The New York City Council's Newest COVID-19 Rent and Judgment Relief Proposal Likely Violates the Takings Clause

In addition to the profound negative economic consequences that the Bill would have, the Bill likely runs afoul of the U.S. Constitution's Takings Clause because it creates government-coerced tenancies without just compensation to property owners.

May 29, 2020 at 11:00 AM

11 minute read

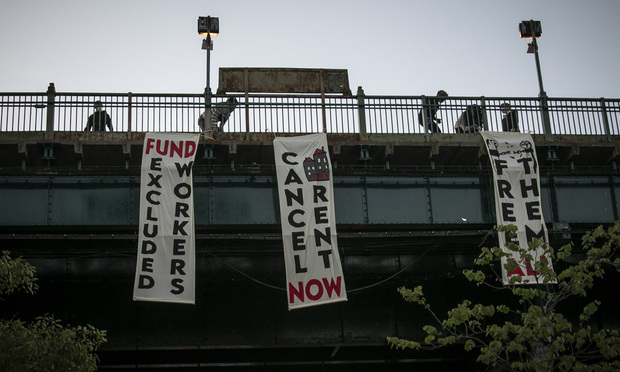

May 21, 2020. People in Corona Plaza, Queens, N.Y unfold banners from a subway platform during a vigil memorializing more than sixty persons who died from COVID-19 and were associated with Make the Road New York. AP Photo: Bebeto Matthews

May 21, 2020. People in Corona Plaza, Queens, N.Y unfold banners from a subway platform during a vigil memorializing more than sixty persons who died from COVID-19 and were associated with Make the Road New York. AP Photo: Bebeto Matthews

On April 22, 2020, the New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson introduced a bill meant to give much needed relief to residential and commercial tenants suffering from the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic (the Bill). The Bill—Int. No. 1912, titled "A Local Law in relation to ceasing the taking and restitution of property and the execution of money judgments by the City sheriff and marshals due to the impacts of COVID-19"—is intended to effectively extend the existing federal and New York state moratoria on evictions by directing New York City marshals and sheriffs not to enforce any possessory or money judgments until as late as April 2021, so long as the judgment debtor can show a court that it has suffered a "substantial loss of income" because of COVID-19. The Bill is part of a larger tenant-focused legislative package, some parts of which the City Council has already recently approved.

In addition to the profound negative economic consequences that the Bill would have—among other significant oversights, the Bill does not consider how property owners would be expected to pay their property taxes, mortgages, staff salaries, maintenance costs, utilities, and other expenses without rent revenue for nearly a full year, nor does it address how the City would make up for the significant shortfall in the City's largest source of tax revenue—the Bill likely runs afoul of the U.S. Constitution's Takings Clause because it creates government-coerced tenancies without just compensation to property owners.

Takings Clause Challenges

The Bill would be ripe for attack either as effecting either a physical taking or a regulatory taking, for which property owners would be entitled to just compensation under the Fifth Amendment, as incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court has articulated two categories of government action that generally qualify as per se takings: (1) government action that causes an owner to suffer a physical invasion of its property; and (2) "regulations that completely deprive an owner of 'all economically beneficial us[e]'" of its property. Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A., 544 U.S. 528, 538 (2005) (emphasis in original). Regulatory action that does not fit into one of those two categories is evaluated by reference to the following criteria: "(1) the economic impact of the regulation on the claimant; (2) the extent to which the regulation has interfered with investment-backed expectations; and (3) the character of the governmental action." Connolly v. Pension Benefit Guar., 475 U.S. 211, 225 (1986); Penn Central Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104, 124 (1978).

The fact-specific question of when regulation rises to the level of a taking places heavy emphasis on the economic effects of government regulations and the extent to which they interfere with reasonable expectations of property owners. If government regulation of real property goes "too far" in burdening property owners' rights to possess, use or dispose of property, then it is considered a regulatory taking. Penn. Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393, 415 (1922); Manocherian v. Lenox Hill Hosp., 643 N.E.2d 479, 482 (N.Y. 1994).

Per Se Takings

Property owners would be on solid ground arguing that the Bill's forced continued tenancies effect a physical invasion of their property.

