The Hornblower Decision and Fugitive Slaves in NJ

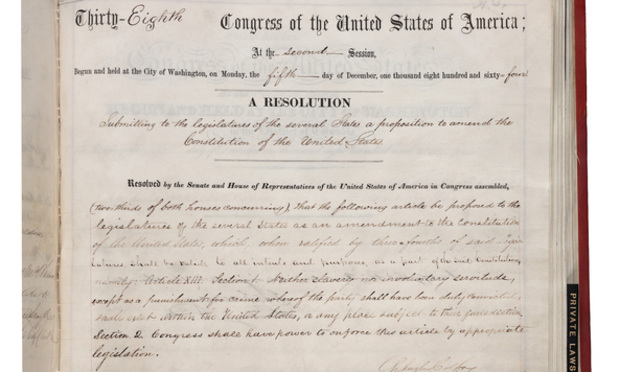

Slavery existed in New Jersey from early colonial times until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery in 1865.

February 12, 2018 at 08:00 AM

9 minute read

Joseph C. Hornblower was the Chief Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court from 1832 to 1846. He died on June 11, 1864. His New York Times obituary described him as a generally well-regarded lawyer and jurist whose decisions were “marked by learning, legal acumen and high moral principle.” His claim to historical importance arises out of his 1836 opinion in State v. Sheriff of Burlington County identifying constitutional deficiencies in the Fugitive Slave Act (FSA) of 1793.

This federal statute allowed escaped slaves to be reclaimed and also permitted misidentified free African-Americans to be kidnapped and placed into slavery. Unfortunately the full opinion was not officially published. There are contemporaneous newspaper accounts summarizing the ruling. In 1851 the opinion's most important part was published in a pamphlet. It is reprinted in 1 Fugitive Slaves and American Courts: The Pamphlet Literature 97-104 (Paul Finkelman ed. 1988).

Overview of the Historical Context

Slavery existed in New Jersey from early colonial times until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery in 1865. In fact, New Jersey was the last Northern state to outlaw slavery. G. Wollentz, “New Jersey Slavery and the Law,” 50 Rutgers L.Rev. 2227, 2228 (1998). Legislation passed in 1804 had only provided for the “gradual abolition of slavery.” A statute enacted in 1846 stated that “slavery in this state be and it is hereby abolished” but left all the former slaves as “apprentices” or “servants” of their owners for the rest of their lives. That only changed with the Thirteenth Amendment.

The attitude toward slavery in New Jersey has been attributed to the supposed fact that the southern one-third of the state is below the Mason-Dixon Line, the traditional dividing line between free and slave states. However, the Mason-Dixon Line does not actually cross New Jersey. Furthermore, until 1865, the northern counties had more slaves than the southern counties. Most of the southern counties were part of West Jersey, heavily influenced by the Quaker settlers who dominated the area's population and opposed slavery. The early Quaker abolitionist John Woolman was from Burlington County.

Nonetheless, the southern counties were the frequent hunting ground of slave-catchers tracking down escapees from the slave-holding states who came across the Delaware River into Salem County. The constitutional basis for pursuing the escapees was Article IV, Section 2:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

In 1793 Congress implemented the Fugitive Slave Clause with the FSA. This statute allowed an owner or an owner's agent to seize someone allegedly a fugitive slave and have them brought before a federal judge or a local magistrate. With undefined “proof to the satisfaction” of the judge or magistrate that the person seized was really a fugitive and was owned by the claimant, the judge or magistrate could issue a certificate authorizing the claimant to remove the fugitive to the state from which he or she had allegedly fled. Even if the captured person contested the claim, no hearing was required. There were no procedural safeguards. The FSA authorized the imposition of criminal penalties on any person who obstructed the capture of a fugitive, or who rescued, aided or concealed the fugitive. Early case law provides an unsettling attitude toward the subject matter of these laws.

In Gibbons v. Morse, 7 N.J.L. 253 (E & A 1821), New Jersey's highest court declared: “In New Jersey, all black men are presumed to be slaves until the contrary appears.” A 1798 New Jersey statute supplemented the federal FSA but was replaced in 1826 with another statute requiring a warrant from a local judge before a fugitive slave could be seized and removed. Procedural safeguards were still largely absent.

The Helmsley Case

In 1835 a Maryland slave-owner's representatives came to New Jersey seeking a warrant for a man known as Alexander Helmsley, claiming Helmsley was actually Nathan Mead who escaped from Maryland in 1820. He was brought before a Burlington County judge. Over several days witnesses from Maryland testified they recognized Helmsley as Nathan.

