Court Examines Powers of Law Enforcement When Acting Outside Jurisdiction in Traffic Stop

In their New York Court of Appeals Roundup, Neuner and Russell review a recent decision in which the Court of Appeals examined the powers of law enforcement officers acting outside the scope of their jurisdiction to stop a vehicle for traffic violations and effectively conduct an "arrest."

July 21, 2020 at 01:15 PM

7 minute read

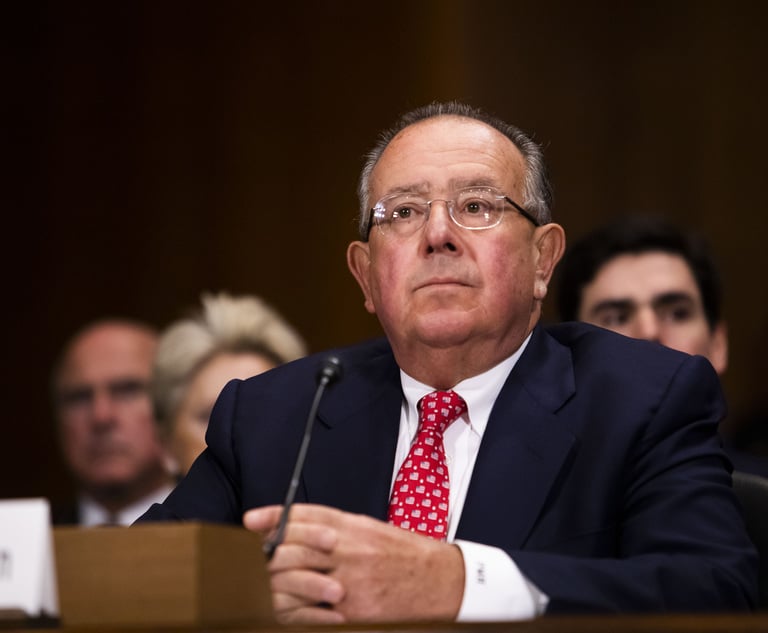

Lynn K. Neuner and William T. Russell Jr.

Lynn K. Neuner and William T. Russell Jr.

In a recent decision, the Court of Appeals examined the powers of law enforcement officers acting outside the scope of their jurisdiction to stop a vehicle for traffic violations and effectively conduct an "arrest." The majority in People v. Page denied a motion to suppress evidence seized during a traffic stop by a law enforcement official on the grounds that he was making a citizen's arrest in a decision that focused on the specific language of the governing Criminal Procedure Law provisions. The dissent, on the other hand, placed greater emphasis on the policy rationale behind those provisions in arguing that the seized evidence should be suppressed. This divided decision concerning appropriate limitations on police power and people's ability to make citizen arrests is of particular interest given the recent efforts to reexamine fundamental aspects of law enforcement and self-policing in our society.

In June 2017, an on-duty federal marine interdiction agent with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) was driving an unmarked SUV on Interstate 190 in Erie County. The SUV was equipped with an emergency radio and a limited number of emergency lights in its front grille and windshield, but lacked the full suite of lights and sirens usually found on police vehicles. The agent saw a car occupied by the defendant and two other individuals driving erratically and barely avoiding multiple collisions. The agent followed the car and unsuccessfully attempted to report the incident to the State Police on his emergency radio. He then called 911 on his personal phone and was transferred to the Buffalo Police Department. As his call was being transferred, the agent followed the defendant's car as it exited the highway and continued to drive erratically through the local streets. The agent testified that he was concerned for public safety and activated the emergency lights on his SUV in order to stop the car. The car pulled over, and the agent reported the license plate and location to the Buffalo police and waited approximately five minutes for a police officer to arrive. A single police officer arrived and the agent approached the vehicle with him for what the majority and the Fourth Department described as "safety reasons." The agent saw the police officer speaking with the occupants, but the agent did not speak to any of them and left the scene when additional Buffalo police officers arrived and told him that he was no longer needed.

After the agent left, the Buffalo police officers searched the car and found a gun. All three of the occupants were arrested, and the defendant was charged with criminal possession of a weapon in the second degree. The Supreme Court, Erie County granted a pretrial motion to suppress the gun as the result of an unlawful seizure. The Appellate Division, Fourth Department affirmed in a unanimous decision, and the Court of Appeals granted the people's application for leave to appeal.

