Who Is Judge James Selna and Why Is His Trial Record Under Review?

A rule change in the Central District of California ended an unusual practice of other judges deciding recusal motions targeting their colleagues. Now an unusual request in Michael Avenatti's cross-country criminal cases is putting a California trial record before a judge in the Southern District of New York.

January 10, 2022 at 07:11 PM

11 minute read

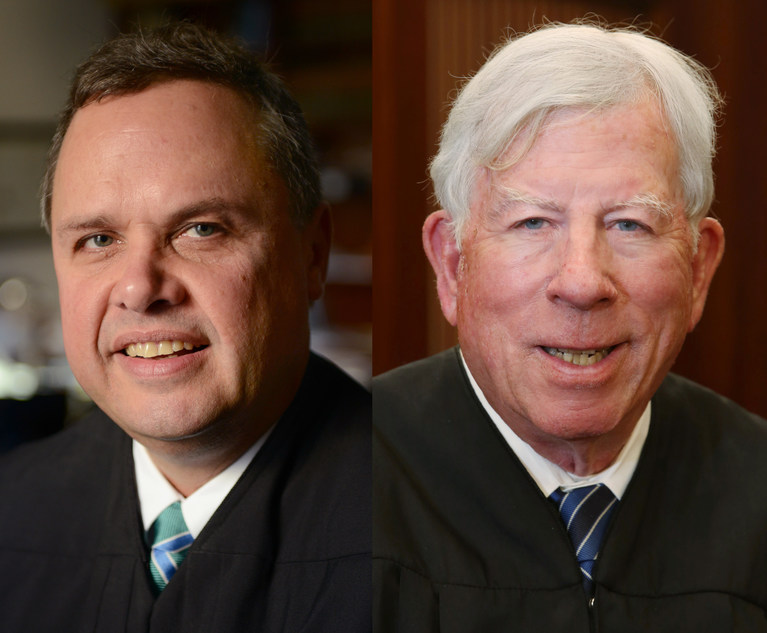

U.S. District Judge Paul G. Gardephe of the Southern District of New York, left, and U.S. District Judge James V. Selna of the Central District of California, right. Photos: Rick Kopstein/Jamie Rector/ALM

U.S. District Judge Paul G. Gardephe of the Southern District of New York, left, and U.S. District Judge James V. Selna of the Central District of California, right. Photos: Rick Kopstein/Jamie Rector/ALM

Before he declared a mistrial in Michael Avenatti's wire fraud trial, the federal judge presiding over the nearly three-year-old case was at the forefront of another high-profile issue unique to the Central District of California: the review of his own colleagues' work.

For decades, the Los Angeles-based district where Judge James Selna presides required recusal motions against trial judges to be decided by a bench colleague, which put jurists in the unusual situation of reviewing each other in sometimes controversial cases.

The judges rarely ordered their colleagues to recuse—court watchers can recall only one occasion—but Selna's reputation as a straight shooter made at least one of the jurists whose motion went before him nervous.

"The highest compliment I can give to my good friend Jim Selna is I was worried," said retired U.S. District Judge Andrew J. Guilford, now a mediator with Judicate West in Santa Ana, California.

Selna didn't grant the recusal motion against Guilford over an alleged ethics violation, "but he would have if I had screwed up, and that is Selna," Guilford said.

Last year, the Central District's rules committee changed the process so that recusal motions stay with the case judge, unless that judge believes unusual circumstances warrant outside review.

Chief District Judge Philip S. Gutierrez of the Central District of California.

Chief District Judge Philip S. Gutierrez of the Central District of California. "The Central District was really an outlier in how it handled recusals," Chief Judge Philip Gutierrez said in an interview. "What the rule change does is make the district in compliance with the statute related to recusals."

Now the multi-case prosecution of Avenatti has put Selna's work before another trial judge in the Southern District of New York, with U.S. District Judge Paul Gardephe requesting full transcripts from key days in Avenatti's wire fraud trial and Selna's post-mistrial hearings.

It's far from a recusal motion, and a law professor who knows Gardephe well cautioned against inferring the transcript requests as some kind of bid to scrutinize another trial judge. But a trial court record going before another trial court still is unusual, and Avenatti's initial success in trying to pit his dual prosecutions against each other means Gardephe will read Selna's work before the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals scrutinizes it in an appeal that's set for oral argument in March.

