The Right Thing To Do

We live in a dark time, and we all need heroes. John Feerick is my hero. If you read this book, he will be yours.

May 12, 2020 at 10:30 AM

10 minute read

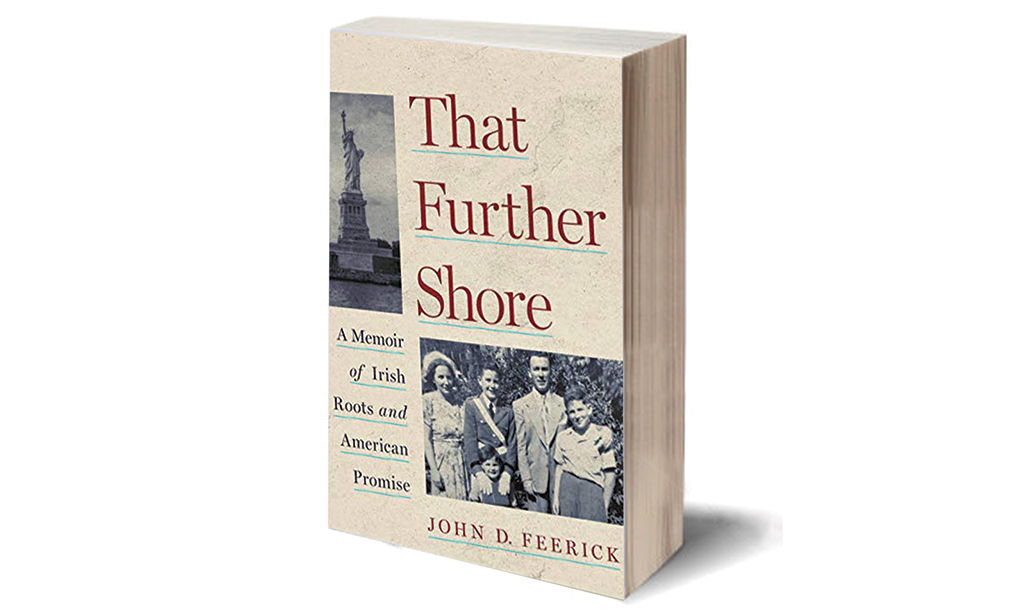

"That Further Shore: A Memoir of Irish Roots and American Promise," by John D. Feerick

"That Further Shore: A Memoir of Irish Roots and American Promise," by John D. Feerick

Fordham University Press, 2020

456 pages, $34.95

John Feerick has had one of the most remarkable legal careers of our time, dizzying in its scope and achievement. He is both the drafter of a constitutional amendment and a central figure in one of the most famous chapters in the history of basketball. He played an important role in building a great law firm, and he served for two decades as one of the nation's most revered law school deans. He is a beloved teacher and an acclaimed scholar, a fighter for reform in both New York City and State, a leader of the Bar, a champion of peace in Northern Ireland, an important lay figure in the Catholic Church in New York, and a crusader for the most vulnerable in our society. And he has now produced a capstone: an autobiography that, at this most terrible time, gives us an opportunity to reflect on how to live a life and what truly matters.

In reading this wonderful autobiography, I thought back to when I first met John. We met when he became chair of the New York State Commission on Government Integrity in 1987. I will start this review with that story because, although his role as chair is only one part of John's fascinating story, it illustrates who is he is and why we all can learn from reflecting on his life and commitments.

New York City in the late 1980s was confronting one of its great corruption scandals. Pay-offs in the Parking Violations Bureau came to light, the powerful Queens Borough President Donald Manes committed suicide, and larger than life figures—including Mayor Ed Koch, a young Rudy Giuliani, and iconic journalist Jimmy Breslin—fought. It was compelling drama. Indeed, it became the subject of the first episode of the TV show Law and Order.

Gov. Mario Cuomo created a Commission on Government Integrity to investigate and to recommend reforms, and I was one of its first employees. When John was named chair, we all eagerly researched his background, and we were amazed (and humbled) by his record of achievement.

John had started his legal career with great distinction at Fordham Law, where he had been editor-in-chief of the law review. His law review scholarship about presidential succession led him, in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, to become a central figure in the drafting of the 25th Amendment. His book on the amendment had been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. But for most of his career he had not been in academia. He had been one of the first lawyers at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom and built a great practice—one of the rare labor lawyers hired both by corporations and unions. He was making a million dollars a year. And then, at 45, he gave up his partnership to become dean at his beloved Fordham Law, an exceptional financial sacrifice for a man with a wife and young family of six children.

But what I remember most vividly is not his stunning record of achievement, but my first meeting with him. Having experience in government, I anticipated two things. First, that someone with such a record of achievement would be, for want of a better word, conceited, eager to let his subordinates know how impressive he was. Second, that he would be focused on questions of strategy—how to ensure good coverage in the media or how to navigate the complex politics of the City and state.

But, to my astonishment, John was warm and humble. His focus was anything but strategic. At the outset of our meeting, he said he would have one overriding question in mind as he chaired the Commission: "What is the right thing to do?"

Deciding what the right thing to do—and then doing it—has been the guiding principle of John's career.

Of course, "That Further Shore" is not a book of moral philosophy. It is the story of a life, a classic American story.

John is the proud son of Irish immigrants. In "That Further Shore," John describes his experience growing up in the South Bronx in a family of very limited means but with deep faith, great love, and hope in the future. John worked his way through school and his evocation of his jobs along the way—shoveling snow, working in a grocery store, making deliveries for a tailor—is powerful and a wonderful tribute to the value of a work ethic and a beautiful description of a world that is long gone.

