Insider Trading Statute Needed

Congress should enact a specific insider trading statute without further delay. There is simply no downside to it.

August 20, 2018 at 10:00 AM

4 minute read

Credit: TZIDO SUN/Shutterstock.com

Credit: TZIDO SUN/Shutterstock.com

Congressman Chris Collins was arrested on Aug. 8, 2018, on charges that he engaged in insider trading. The 58-page indictment returned by the grand jury in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York charged in unusual detail that an Australian biotechnology company, of which Collins was a board member, had learned that a drug which it was hoping to produce for the treatment of multiple sclerosis had totally failed its trial testing. Upon learning that, Collins allegedly contacted his son as well as others to tell them that the drug in question had failed its trial. That information resulted in the immediate sale of the stock of the company, prior to the public announcement of the drug's trial failure. That is alleged to have resulted in the tipees avoiding more than $768,000 in losses. Rep. Collins has been quoted as denying guilt and expressing the expectation that he will be acquitted. We know nothing about the facts of this case other than those set forth in the indictment, and would not and do not intend to express any view of guilt or innocence.

However, this case, as so many others of recent vintage, is based on a number of legal theories including securities fraud in violation of Title 15, United States Code, Sections 78(j)(b) and 78(ff). Also alleged in the indictment is that the securities fraud violated Title 17, Code of Federal Regulations, Sections 240.10b-5. We note that nowhere in the indictment is there a reference to a specific federal statue defining insider trading. That is because no such statute exists, although many legal commentators and scholars have long expressed the view that prosecutions for insider trading would be facilitated if there were a specific statute setting forth the elements of the offense. It has been said that those who prosecute these cases prefer the fact that there is no statutory definition of insider trading, inasmuch as the absence of a statutory definition allows in some respects greater liberality in a trial of such cases than would otherwise be the case if there were a specific statutory definition of the offense.

The most recent case decided by the United States Supreme Court on insider trading was Salman v. United States, 580 U.S. ___ (2016). In that case, Justice Alito, writing for the unanimous court, dispelled the notion held by some federal courts that liability for insider trading could only be properly established if the tipper not only breached the fiduciary duty to maintain confidential information and not disclose it, but also, as a result of disclosing it, received a financial benefit. In some cases, the inability to show that the tipper received such a benefit resulted in an acquittal or a reversal of a conviction on appeal.

The Supreme Court resolved any ambiguity on that issue by holding that insider trading can be properly established even where the tipper does not receive money or property as a result of the breach of a fiduciary duty. Rather, it was held that a personal benefit resulted even from simply making a gift of confidential information to a friend or relative. In other words, a benefit in the form of cash was not required in order for a conviction to obtain.

While Salman resolved this issue, it did not deal with other potential ambiguities that almost inevitably result from the lack of a statutory definition of insider trading. Thus, we take this opportunity to repeat what we have espoused in the past, i.e., that Congress should enact a specific insider trading statute without further delay. There is simply no downside to it, and such statute would obviate a number of proof problems that have plagued the courts in these kinds of cases.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

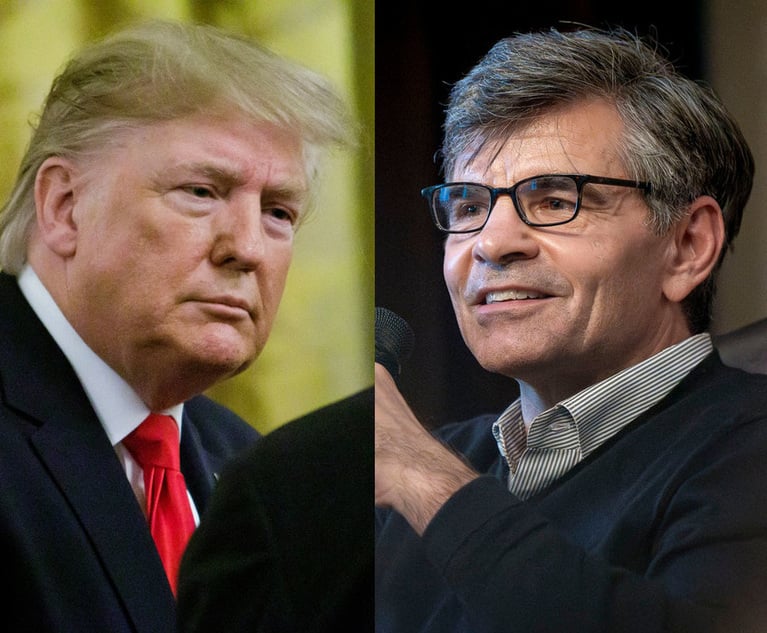

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

As Trafficking, Hate Crimes Rise in NJ, State's Federal Delegation Must Weigh in On New UN Proposal

4 minute read

Appellate Court's Decision on Public Employee Pension Eligibility Helps the Judiciary

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Troutman Pepper, Claiming Ex-Associate's Firing Was Performance Related, Seeks Summary Judgment in Discrimination Suit

- 2Law Firm Fails to Get Punitive Damages From Ex-Client

- 3Over 700 Residents Near 2023 Derailment Sue Norfolk for More Damages

- 4Decision of the Day: Judge Sanctions Attorney for 'Frivolously' Claiming All Nine Personal Injury Categories in Motor Vehicle Case

- 5Second Judge Blocks Trump Federal Funding Freeze

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250