Have Confidence in Our Legal Profession, Courts and Future

The current coronavirus will be beaten—either by time, warmer weather, precautionary measures, medical science, or likely a combination of all of the foregoing. Law practices and courts will get through this.

March 20, 2020 at 02:35 PM

5 minute read

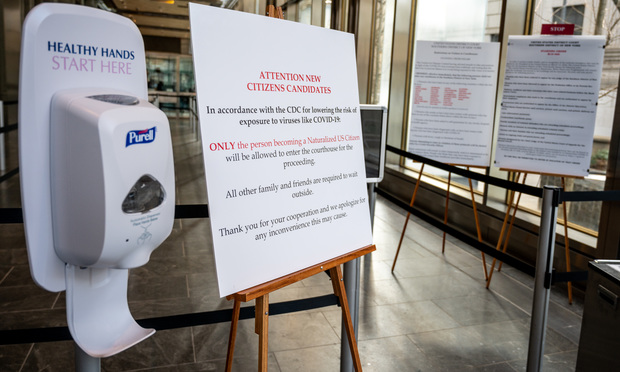

Purell and a sign listing visitors who may not enter at the entry to the courthouse. Photo: Ryland West/ALM

Purell and a sign listing visitors who may not enter at the entry to the courthouse. Photo: Ryland West/ALM

I share with my friends and colleagues an observation about the effect of the coronavirus upon the bench and bar of our state. As attorneys and judges, we are invested in serving the public, representing and advising clients in need, interacting with courts, mediators and arbitrators, and upholding the highest ethical standards in the process. It is painful for all of us to witness public health circumstances beyond our control that keep potential clients from signing retainer agreements or from interacting face-to-face with counsel, recent law school graduates entering into a now-uncertain job market, and attorneys unable to attend conferences, argue motions, try cases, and otherwise appear in courts that have essentially shut down but for limited emergency matters.

This is not the first time our profession has encountered significant difficulties. The following history is recounted in the hope that it provides us with a sense of longer-term confidence in our noble and necessary profession, and in our futures.

In May 1765, the British Parliament enacted the Stamp Act, which required that special stamps be purchased for all legal papers, shipping documents, almanacs, playing cards, and even dice. John M. Blum et al., The National Experience: A History of the United States (4th ed.), 85. (New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1977). The Stamp Act was to become effective on Nov. 1, 1765, meaning that the colonists had roughly six months to agitate against the measure before its implementation. The Stamp Act was controversial because it was the first time that Britain sought to impose a tax that was purely "internal" to the colonies, as distinguished from taxes imposed on external trade between the colonies and Europe. There were demonstrations, mobs, riots, property damage, and confrontations between large crowds and British troops. Walter Stahr, John Jay: Founding Father, 22 (New York: Diversion Books, 2005). The coach of New York Governor Cadwallader Colden, an appointee of the King, was seized, smashed, and burned at Bowling Green. F.L. Engelman, "Cadwallader Colden and the New York Stamp Act Riots," 572. 10 William & Mary Quarterly 560 (Spring 1953). In response to the uprisings, the stamps were not distributed throughout the New York colony, which had the effect of forcing the courts to close. Herbert Alan Johnson, "John Jay: Lawyer in a Time of Transition, 1764-1775" 1267. 126 Univ. of Pennsylvania Law Review 1260 (May 1976). Without courts and legally-stamped papers, law offices closed as well, and legal matters ground to a halt until the Stamp Act was repealed. At the time, the New York bar was so small that from 1709 to 1776, only 136 attorneys were licensed to practice law in the New York colony, and of those, only 41 practiced in what we now know as New York City between 1695 and 1769. Anton-Hermann Chroust, "Legal Profession in Colonial America," 33 Notre Dame Law Review 350 (1958). The time that law offices were closed were lean times for New York attorneys, for reasons that, like now, were beyond their control. Then, there were no telephones, email, and Skype or Zoom platforms to enable the practicing bar to electronically continue some semblance of the daily profession. There simply was little profession during that time to practice.

When the Stamp Act was repealed several painful months later, in March 1766, the Bar found that there was a pent-up demand for its legal services. Blum et al., "The National Experience," supra. There was much overdue legal work to be performed. The legal profession burst forward. Courts re-opened and attorneys and judges were busier than ever.

The current coronavirus will be beaten—either by time, warmer weather, precautionary measures, medical science, or likely a combination of all of the foregoing. Law practices and courts will get through this, just as our predecessors did during the lean times of 1765-66. And we will find that at the back end of this health crisis, there will be a overdue need for attorneys, judges, mediators, referees, arbitrators, fact witnesses, experts, court clerks, law secretaries, court officers, process servers, stenographers, claims adjusters, Law Journal reporters, and law professors—all of the people that we know, encounter, and admire in our collective profession—to meet the demand that is coming for legal services as our profession and courts roar back to where we were as recently as February 2020. There may be additional stories about our profession weathering the burning of the White House in 1814, the Civil War, a flu epidemic that infected one-third of the world population in 1918 (1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus), U.S. Center for Disease Control), two World Wars, a Great Depression in the 1930s, the killing of national leaders, the struggle for racial and gender equality, and the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, which lay on the same bookshelves as the history of our predecessors during the months that the Stamp Act controversy caused so much disruption and economic distress.

Our profession will be okay. I feel it in my 60-year-old bones, and urge you to feel the same.

Mark C. Dillon is a Justice of the Appellate Division, Second Department, an adjunct professor of New York Practice at Fordham Law School, and a contributing author to the CPLR Practice Commentaries in McKinney's.

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Attorney Responds to Outten & Golden Managing Partner's Letter on Dropped Client

3 minute read

Letter to the Editor: Law Journal Used Misleading Photo for Article on Election Observers

1 minute read

NYC's Administrative Court's to Publish Some Rulings in the New York Law Journal Is Welcomed. But It Should Go Further

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 2States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 3Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 4Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 5Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250