It is a moving story of the importance of love and family. John writes beautifully about his parents, his Uncle Pat, and his siblings, as well as his travels to Ireland to discover his roots.

I enjoyed reading about the upbringing of his children, in whom John has great pride, and about his grandchildren. One of the later chapters in the book has an inspiring letter to his grandchildren, reflecting on the lessons he has learned in life. And the book is a valentine to John's beloved wife Emalie and a touching account of the life and family they have built together.

The book offers a unique window into the world of politics and law in the past century and this one. As my reference to his role as chair of the state commission investigating political corruption in the 1980s evidences, John has been a central player in many important stories. The reader of this book will get insights that only John can provide into: the drafting of the 25th Amendment; the rise of Skadden Arps into a position as one of the world's preeminent law firms; his arbitration of the punishment of Golden State Warrior (and future New York Knick) Latrell Sprewell for allegedly choking his coach, a story that dominated the news when it was announced; his dedicated work to combat homelessness in New York City; his fearless leadership of three New York state commissions on government integrity; President Clinton's campaign for peace in Northern Ireland; his leadership roles in the City Bar and the ABA; the important achievements of Fordham Law School's Feerick Center for Social Justice over the past 15 years, including its recent initiatives helping immigrants in Dilley, Texas and its efforts to aid low income veterans; and his work on behalf of the Catholic Church and the deep faith that has shaped his life's work. At the end of each chapter, I found myself thinking: For anyone other than John Feerick, this chapter would have been the highlight of the book. And then I would turn to the next chapter and find another remarkable story.

For those of us who love Fordham Law, John's book is a must-read. In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that I have been working for and with John for much of my adult life. In addition to having worked for John at the Commission on Government Integrity, I was on the Fordham Law faculty for more than a decade when he was dean, and succeeded him as dean in 2002. I look to him as the model of a great academic leader. John is deeply committed to the Jesuit principles of "educating the whole person" and "women and men for others." During his two decade-long deanship and his equally long time as a faculty member he has been guided by that philosophy and shaped a great law school and generations of alumni by: hiring a remarkable faculty of scholars and educators; increasing financial aid to make the school accessible to people of limited means; creating a preeminent clinical program; launching the Stein Institute of Law and Ethics, the Crowley Human Rights Program, and the Public Interest Resources Center; expanding the law school building and laying the plans for the current new building; establishing the Feerick Center, a pioneering program teaching students how to be advocates for social justice; achieving great success in promoting the diversity of the Fordham Law community; and, perhaps most important, modeling for students what it means to be a lawyer concerned with the well-being of each individual he or she meets and committed to the service of others. John has been the key to building a law school that is not simply a great law school, but one that is great in spirit and mission.

So, this is a superb autobiography because it is an inspiring story of family and the importance of roots and a first-hand account of a remarkable series of important moments in history and John's leadership of a great law school. But, above all, it is, to quote the words of a President whom Dean Feerick reveres, a profile in courage.

As I read the book, I was struck again and again by John's courage in so many different settings and different ways throughout his career. He has never been afraid to speak truth to power. For example, when John was a very young lawyer, he was part of the ABA group examining presidential succession. At one session, the revered Harvard Law Professor Paul Freund opined that a commission with representatives from the different branches of government should be created to resolve questions of presidential disability. One can imagine the room of great dignitaries nodding in agreement when Freund, the preeminent constitutional law scholar of his day, offered this solution. But, then, the youngest member of the group spoke up. The 27-year-old John Feerick, a junior associate at a then small law firm, "shyly" pointed out that the proposal violated fundamental principles of separation of powers. Freund listened, and he dropped his proposal.

It is a small story, but John's willingness to challenge a legend reflects who John is. John says and does what he knows is right, regardless of the opposition he will face. With the support of Fordham's extraordinary president, the late Father Joseph O'Hare, he recognized Fordham Law's first gay student rights group in the 1980s, a pioneering decision at a Catholic school. Leading three state commissions investigating corruption, he pursued reform in the face of strong opposition and personal attack. He did not rescind an invitation to speak at Fordham Law's graduation that the school had extended to Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro, the first woman to be nominated for national office and a most distinguished graduate of Fordham Law, even as he was decried from pulpits across the City because of the Congresswoman's pro-choice views. His decision in the Sprewell case was widely decried, but he thought the punishment the NBA had imposed was not justifiable. As an educator, a practicing lawyer, and as a leader of the bar, he has fought in many ways and over many decades for the protection of the most vulnerable members of our society, repeatedly battling the powerful to help homeless people, immigrants, and people without meaningful access to the legal system. Because of who he is, John is loved, but he has never been guided by a desire to be popular. He always asks, "What is the right thing to do?" And then he does it.

We live in a dark time, and we all need heroes. John Feerick is my hero. If you read this book, he will be yours.

William M. Treanor is dean and Paul Regis Dean Professor of Law at Georgetown Law School and former dean of Fordham Law School.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

'We Learn Much From the Court's Mistakes': Law Journal Review of 'The Worst Supreme Court Decisions, Ever!'

6 minute read

'Midnight in Moscow': A Memoir From the Front Lines of Russia's War Against the West

9 minute read

'There Are Heroes in Every Story': Review of 'The Eight: The Lemmon Slave Case and the Fight for Freedom'

9 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Treasury GC Returns to Davis Polk to Co-Chair White-Collar Defense and Investigations Practice

- 2Decision of the Day: JFK to Paris Stowaway's Bail Revocation Explained

- 3Doug Emhoff, Husband of Former VP Harris, Lands at Willkie

- 4LexisNexis Announces Public Availability of Personalized AI Assistant Protégé

- 5Some Thoughts on What It Takes to Connect With Millennial Jurors

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250