US Supreme Court Ruling Opens Door for Registration of 'Generic.com' Marks

In 2011 and 2012, Booking.com, a digital travel company that allows consumers to make hotel and other reservations online, filed applications to register trademarks with various visual features, all for travel-related services, and all including the term "Booking.com," writes Rob Maier in his Patent and Trademark Law column.

July 21, 2020 at 12:30 PM

9 minute read

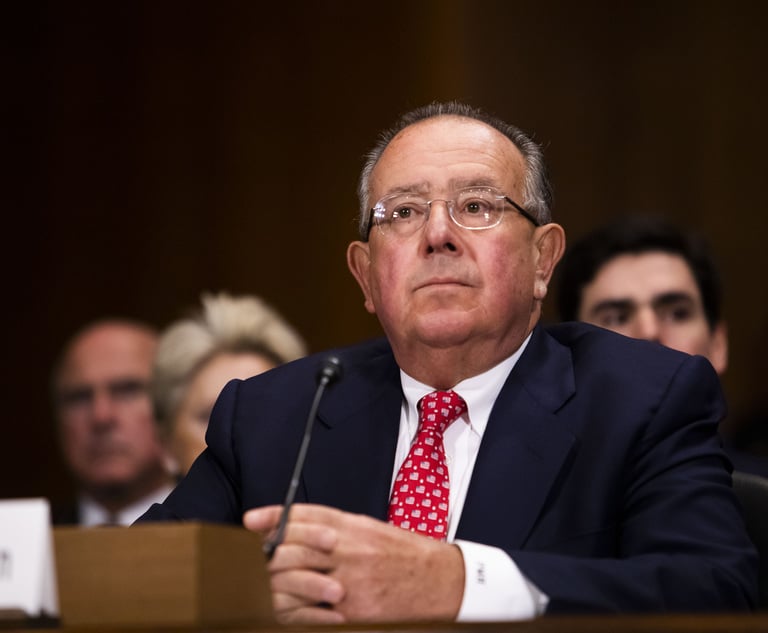

Robert L. Maier

Robert L. Maier

In 2011 and 2012, Booking.com, a digital travel company that allows consumers to make hotel and other reservations online, filed applications to register trademarks with various visual features, all for travel-related services, and all including the term "Booking.com." See United States Patent & Trademark Office v. Booking.com B. V., No. 19-46, 2020 WL 3518365, at *3 (U.S. June 30, 2020). The trademark examiner at the USPTO, followed by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, rejected the applications on the ground that "Booking.com" was a generic term for the services, and was therefore ineligible for registration. According to the board, since "Booking" means making travel reservations and ".com" indicates a commercial website, consumers would necessarily understand "Booking.com" to refer to an online reservation tool for travel, tours, and lodgings. The board further indicated that even if "Booking.com" were descriptive, the term lacked any secondary meaning that would make it registrable.

Booking.com sought review of the board's decision in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, allowing it to introduce new evidence concerning consumer perception. See Booking.com B.V. v. Matal, 278 F. Supp. 3d 891, 915 (E.D. Va. 2017). The district court, relying in large part on this new evidence, found that "Booking.com" is not generic. Specifically, the court determined that survey evidence showing "that the consuming public understands BOOKING.COM to be a specific brand, not a generic name for online booking services" indicated that the term was capable of designating source and thus potentially registrable. The Fourth Circuit, on appeal, affirmed the lower court decision and, in June 2020, the Supreme Court affirmed. The court found that whether a "generic.com" term is generic, for the purpose of federal trademark registration, depends on consumer perception of the term. Booking.com, Because "Booking.com" is not perceived by consumers as the name of a class of online hotel-reservation services, but is instead recognized as a term capable of distinguishing between members of the class, the term is not generic, and therefore eligible for federal trademark protection.

Background

The Lanham Act provides the framework within which the USPTO may determine eligibility of a trademark for federal registration: registrable trademarks are marks "by which the goods of the applicant may be distinguished from the goods of others." The more distinctive a trademark, the more likely the trademark is to be considered eligible for placement on the principal register, barring other factors that may come into play. Distinctiveness is oftentimes evaluated on a scale with generic terms being the least distinctive, followed by descriptive terms, suggestive terms, arbitrary terms, and finally fanciful terms, which are typically considered the most distinctive. Generic terms are typically ineligible for trademark protection, as they do not fulfill one of the primary objectives of trademark law, namely to enable consumers to distinguish one producer's goods from those of another based on the term alone. Id. Similarly, descriptive terms are usually ineligible for registration on the principal register absent a showing of "acquired distinctiveness" or "secondary meaning," meaning that they hold a certain significance "in the minds of the public" as indicating a particular applicant's goods or services.

The U.S. District Court's Decision

After Booking.com's applications were rejected by the USPTO, the case went to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. Booking.com B.V. v. Matal, 278 F. Supp. 3d 891 (E.D. Va. 2017). The district court was confronted with Booking.com's presentation of novel evidence of consumer perception of "Booking.com," leading the court to conclude that the relevant public "primarily understands that BOOKING.COM does not refer to a genus, rather it is descriptive of services involving 'booking' available at that domain name." The district court concluded that "Booking.com" is both descriptive and has acquired secondary meaning with regard to hotel-reservation services, and therefore, the mark is distinctive enough to be eligible for registration.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed that decision, rejecting the USPTO's argument that a generic term combined with ".com" is necessarily generic, and following, the USPTO sought review by the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari.