It is axiomatic that the right to exclude others from one's property is "one of the most essential sticks in the bundle of [property] rights." Kaiser Aetna v. United States, 444 U.S. 164, 176 (1979). The physical occupation or the regulatory action causing the physical invasion need not be permanent to qualify as a taking. First English Evangelical Lutheran Church of Glendale v. Los Angeles, 482 U.S. 304, 318 (1987). Additionally, physical occupation by a third party under the government's authority can constitute a taking. Seawall Assocs. v. City of New York, 542 N.E.2d 1059, 1063 (N.Y. 1989) (citing Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV, 458 U.S. 419, 432-33, n. 9 (1982)).

The Bill hamstrings property rights—specifically the rights to possession and to legally exclude others—to such an unreasonable extent that property owners are essentially compelled by the government to give physical possession of their property for free until April 2021 to a tenant who would otherwise no longer have that right, and against whom the property owner has already obtained a possessory judgment.

In Seawall Assocs. v. City of New York, 542 N.E.2d at 1064, the Court of Appeals held that a New York City law with similar forced control over property owners' possessory interests infringed upon the owners' right to exclude others and effected a physical taking. The City law at issue in Seawall forced Single Room Occupancy (SRO) landlords to refurbish their SRO buildings and keep them fully rented. The court struck down the law as "impos[ing] on the property owners more than their just share of such societal obligations" and effecting a physical taking. Id. at 1062-64. Although the law at issue in Seawall forced property owners "to accept the occupation of their properties by persons not already in residence," whereas the Bill here forces upon property owners continued occupation by their existing defaulting tenants, the "most important" possessory right of property owners to exclude others is no less disturbed by a defaulting tenant's continued possession solely by force of government coercion. Id. at 1063.

The Bill would likely effect a taking, notwithstanding its temporary duration. The Seawall court dismissed the contention that the temporary nature of the statute there at issue removed it from the Takings Clause, stating that the law "results in a deprivation of the owners' quintessential rights to possess and exclude and, therefore, amounts to a physical taking … for whatever time period it is in effect." Id. at n. 5 (citing First English Evangelical Lutheran Church, 482 U.S. at 318).

As the Seawall court noted then, the Supreme Court still "has not passed on the specific issue of whether the loss of possessory interests, including the right to exclude, resulting from tenancies coerced by the government would constitute a per se physical taking." However, just as the Court of Appeals held that the statute in Seawall amounted to a physical taking, "it is difficult to see how" the Bill, which would result in "forced occupancy of one's property could not [amount to a physical taking]." Id. at 1064. "By any ordinary standard, such interference with an owner's rights to possession and exclusion is far more offensive and invasive than the easements … or the installation of the CATV equipment" that the Supreme Court has previously held to constitute physical takings. Id.

With respect to the second category of per se takings, the disastrous economic effect of the Bill cannot be understated. The Bill deprives property owners of "all economically beneficial us[e]" of their property in situations where tenants are not paying rent and owners can neither evict the tenants nor enforce money judgments against them. Property owners who rent their property give up exclusive use of the property to their tenants, but only so long as the tenant remains in possession and pays the agreed-upon rent. If a tenant does not pay, the owner's remedy is either to seek a possessory judgment and/or a money judgment so that the owner can continue to enjoy the economic benefits of property ownership. The Bill neutralizes this remedy. Indeed, even if the owner were to obtain a possessory or money judgment against a tenant, that tenant would be free not to pay any current use and occupancy to the owner knowing that the owner has no legal remedy until April 2021. Meanwhile, owners would be compelled to effectively give their properties away for almost a year without any compensation.

Regulatory Takings

Even if the Bill does not rise to a per se taking, it nevertheless may satisfy the Supreme Court's factors for finding a regulatory taking.

It is clear that the first factor, the "economic impact of the regulation," on property owners is satisfied by an owner's inability to collect rent until April 2021 and the likelihood of owners losing their properties without income from the rent roll, either in foreclosure or for non-payment of property taxes.