Both the Supreme Court and the Fourth Department relied on the Court of Appeals' prior decision in People v. Williams, 4 NY3d 535 (2005), in suppressing the gun recovered from the stopped vehicle. That case involved two Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority officers who, pursuant to CPL 2.10[17], are expressly included in the ambit of "persons designated as peace officers." As peace officers, their police powers are subject to specific limitations set forth in CPL 140.25, including with respect to the power to make an arrest outside the geographic area of their employment. The officers saw the defendant driving without a seatbelt outside the officers' geographical jurisdiction, stopped the defendant and recovered a bag of crack cocaine from him. The defendant was charged with criminal possession of a controlled substance but successfully moved to dismiss the charges. The Appellate Division affirmed the dismissal. In affirming the Appellate Division, the Court of Appeals rejected the People's argument that, even though the officers were outside their geographic area of employment, their warrantless arrest was the equivalent of a citizen's arrest pursuant to CPL 140.30, which permits any person to effect an arrest under certain circumstances. The Court of Appeals ruled that allowing the officers to effect a citizen's arrest pursuant to CPL 140.30 that they were prohibited from effecting as peace officers would render meaningless the legislature's restrictions on the police powers of peace officers. The Court of Appeals noted that it was not holding that an individual employed as a peace officer could never make a citizen's arrest. Rather, it is only "a peace officer who acts under color of law and with all the accouterments of official authority" who cannot effect a citizen's arrest.

In the Page case, the majority opinion written by Judge Paul G. Feinman and joined by Chief Judge DiFiore and Judges Stein, Garcia and Wilson focused on the question of whether the marine interdiction agent was a peace officer. Unlike the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority officers at issue in Williams, federal agents are not included in CPL 2.10's exclusive list of "persons designated as peace officers." CPL 2.15 does, however, provide limited peace officer powers to certain federal law enforcement officers including "United States Customs and Border Protection Officers and United States Customs and Border Protection Border Patrol agents." The majority found that the express language of the statute does not refer broadly to all CBP agents but is limited to CBP "Officers" and "Border Patrol agents" and, accordingly, does not include air and marine agents like the agent in this case. Because the agent is not considered a peace officer or a federal law enforcement agent with peace officer powers pursuant to the CPL, he could not have improperly relied on the citizen's arrest provisions of CPL 140.30 to circumvent the limitations placed on police powers of peace officers. Accordingly, Williams does not apply, and the gun seized as a result of the agent's actions in stopping defendant's car is not subject to suppression. The majority emphasized that it was solely deciding the question of whether the courts below properly applied Williams. The majority noted that other potential claims, such as those based on state or federal constitutional rights, were not raised by the defendant.

Judge Eugene M. Fahey, joined by Judge Rivera, issued a dissenting opinion arguing that allowing a law enforcement official who is neither a police officer nor peace officer to effectively impersonate one in order to effect an arrest would undermine the rationale of the court's decision in Williams. According to the dissent, because the agent was acting under color of law and with the outward characteristics of official authority, he was in fact acting as a peace officer. Expanding the reach of the citizen's arrest provisions of the CPL in this manner raises the prospect of increased vigilantism which, as the dissent notes, is of particular concern given incidents in recent years where what the dissent describes as "neighborhood watch group or homeowners' association members, and similar vigilantes have engaged in aggressive conduct, often with tragic consequences." Accordingly, the dissent views this case as squarely within the holding of Williams and would affirm the Appellate Division's and Supreme Court's suppression of the seized evidence.

In reaching opposite conclusions, the majority focused on the specific definition of peace officer to find the marine interdiction agent's actions outside the scope of Williams whereas the dissenting judges emphasized the policy rationale of Williams and examined what they viewed as the practical effect of eroding limits on the police powers of peace officers and expanding citizen's arrest powers.

Lynn K. Neuner and William T. Russell Jr. are partners at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

Private Equity Giant KKR Refiles SDNY Countersuit in DOJ Premerger Filing Row

3 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Rules Brutality Claims Against Hudson Valley Police Officer to Proceed to Trial

Skadden and Steptoe, Defending Amex GBT, Blasts Biden DOJ's Antitrust Lawsuit Over Merger Proposal

4 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250