"The fact that he asked to see some materials is just, I think, part and parcel of the care in which he approaches any decision that he makes," said Gardephe's friend Daniel Richman, a professor at Columbia Law School.

It also highlights the complexity of the U.S. Department of Justice's cross-country pursuit of Avenatti, whose current legal arguments involve the idea that federal prosecutors in California and New York are essentially the same team, so evidence used in one case should lawfully be disclosed to him in another if it could be exculpatory.

Unusual Post-Trial Request

Gardephe requested the transcripts as part of his review of Avenatti's request that the judge issue an indicative ruling telling the Second Circuit Court of Appeals he'd vacate Avenatti's Nike extortion convictions and grant a new trial if he had jurisdiction.

The request is based on the newly discovered financial information on Avenatti's seized law firm servers that prompted Selna to declare the mistrial in California. It puts before Gardephe an unusual post-conviction evidentiary issue under Brady v. Maryland that asks him to consider the relationship between prosecutors who work in separate districts but were after the same defendant.

When does evidence in one case become relevant to another?

A Dec. 2 letter from Avenatti's current lawyer in the Nike case, Benjamin Silverman, says the California case is clearly related to the Nike case, as California prosecutors were in New York "working on witness prep during the trial in this case and seated at times in the courtroom."

That means information prosecutors used in the California case to try to show how Avenatti misappropriated client money should have been provided to Avenatti in the Nike case as possible exculpatory evidence, Silverman argues, because it contradicts the theory that Avenatti was desperate for money when he was negotiating with Nike's lawyers.

Selna said prosecutors in his case committed no misconduct by failing to locate financial information about Avenatti's firm stored through the Tabs3 billing software program, rather, the judge said it was a case of not fully appreciating what was there. That lack of misconduct solidified his decision not to dismiss the case on double jeopardy grounds, which Avenatti is appealing to the Ninth Circuit.

Daniel Richman, a professor at Columbia Law School.

Daniel Richman, a professor at Columbia Law School. But while the Ninth will consider whether Selna's decision was legally sound, Gardephe is essentially tasked with deciding whether he would have made a similar mistrial decision had he seen the same information during the Nike trial in January and February 2020.

Does he believe the law firm financial information could be exculpatory?

Richman, who worked alongside Gardephe when they were assistant U.S. attorneys in the 1980s, said his friend's lack of jurisdiction makes such a careful approach inevitable.

"This is a smart, thoughtful, incredibly painstaking person," Richman said. "He's incredibly thoughtful, deliberative and prepares more than anyone I've ever seen."

Similar But Divergent Backgrounds

Selna, 76, and Gardephe, 65, both were nominated by President George W. Bush, with Selna confirmed in 2003 and Gardephe 2008.

Selna first served five years as a California Superior Court judge in Orange County; he took federal senior status in March 2020 but has yet to noticeably reduce his caseload.

Both he and Gardephe have law degrees from top schools—Selna from Stanford in 1970 and Gardephe Columbia in 1982—but their litigation experience differs: Gardephe was a federal prosecutor for nine years, a general counsel at Time Inc. for seven and a litigation partner at Patterson Belknap for five before he joined the bench. His work with the Department of Justice continued after he left the U.S. Attorney's Office: He led DOJ reviews of the FBI's handling of two espionage cases from 1995 to 1997 and from 2001 to 2003.

Both judges are soft-spoken: Richman described Gardephe as "definitely more on the understated side," while Selna's friend Derek Hunt, an Orange County Superior Court judge, said Selna is well known for being at times barely audible.

"We go out to dinner with him and I'm constantly leaning across the table trying to hear what he wants to say," Hunt told Law.com. "Don't go to a noisy restaurant with Judge Selna."

Selna, who was editor of the Stanford Daily student newspaper as an undergraduate, spent his 27-year litigation career entirely at O'Melveny & Myers, where he worked major cases such as the defense of Exxon in the Valdez oil spill, and antitrust cases involving client IBM in the 1970s. He's referenced those experiences several times in the Avenatti case, including telling prosecutors he knew that computer data "however voluminous," must be able to be copied and delivered.