The Supreme Court in Booking.com

The Supreme Court was confronted with a single question: whether any "generic.com" term is generic for the purpose of federal trademark registration. After hearing oral arguments (by phone, due to COVID-19) and reviewing several amicus briefs filed by companies who employ their own "generic.com" brand names, such as Salesforce.com, Cars.com, and Dictionary.com, the Supreme Court affirmed the Fourth Circuit decision, countering several arguments made by the USPTO, and ultimately rejecting the USPTO's stance that the trademark "Booking.com" is per se generic because, as a rule, combining a generic term with ".com" yields a generic composite.

First, the court determined that the question of whether a term is generic turns on whether the entire term signifies to consumers the class of goods or services. In fact, the court pointed out that the USPTO itself has not consistently applied its own purported rule, pointing to registrations granted for ART.COM on the principal register and DATING.COM on the supplemental register.

Second, the Court countered the USPTO's reliance on an 1888 case, Goodyear's India Rubber Glove Manufacturing v. Goodyear Rubber, 128 U.S. 598, 602 (1888), which held that the mark "Goodyear Rubber Company" was not eligible for protection. Because "Goodyear Rubber" was considered generic, as it referred to an established class of goods, the addition of the word "Company" to the mark had no effect on the registrability of the mark; adding "Company" simply indicated that the owner or user of the mark "Goodyear Rubber Company" "formed an association or partnership to deal in such goods." The USPTO relied on the Goodyear case, arguing that the addition of ".com" was akin to the addition of "company"—and adding ".com" to a generic term added no meaning to the mark, such that the ".com" would not aid consumers in distinguishing different providers' services.

The Supreme Court rejected this argument, concluding that a "generic.com" term may in fact add additional source-identifying meaning to a mark, namely "an association with a particular website." Id. And because domain names are unique and only one entity may hold a particular domain name at a time, consumers may understand a "generic.com" term to reference the specific corresponding website or website owner. Id. The Supreme Court additionally pointed out the USPTO's misinterpretation of Goodyear as dismissing the importance of how "consumers would understand" the term. Id. In fact, Goodyear stood for the notion that whether a compound term is generic depends on how consumers perceive the term—and whether there is any additional meaning in the minds of consumers based on the addition of other terms.

Third, the majority opinion went on to ease the USPTO's fears, echoed in Justice Stephen Breyer's dissent, that allowing marks like "Booking.com" to proceed to registration would dissuade competitors from using similar language to "booking." Id. at *7. The majority noted that this concern, which accompanies any descriptive mark, is already tempered by a few considerations, namely the fact that consumers are not likely to be confused by marks containing generic or highly descriptive terms based on the presence of those terms, and the doctrine of classic fair use, which protects anyone who uses a descriptive term from liability if the mark is used "fairly and in good faith" and "otherwise than as a mark."

Who Will Pay?

While the trademark issue has now been resolved, a question remains: who will pay for Booking.com's victory? The Fourth Circuit had ordered Booking.com to pay the USPTO $76,000 in attorneys' fees, despite having won the case, following its prior precedent in Nantkwest, Inc. v. Matal, 860 F.3d 1352, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2017). Booking.com B.V. v. United States Patent & Trademark Office, 915 F.3d 171, 188 (4th Cir.). Although Booking.com had appealed the Fourth Circuit's award of attorney's fees, the issue had been put on hold until the issue of eligibility for trademark protection was settled. On July 2, 2020, the justices granted the petition for review, vacated the ruling, and sent the case back to the Fourth Circuit for a determination on the fee question, in view of the 2019 decision in Peter v. Nantkwest, where the Supreme Court ruled that the USPTO could not recover attorney fees, as the requirement in Section 145 of the Patent Act that the applicant be responsible for "all expenses of the proceedings" did not include attorney's fees, and this provision likewise does not overcome the American Rule's presumption against fee shifting. 35 U.S.C. Section 145; Peter v. Nantkwest, 140 S. Ct. 365, 370, 373, 205 L. Ed. 2d 304 (2019). The Fourth Circuit's determination on attorney's fees will likely have an important impact on trademark owners' willingness to seek de novo review of USPTO decisions, given the significant costs.

Looking Ahead

Ultimately, the Supreme Court's holding on the registrability of generic marks with an added ".com" designation underscores the importance of consumer perception in registrability issues. With this in mind, companies would be wise to monitor, collect, and maintain evidence of consumer perception throughout the life of a trademark, especially those looking to claim rights in generic.com terms. Consumer perception forms one of the bedrocks of registrability for marks that may toe the line of distinctiveness, and concrete evidence can mean the difference between "booking" a spot on the federal register and rejection.

Rob Maier is an intellectual property partner in the New York office of Baker Botts LLP, and the head of its intellectual property group in New York. Suzi Hengl, special counsel at Baker Botts, and Meghna Prasad, a Baker Botts law clerk, assisted in the preparation of this article.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Decision of the Day: JFK to Paris Stowaway's Bail Revocation Explained

Decision of the Day: Judge Dismisses Defamation Suit by New York Philharmonic Oboist Accused of Sexual Misconduct

Private Equity Giant KKR Refiles SDNY Countersuit in DOJ Premerger Filing Row

3 minute read

Decision of the Day: Judge Rules Brutality Claims Against Hudson Valley Police Officer to Proceed to Trial

Law Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

- 1Class Action Litigator Tapped to Lead Shook, Hardy & Bacon's Houston Office

- 2Arizona Supreme Court Presses Pause on KPMG's Bid to Deliver Legal Services

- 3Bill Would Consolidate Antitrust Enforcement Under DOJ

- 4Cornell Tech Expands Law, Technology and Entrepreneurship Masters of Law Program to Part Time Format

- 5Divided Eighth Circuit Sides With GE's Timely Removal of Indemnification Action to Federal Court

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250