The Burlington County judge was expected to rule that Helmsley was the claimant's escaped slave and order his return to Maryland. However, one of Helmsley's lawyers traveled overnight to Newark to obtain a writ of habeas corpus from Chief Justice Hornblower. The writ was served on the sheriff just as the judge was rendering his decision to send Helmsley back to Maryland.

The writ brought the case to the New Jersey Supreme Court. A three-justice panel in Trenton ruled on March 3, 1836, that Helmsley was to be discharged from custody of the sheriff. Following his release, Helmsley relocated to Canada.

Hornblower's Analysis

In his opinion for the court, Chief Justice Hornblower noted that both Congress and the New Jersey General Assembly had enacted legislation concerning the Fugitive Slave Clause but with different modes of proceeding. Acknowledging the Constitution and federal law pursuant to the Constitution as “the supreme law of the land,” he questioned Congress' constitutional authority to determine the manner for resolving a claim in which a person in a free state is to be arrested and transferred to another simply because they are alleged to be slaves. He pointed to the text and structure of the Fugitive Slave Clause in Article IV rather than Article I. Nothing in it gave Congress power to pass such a law. Furthermore, the Clause only required returning those who actually owed service and not those who were merely claimed to have that obligation. While his comments regarding lack of congressional power to enact the legislation presaged a declaration of unconstitutionality, the Chief Justice said it was not necessary to rule on that since the case before him had been based on the New Jersey statute enacted in 1826 and not the 1793 FSA. He highlighted features of the state law. It allowed seizure and transport of a person out of the state with only a summary hearing before a single judge without a jury or right of appeal. Hornblower posed the rhetorical question: “Can such a law be constitutional?” The opinion has several instances of impassioned writing regarding a person “dragged in chains” and being “falsely accused of escaping.” Responding to the contention that a seized suspected fugitive would eventually have a hearing, the Chief Justice wrote:

What, first transport a man out of the state, on the charge of his being a slave, and try the truth of the allegation afterwards separate him from the place, it may be, of his nativity — the abode of his relatives, his friends, and his witnesses — transport him in chains to Missouri or Arkansas, with the cold comfort that if a freeman he may there assert and establish his freedom! No, if a person comes into this state, and here claims the servitude of a human being, whether white or black, here he must prove his case, and here prove it according to law….

For Hornblower, this meant a jury trial. The Chief Justice also rejected the presumption of slave status based on skin color and “the danger of oppression and injustice by an unfounded or mistaken claim.” He pointed out that by statute as of the next Fourth of July no person of color in New Jersey under the age of 32 would be a slave because pursuant to the statute providing for “gradual abolition” of slavery “[a]ll that have been born since the 4th July, 1804, are freemen.”

Aftermath

In apparent response to the 1836 Helmsley decision, in 1837 the legislature revised the procedures regarding fugitive slaves to provide for a jury trial.

In 1844, New Jersey adopted a new constitution. Article I stated that “All men are by nature free and independent, and have certain natural and unalienable rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and of pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness.” In State v. Post, 20 N.J.L. 368 (Sup. Ct. 1845), the court considered the contention that adoption of the new constitution abolished slavery. A majority of the Supreme Court ruled that it did not. Chief Justice Hornblower dissented. He retired the next year.

The progressive view set forth in the Chief Justice's opinion in State v. Sheriff of Burlington County was effectively rejected by the United States Supreme Court in the 1842 decision of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. 539 (1842), but without any reference to the unpublished New Jersey decision. In his opinion for the court, Justice Joseph Story upheld the constitutionality of the FSA of 1793. This statute was later replaced by the more punitive Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In correspondence dated Sept. 15, 1851, with Salmon P. Chase, then a practicing attorney and United States Senator but later the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, the retired Joseph Hornblower commented on this new Fugitive Slave Act: “The law of 1850, even if Congress has a right to legislate on the recapture of runaway slaves, is a disgrace to our Country, an affront to humanity, an insult to the great principles of the common law, and calculated to provoke disunion and rebellion.” This was a prescient comment. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, often referred to as the Man-Stealing Act, is considered one of the precipitating factors for the Civil War.

Jackson is a partner at McElroy, Deutsch, Mulvaney & Carpenter in Morristown, and a fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

NJDOL's Aggressive Use of Stop Work Orders Is Dramatically Altering the Compliance Landscape for Employers

8 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Prepare Your Entries! The California Legal Awards Have a New, February Deadline

- 2DOJ Files Antitrust Suit to Block Amex GBT's Acquisition of Competitor

- 3K&L Gates Sheds Space, but Will Stay in Flagship Pittsburgh Office After Lease Renewal

- 4US Soccer Monopoly Trial Set to Kick Off in Brooklyn Federal Court

- 5NY AG James Targets Crypto Fraud Which Allegedly Ensnared Victims With Fake Jobs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250