Permit Local Taxing of Out-of-State Retailers

We think 'Quill Corp v. North Dakota' was wrong and hope the Supreme Court will so hold.

April 30, 2018 at 11:00 AM

7 minute read

Laurent Delhourme

Laurent Delhourme For generations states have been barred by the dormant commerce clause from requiring retailers to collect sales taxes unless they have a “physical presence” in the taxing state, thanks to two Supreme Court decisions. National Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Dept of Revenue, 386 U.S. 753 (1967) so held based on both the due process and dormant commerce clauses. Quill Corp v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992) followed. The court unanimously agreed that due process was no obstacle to imposing a sales tax collection obligation on retailers, but a five-person plurality reaffirmed Bellas' interstate commerce burden holding, agreeing that compelling foreign retailers to collect sales taxes placed an unconstitutional burden on interstate commerce. Now, South Dakota has directly confronted that rule and asked the Supreme Court to overrule Quill. South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. (No. 17-494).

The moral and practical consequences of Bellas and Quill are obvious. Local and state governments, particularly those which have no income tax and rely almost solely on sales and use tax revenues, are extraordinarily harmed. As South Dakota has documented in its presentations to the Supreme Court, in 2012 state and local governments were owed an estimated $23 billion in taxes uncollected because of Quill, and $33.9 billion losses in 2018, and $211 billion from 2018-2022, are projected. To make up the shortfall, most states raise sales-tax rates, driving more consumers to avoid them by purchasing online. The states can ill afford losing these monies, which Justice Kennedy, concurring in Direct Mktg. Ass'n v. Brohl, 135 S. Ct. 1124 (2015), noted could be used for “education systems, healthcare services, and infrastructure.” Secondly, Quill unconscionably subsidizes internet retailers to the detriment of local mom-and-pop stores, who have enough difficulty as it is competing with them, but must also collect sales taxes from which the former are exempted.

We think Quill was wrong and hope the Supreme Court will so hold. The Supreme Court in Complete Auto Transit v. Brady, 430 U.S. 274 (1977), prescribed a different test to determine when non-resident businesses conducting interstate commerce in a state may be constitutionally asked to contribute their “just share” in collecting that state's taxes. State statutes imposing tax obligations on out-of-state retailers are permitted if (1) they are “applied to an activity with a substantial nexus with the taxing State;” and are (2) “fairly apportioned,” (3) not “discriminatory” and (4) “fairly related to the services provided by the State.” In short, “substantial nexus” between the taxing state and the taxed person or activity, not “physical presence,” is the operative issue. The Quill plurality and three others upheld Bellas on stare decisis grounds, but the five person plurality went further, ratifying the Bellas “bright-line” “physical presence” test because it furthers “the ends of the dormant Commerce Clause” since it is easy to apply by demarcating “a discrete realm of commercial activity that is free from interstate taxation…[it] creates a safe harbor for vendors 'whose only connection with customers in the [taxing] state is by common carrier or the U.S. mail,'” quoting Bellas Hess. The plurality admitted its rationale had not been adopted in other cases which approached the constitutionality of tax issues on a case-by-case factual basis, but “the continuing value of a bright line rule in this area and the doctrine and principles of stare decisis indicate that the Bellas Hess rule remains good law,” especially so because “Congress remains free to disagree with our conclusions [and decide]… whether, when and to what extent the States may burden interstate mail-order concerns with a duty to collect taxes.” This approach, the plurality felt, was not “inconsistent” with Complete Auto. We think it was. As to “the supposed convenience of having a bright -line rule,” dissenting Justice White objected, “I am less impressed by the convenience of such adherence than the unfairness it produces.”

Justice White's dissent persuasively argued that “What we disavowed in Complete Auto was not just the formal distinction between 'direct and indirect' taxes on interstate commerce,' but also the whole notion underlying the Bellas Hess physical presence rule—that interstate commerce is immune from state taxation.” He disagreed with the plurality's rationale that “nexus” for due process considerations was different from the “nexus” required to burden interstate commerce. “Nexus,” he felt, “is really a due process fairness inquiry” for both purposes, particularly with respect to parts two and three of the Complete Auto test, which “required fair apportionment and nondiscrimination in order that interstate commerce not be unduly burdened.” The physical presence test “perhaps long ago was a sufficient part of a trade to condition imposition of a tax on such a presence…but in today's economy [it] frequently has very little to do with a transaction a State might seek to tax. An out-of-state direct marketer derives numerous commercial benefits from the State in which it does business,” such as local banking institutions to support credit transactions, courts to ensure collection of the purchase price, waste disposal of garbage generated by mail order solicitations—all sufficient to establish the necessary nexus.