"I know a little bit about computers," he said.

Selna reiterated that at a later hearing, telling Avenatti: "Look, I've spent many years litigating. I've been working with litigation databases until the '70s."

A friend and former bench colleague said Selna is "well equipped to understand and rule on pretty technically complicated issues associated with discovery."

"His comment and his reaction is not a surprise to me," said Phillip R. Kaplan of Umberg Zipser in Irvine, California. "In the IBM cases, they developed and Jim was involved in methods of both recovering documents, producing documents and tracking them and searching them. That whole industry did not exist before those cases. The consultants that worked with the firm established businesses based on that."

Selna's key discovery decisions in the Avenatti case date back to shortly after Avenatti's arrest, when he denied Avenatti's requests for unfettered access to Avenatti's law firm servers. He essentially reversed course after the newly discovered financial data prompted the mistrial: On Sept. 15, he ordered the U.S. Attorney's Office to provide Avenatti with complete copies of the forensic image of each server.

Unusual Cases, Unusual Decisions

Avenatti is citing the servers as an example of what he describes as ongoing discovery violations in the Southern District wire fraud and identity-theft case involving the now ex-client who propelled him to fame, Stormy Daniels. His public defenders have referenced the mistrial in California in their filings to U.S. District Judge Jesse M. Furman, who so far has not sought the additional California trial records that Gardephe has in the Nike case as the issues before them differ.

"I would be averse to thinking that he would assert jurisdiction over a matter that he might not have jurisdiction over without taking care to examine the precedent and the basis," Richman said of Gardephe.

Gardephe's high-profile cases have included unusual decisions. In 2014, he overturned a jury's conviction for kidnapping conspiracy against a New York police officer accused of plotting cannibalism.

Selna's major cases have included a Mexican Mafia leader's criminal trial and multi-district litigation over Toyota's unintended acceleration malfunctions. But one of his most high-profile rulings in Orange County occurred not in a case assigned to him but in a recusal motion that went to him before the Central District changed the procedure for deciding recusals.

In what many say is the only judge recusal granted in recent Central District history, Selna in 2019 recused Judge David O. Carter in a civil rights lawsuit against three Orange County cities that don't have homeless shelters.

The cities hired Jones Day lawyers who referenced comments Carter made that they said indicated he was dead set on forcing the cities to build shelters and that they couldn't be treated fairly, and Selna agreed a reasonable observer could conclude Carter is "not unbiased." The decision sparked news coverage and major discussion in Orange County's judicial circles, but the judges remain on good terms: Carter said he joined Selna for coffee in his chambers afterward to make sure of it.

"That's a tough decision, a really tough decision. But he wouldn't flinch at that," said Hunt, who met Selna when they were superior court judges. "I bet there wasn't even the slightest change in their relationship because Jim is so sweet. He just does what he has to do. And Dave would understand that. It wouldn't be an issue."

Prior to Avenatti's request to Gardephe, Selna's decisions had already affected the Nike case: Selna revoked Avenatti's bail six days before the Nike extortion trial was to start in Gardephe's Manhattan courtroom, leading Gardephe to delay the trial by one week.

But the current request from Avenatti for an indicative ruling from Gardephe to the 2nd Circuit is less about Selna and more about the U.S. attorney's offices in New York and California, whether they're considered one unit and whether evidentiary issues in California also are issues in New York.

Retired U.S. District Judge Andrew Guilford

Retired U.S. District Judge Andrew Guilford Gardephe has made no indication when he'll issue a ruling, and he's got plenty of time before the 2nd Circuit considers the case: Avenatti's opening brief isn't due until Feb. 11.

Selna's friends said Selna's trial records are undoubtedly complete.

"He's extremely thoughtful and cautious," Hunt said.

Guilford, whose chambers were next to Selna's for 14 years, said he was "happy for the country" when Selna was assigned Avenatti's case.

Guilford said, "I think his courageous rulings in that case reflect his dedication."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Honored by NYSBA, 2nd Circuit Chief Judge Livingston's Remarks Stress Judicial Safety

3 minute read

Justice in the 21st Century, New Visions, New Realities—A New Dawn of Justice

4 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250