Constitution Requires That Whitaker Be Replaced

The Constitution, it seems to us, provides the answer. The continued service of Whitaker will create issues with regard to the legitimacy and validity of any actions he takes. The position should be filled by the deputy attorney general or other available Senate-confirmed officer.

November 23, 2018 at 10:00 AM

3 minute read

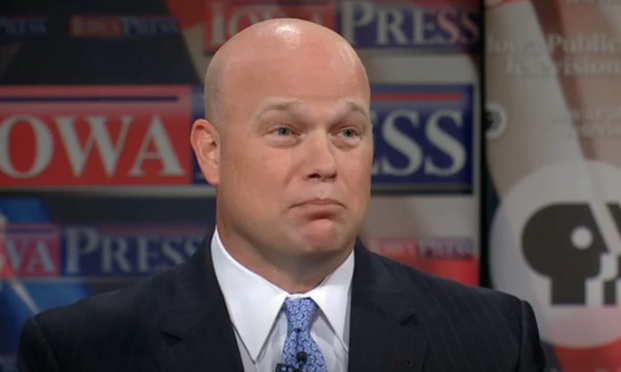

Matthew Whitaker

Matthew Whitaker

The president's day-after-elections discharge of Attorney General Jeff Sessions and replacement with a lawyer who has not been vetted by the Senate has generated a tsunami of commentary and challenges. The appointment of Matthew Whitaker bypassed Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who has overseen Robert Mueller's investigations. Controversy ensued because a statute, 28 U.S.C. 508, specifically designates the deputy as “first assistant” who in the event of vacancy in the office of Attorney General “may exercise all the duties of that office.”

The legality of Mr. Trump's decision has been endorsed by the opinion of the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel. The OLC in a comprehensive memo argues that the president has a choice: follow either the 1977 DOJ succession law §508, or use the 1998 Vacancies Reform Act, 5 U.S.C. 3345. In the event a presidential appointee confirmed by the Senate ”dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office“ the VRA allows the president three choices: fill the vacancy temporarily with the “first assistant,” another Senate confirmed officer, or an employee at the level GS 15 or higher. Whitaker is in the third category. He is now the superior of Senate-confirmed officers, and everyone else in the Department of Justice, including the FBI.

The fundamental choice to be made is whether §508 controls or the VRA offers the president the option to ignore the 1977 DOJ succession law and appoint temporarily an employee (here Sessions' chief of staff) to perform all of the duties of the Office of the Attorney General. To make that decision, several principles are available: the more specific law (508) overrides the more general—the VRA; the VRA does not come into play because Sessions did not “resign” but was constructively discharged after months of public presidential insults and protests; the Constitution mandates the powers of the office of Attorney General be filled—except perhaps in special circumstances such as emergency—by someone appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. We think the Constitution provides the touchstone for that choice.

Article II describes the head of a department as a “principal Officer”…

“[The President] shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors (and)… all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.”

The Constitution, it seems to us, provides the answer. Whitaker is serving as a “principal Officer” but he has neither been nominated by the president nor confirmed by the Senate. The vacancy was created by the president, not by resignation, death, or unavailability of the attorney general. There is no emergency or special circumstance that justifies putting a mere employee such as Whitaker in a position superior to the Senate-confirmed and available officers—the deputy attorney general and the solicitor general. The Constitution has made that choice for principal officers. The continued service of Whitaker will create issues with regard to the legitimacy and validity of any actions he takes. The position should be filled by the deputy attorney general or other available Senate-confirmed officer.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

As Trafficking, Hate Crimes Rise in NJ, State's Federal Delegation Must Weigh in On New UN Proposal

4 minute read

Appellate Court's Decision on Public Employee Pension Eligibility Helps the Judiciary

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Munger, Gibson Dunn Billed $63 Million to Snap in 2024

- 2January Petitions Press High Court on Guns, Birth Certificate Sex Classifications

- 3'A Waste of Your Time': Practice Tips From Judges in the Oakland Federal Courthouse

- 4Judge Extends Tom Girardi's Time in Prison Medical Facility to Feb. 20

- 5Supreme Court Denies Trump's Request to Pause Pending Environmental Cases

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250