Can a 'Unitary' Contract Compel Arbitration? Appellate Division's Answer Warrants Publication

The holding of Victory Entertainment Inc. v. Schibell is sufficiently noteworthy for publication. We welcome the “back to basics” approach.

July 23, 2018 at 11:00 AM

3 minute read

shutterstock.com

shutterstock.com

Our courts regularly struggle with whether a person has standing to compel arbitration of claims arising from one of several documents, only one of which contained an arbitration clause. When the moving party had not signed the arbitration document, the response often was to deny a motion to compel arbitration. In Angrisani v. Financial Technological Ventures L.P., 402 N.J. Super. 138 (App. Div. 2008), for example, an employment agreement contained an arbitration clause. When the employer sought to compel arbitration of a claim under a contemporaneously executed stock purchase agreement, which did not itself require arbitration, the trial court found that the documents and claims were sufficiently interrelated to require arbitration. The Appellate Division reversed. The employment agreement explicitly limited arbitration to disputes between the employer and employee, not the parties to the stock purchase agreement, and the appeals court believed the contracts and claims were not sufficiently interrelated to justify arbitration. Angrisani was relied on, in part, in Hirsch v. Amper Financial Services LLC, 215 N.J. 174 (2013), which held that equitable estoppel was not a sufficient basis under New Jersey law for requiring arbitration on the so-called entwinement theory of contract and party inter-relatedness.

The Appellate Division recently held, in an unpublished opinion, that documents that were part of a unitary or integrated transaction may give rise to a duty to arbitrate claims against a signatory to one of the documents even though that person had not signed the document that contained an arbitration clause. Victory Entertainment Inc. v. Schibell, A-3388-16T, 2018 N.J. Super. Unpub. LEXIS 1467 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Jun. 21, 2018). The holding of the decision is sufficiently noteworthy for publication, but coming from a two-judge panel, it is not eligible.

The facts of the underlying transactions were developed in six days of hearings. As part of a reallocation of the parties' interests in several adult entertainment business entities and an effort to mask one party's interest in the businesses, all four executed stock certificates, three executed a sales agreement, and two executed a deadlock agreement. Only the latter contained an arbitration clause.

When a signatory to the deadlock agreement was removed from his ownership position, he sued. A signatory to the sales agreement, but not the deadlock agreement, moved to compel arbitration. The trial court held that he had standing to invoke the arbitration clause in a document he did not sign because the documents, read together, were a “unitary contract.” They were part of the same commercial transaction, had internal cross references to each other, were executed contemporaneously, and pertained to control and management of the same business.

Victory Entertainment is one of the few arbitration cases to view multiple documents as an integrated or unitary contract. It came to that conclusion under generally applicable principles of contract and agency law. It discussed non-arbitration commercial cases—apparently not cited before in this context—invoking the unitary contract principle. The cases go back as far as 1947, and they are insulated from the policy considerations attendant to more recent consumer cases involving adhesion contracts. We welcome the “back to basics” approach.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

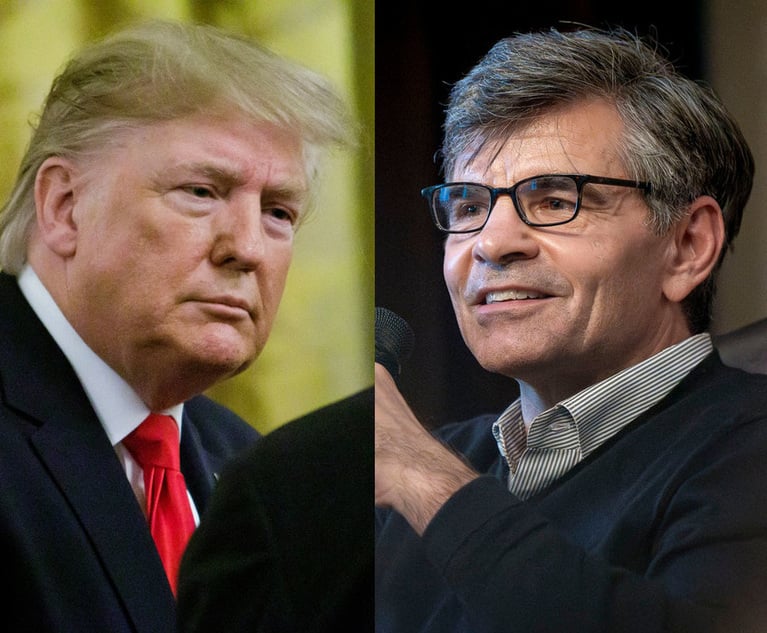

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

As Trafficking, Hate Crimes Rise in NJ, State's Federal Delegation Must Weigh in On New UN Proposal

4 minute read

Appellate Court's Decision on Public Employee Pension Eligibility Helps the Judiciary

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Fresh lawsuit hits Oregon city at the heart of Supreme Court ruling on homeless encampments

- 2Ex-Kline & Specter Associate Drops Lawsuit Against the Firm

- 3Am Law 100 Lateral Partner Hiring Rose in 2024: Report

- 4The Importance of Federal Rule of Evidence 502 and Its Impact on Privilege

- 5What’s at Stake in Supreme Court Case Over Religious Charter School?

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250