With respect to the second factor, "the extent to which the regulation has interfered with investment-backed expectations," a property's rent roll is the central piece of data that informs investment expectations in the real estate market. Property owners, investors, and lenders rely upon a property's rent roll to make sound investment, management, and financial decisions about real property. To effectively statutorily suspend rent collection and prohibit owners from regaining possession of their properties for almost a full year—which could tank property values and cause owners to lose their properties—is economically devastating and represents unprecedented interference with investment-backed expectations in real property.

The third factor, the "character of the governmental action," is generally understood as asking whether the government is physically invading a property or whether it has instituted a "public program adjusting the benefits and burdens of economic life to promote the common good." Penn Central, 438 U.S. at 124. Here, as discussed, the forced continued tenancies that the Bill would create would amount to physical invasion of property. That alone satisfies the third factor for finding a regulatory taking. Moreover, the Bill does not reflect a "public program adjusting the benefits and burdens of economic life to promote the common good." The "[e]lementary and strong constitutional principles that protect private property rights and govern takings of property for public use without just compensation" specifically "evolved to bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole." Manocherian, 643 N.E.2d at 481. The economic burdens of property owners and tenants following the COVID-19 pandemic should be "borne by the public as a whole," not solely by property owners. Yet the Bill promotes the interests of a discrete class of businesses and individuals at the expense of property owners by disproportionately saddling only owners with the economic burdens of their tenants while exacerbating those owners' own post-pandemic existential financial hardships.

Finally, laws that make it "commercially impracticable" to exercise property rights have been found to constitute regulatory takings. Penn. Coal v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393, 414-15 (1922). The Bill creates a favored, protected class of tenants at the expense of making property ownership commercially impracticable for owners equally affected by the pandemic.

Just Compensation

The Bill awards property owners no just compensation for the takings it effects. On the contrary, even though it technically does not absolve tenants of their rent obligations, the Bill would likely cause many owners to lose their properties for failure to pay property taxes or in foreclosures well before they are permitted to enforce judgments and collect rent. As a practical matter, even once the Bill permits the execution of judgments after April 2021, there is no guaranty that money judgments will ever be collectible because the judgment debtors may file for bankruptcy protection prior to execution of the judgments. As general creditors, judgment creditors may never be able to collect on their judgments. In addition to interfering with collecting on money judgments, filing for bankruptcy would trigger an automatic stay of all proceedings outside of bankruptcy court that would further delay execution of possessory judgments. It would take property owners months and additional legal fees and expenses—all of which they would incur while not receiving any rent revenue or any government compensation—to lift the automatic bankruptcy stay and regain possession of their property.

Conclusion

The next few months will be a critical time for our fragile economy during which the policies enacted by legislators could either make or break our recovery. In their search for novel solutions to an unprecedented crisis, legislators must be mindful of the constitutional limitations on their authority to interfere with private property rights and contractual rights as they consider policies to ease the burdens of the pandemic. Indeed, though not addressed in this Article, it is possible that the Bill violates not only the Takings Clause, but the Contracts Clause as well. Legislators must also account for the grim economic realities suffered not only by tenants, but by property owners and judgment creditors. Any relief measures for tenants and debtors must also include commensurate relief for property owners and creditors to avoid causing more harm and financial instability.

Eliad S. Shapiro is an associate at Smith & Shapiro in Manhattan, where he practices commercial litigation and real estate litigation. He can be reached at [email protected].

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Tortious Interference With a Contract; Retaliatory Eviction Defense; Illegal Lockout: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Court of Appeals Provides Comfort to Land Use Litigants Through the Relation Back Doctrine

8 minute read

Piercing the Corporate Veil; City’s Authority To Order Restorations; Standing: This Week in Scott Mollen’s Realty Law Digest

Trending Stories

- 1New York-Based Skadden Team Joins White & Case Group in Mexico City for Citigroup Demerger

- 2No Two Wildfires Alike: Lawyers Take Different Legal Strategies in California

- 3Poop-Themed Dog Toy OK as Parody, but Still Tarnished Jack Daniel’s Brand, Court Says

- 4Meet the New President of NY's Association of Trial Court Jurists

- 5Lawyers' Phones Are Ringing: What Should Employers Do If ICE Raids Their Business?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250