of Rural Upstate NY at Alarming Pace

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Alston & Bird Adds M&A, Private Equity Team From McDermott in New York

4 minute read

Weil Lures DOJ Antitrust Lawyer, As Government Lateral Moves Pick Up Before Inauguration Day

5 minute read

Trending Stories

- 1In-House Lawyers Are Focused on Employment and Cybersecurity Disputes, But Looking Out for Conflict Over AI

- 2A Simple 'Trial Lawyer' Goes to the Supreme Court

- 3Clifford Chance Adds Skadden Rainmaker in London

- 4Latham, Kirkland and Paul Weiss Climb UK M&A Rankings

- 5Goodwin Hires Quinn Emanuel Partner to Launch Office in Brussels

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250