At least three present Supreme Court justices have signified their distaste for Quill and indicate they are prepared to overrule it. Justice Kennedy, who concurred in Quill solely on stare decisis grounds, later commented in Direct Mktg Ass'n v. Brohl (2015) that Quill was “questionable even when decided.” He invited “[t]he legal system…to find an appropriate case for this Court to reexamine” it. South Dakota has accepted this invitation by enacting the statute now before the court. It mimics the North Dakota law rejected by Quill by requiring out-of-state retailers to collect its sales tax on goods sold to in-state residents. The Legislature made no bones about its deliberate intent to “overrule” Quill. Justice Thomas now advocates abandoning it, and Justice Gorsuch, then on the court of appeals circuit that decided Direct Mktg., opined that Quill has its own rule—“an expiration date” to “wash away with the tides of time.” It is, he wrote, a “precedential island, surrounded by a sea of contrary law.”

Stare decisis is no hurdle. The Supreme Court has been quite willing to overrule its precedent when there is a constitutional or statutory issue. Quill itself overruled Bellas Hess' due process holding without worrying about the doctrine which, hornbook law shows, looks to whether history has engendered reliance interests, the precedent has been undermined by changed circumstances, has been consistently criticized, and has been unworkable or outdated by experience. South Dakota meets all these tests. The concerns expressed by Quill and Bellas Hess about the logistical problems national mail-order retailers might face in collecting sales taxes for multiple jurisdictions are imaginary horribles. As Justice White 36 years ago and Justice Kennedy more recently have noted, technological advances in computing make it easy for retailers to collect different state sales taxes. The large-scale internet retailers which cannot pass the “physical presence” test and must collect sales taxes do so with ease. Systemic, an original defendant, agreed to comply with South Dakota's new law and was up and running in less than two days. Quill argued that the physical presence requirement had become “part of the basic framework of a sizeable [mail order] industry which relied on the bright line exemption from state taxation.” The changed circumstances noted by Justices Kennedy and White compel overruling Quill, and the drum-beat criticism of the Quill result by commentators, lower courts, the states themselves, numerous amici and three current Supreme Court justices, all dictate that the time for Quill to go has come.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

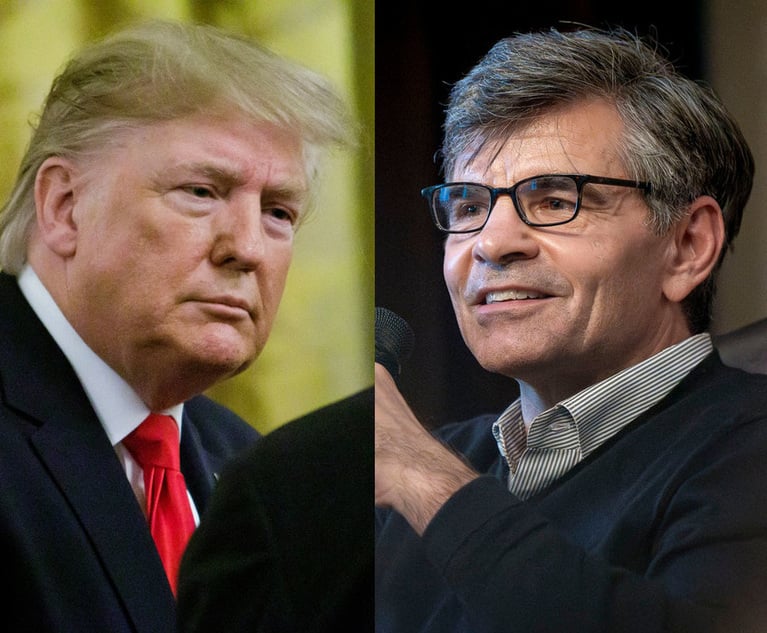

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

As Trafficking, Hate Crimes Rise in NJ, State's Federal Delegation Must Weigh in On New UN Proposal

4 minute read

Appellate Court's Decision on Public Employee Pension Eligibility Helps the Judiciary

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1In Novel Oil and Gas Feud, 5th Circuit Gives Choice of Arbitration Venue

- 2Jury Seated in Glynn County Trial of Ex-Prosecutor Accused of Shielding Ahmaud Arbery's Killers

- 3Ex-Archegos CFO Gets 8-Year Prison Sentence for Fraud Scheme

- 4Judges Split Over Whether Indigent Prisoners Bringing Suit Must Each Pay Filing Fee

- 5Law Firms Report Wide Growth, Successful Billing Rate Increases and Less Merger Interest

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250