In Racist Juror Case, More Was Needed From SCOTUS Majority

We agree with Justice Thomas' assessment—the majority “says little about how a court of appeals could ever rule in Tharpe's favor on the merits of the prejudice question.”

April 16, 2018 at 11:00 AM

4 minute read

Once again, the Supreme Court has turned back for further review and a possible new trial a capital murder conviction and death sentence because of a juror's racist comments. Tharpe v. Sellers, decided Jan. 8. Tharpe had been convicted of a particularly brutal murder. He ambushed his wife who had left him and forced her into his truck. He then shot her sister, dumped her into a ditch and murdered her, before driving off to kidnap and rape his wife. After unsuccessful appeals to state and federal courts, he again sought habeas corpus relief on the ground that a white juror was biased against him because he is black. The 11th Circuit, federal district and state courts all had concluded that he failed to demonstrate that the juror's “behavior had substantial and injurious effect or influence in determining the jury's verdict.” This conclusion, the five-justice per curiam majority agreed, generally would be binding “in the absence of clear and convincing evidence to the contrary.” The majority found such evidence in an affidavit by a single white juror, interrogated by defense counsel seven years after Tharpe's conviction. As summarized by the majority, the affiant stated: “In his view there are two types of black people,: 1: Black folks and 2. N****r;” that Tharpe, “who wasn't in the 'good' black' folks category in my book, should get the electric chair for what he did”; that some of the jurors voted for death because they felt Tharpe should be an example to other blacks who kill blacks, but that wasn't his reason. The majority concluded that this “remarkable affidavit – which he never retracted” presented a strong factual basis for the argument that Tharpe's race affected the juror's vote for a death verdict, and that at the very least jurists of reason could debate whether Tharpe had shown by clear and convicting evidence that the state court's factual determination was wrong. The court had stayed Tharpe's execution just moments before he was to be lethally injected, granted his petition for certiorari, and without further briefing or argument summarily vacated the 11th Circuit judgment and remanded for further consideration of entitlement to habeas corpus relief.

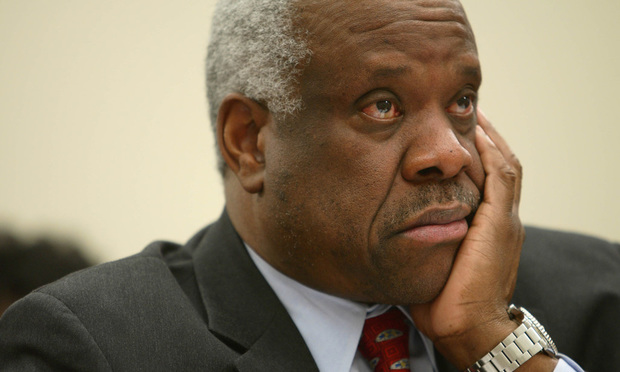

Even putting aside the court's summary disposition, which is reserved for the most unusual cases, the court's per curium opinion is troubling. The majority's summary of the pivotal affidavit was accurate enough as far as it went, but omitted among other things that, two days later, the state obtained another affidavit from the juror where, among other things, he stated that he “did not vote to impose the death penalty because [Tharpe] was a black,” but instead “because the evidence presented at trial justified it and because Tharpe showed no remorse.” Further, that when he signed the first affidavit, he had been drinking for several hours. Ten jurors, including two African-Americans, testified and the 11th swore in an affidavit that race was not a factor in their deliberations. As dissenting Justice Thomas complained, the majority's conclusion plows through three levels of deference; to trial courts' findings on questions of juror bias; to state courts' factual findings in habeas proceedings; and to discretionary decisions of federal district courts under Rule 60(b).

This whole business may well be an exercise in futility. As the majority concedes, “It may be that, at the end of the day” Tharpe will not succeed. We agree with Justice Thomas' assessment—the majority “says little about how a court of appeals could ever rule in Tharpe's favor on the merits of the prejudice question.” Indeed, on remand what more can the 11th Circuit do but rethink its earlier conclusions? It cannot even remand for further findings with respect to the juror's contradictory affidavits because he is dead. At most, then, the court's decision merely delays Tharpe's inevitable execution.

Finally, we footnote again our hostility to the death penalty, which we long have felt should be abolished. It serves no purpose other than revenge, as Justice Thomas impliedly conceded when he concluded passionately that the majority's “unusual disposition of [this] case callously delays justice for the black woman who was brutally murdered by Tharpe 27 years ago.” Like so many others, this case has dragged on for over 27 years since Tharpe first was convicted, and because of the result here will go on for many more, consuming countless hours of judicial and lawyer time better spent, and costing perhaps millions more dollars for the endless proceedings which follow. Tharpe's death, when the state finally kills him, will not deter others, as numerous studies have demonstrated. Better to lock him up in the most legally permissible inhospitable surroundings and throw away the key.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

As Trafficking, Hate Crimes Rise in NJ, State's Federal Delegation Must Weigh in On New UN Proposal

4 minute read

Appellate Court's Decision on Public Employee Pension Eligibility Helps the Judiciary

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Former U.S. Dept. of Education Attorney Suspended for Failure to Complete CLE Credits

- 2ArentFox Schiff Adds Global Complex Litigation Partner in Los Angeles

- 3Bittensor Hackers, Accused of Stealing Over $28 Million, Face Federal Lawsuit

- 4In Novel Oil and Gas Feud, 5th Circuit Gives Choice of Arbitration Venue

- 5Jury Seated in Glynn County Trial of Ex-Prosecutor Accused of Shielding Ahmaud Arbery's Killers

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250