U.S. Litigators, Beware the GDPR Issue in Discovery

At a minimum, the lesson to be learned is to raise the issue early in litigation.

November 23, 2018 at 10:00 AM

4 minute read

In federal court, with jurisdiction over the foreign entity, discovery of foreign companies in U.S. litigation may be obtained through federal rules of civil procedure. Societe Nationale Industrielle Aerospatiale v. U.S. Dist. Court for S. Dist. of Iowa, 482 U.S. 522 (1987). However, a foreign company may be placed into conflict where it either complies with U.S. discovery demands and risks criminal liability or other sanctions for violation of its own data privacy laws, or complies with its home law and risk sanctions in the U.S. litigation. In Aerospatiale, the Supreme Court expressly recognized a need for “special vigilance to protect foreign litigants from the danger that unnecessary, or unduly burdensome, discovery may place them in a disadvantageous position,” and that courts recognize “the demands of comity in suits involving foreign states, either as parties or as sovereigns with a coordinate interest in the litigation.”

The European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enforced on May 25, 2018, imposes a set of rules and restrictions on how personal data is handled and transferred. Notably, compliance by American companies with the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield does not ensure full compliance with GDPR, inasmuch as that Privacy Shield was meant to provide a provisional remedy. Companies must still comply with GDPR to the extent the jurisdictional parameters are met.

In perhaps the first case to address the impact of GDPR on American discovery demands since GDPR's enforcement date, an unreported decision shows continued primacy of the obligations of parties to follow discovery demands in U.S. litigation. In Corel Software, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., No. 215CV00528JNPPMW, 2018 WL 4855268 (D. Utah Oct. 5, 2018), the court rejected Microsoft's request for a protective order “barring further retention and production of its telemetry data” in a patent infringement case. Among other arguments, Microsoft argued that retention of such data created “tension with Microsoft's obligations under the European General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679.” The court agreed with plaintiff that Microsoft had failed to show undue burden or expense in compliance. A review of the motion papers on the docket reveals that Microsoft simply raised the issue as noted above, indicated a willingness to submit further briefing, but the court decided the matter on the papers before it.

The enforcement of the GDPR does not change the parameters of the analysis by a court in the United States, whether federal or state. As recognized in Aerospatiale, the Restatement of Foreign Relations Law of the United States notes five factors relevant to the comity analysis: “(1) the importance to the … litigation of the documents or other information requested; (2) the degree of specificity of the request; (3) whether the information originated in the United States; (4) the availability of alternative means of securing the information; and (5) the extent to which noncompliance with the request would undermine important interests of the United States, or compliance with the request would undermine important interests of the state where the information is located.” These would apply whether or not the foreign law is simply a “blocking statute” precluding general transmittal of documents, or a privacy law addressing personal data, or both. American courts require proofs of plausible risk of enforcement of criminal and civil penalties by foreign authorities, not just possibilities; see. e.g., Knight Capital Partners Corp. v. Henkel Ag & Co., KGaA, 290 F. Supp. 3d 681, 691 (E.D. Mich. 2017).

Reasonable minds may differ as to whether the current approach under Aerospatiale and the Restatement, as developed in the case law, is sufficient to handle the issue post-GDPR. Perhaps had Microsoft had the opportunity to further brief and develop its point, it might have tipped the scale. Perhaps not. On the minimal information before it, the Corel court probably got it right.

At a minimum, the lesson to be learned is to raise the issue early. At least in federal court, the forms preceding the initial conference provide an opportunity to raise issues relating to discovery regarding data privacy. We do not believe the local or federal rules, or even the New Jersey state court rules, need to be changed to address this. The rules of discovery currently in place regarding electronic discovery and overly burdensome discovery should be sufficient. However, practitioners need to anticipate and raise such issues early, together with reserving the right to assert the application of foreign law, and be aware of the preventative measures that can be taken by clients in terms of where data is stored and processed, to minimize the potential for significant exposure to their clients.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

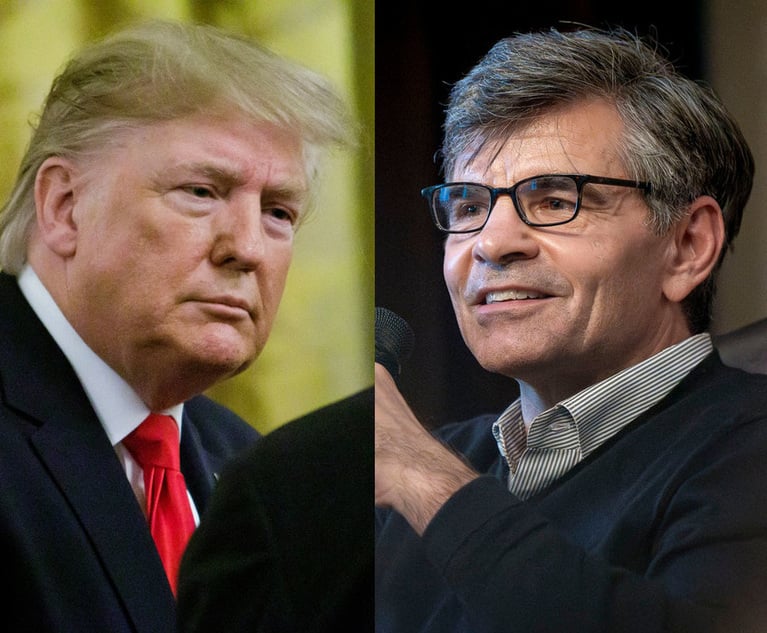

ABC's $16M Settlement With Trump Sets Bad Precedent in Uncertain Times

8 minute read

As Trafficking, Hate Crimes Rise in NJ, State's Federal Delegation Must Weigh in On New UN Proposal

4 minute read

Appellate Court's Decision on Public Employee Pension Eligibility Helps the Judiciary

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Federal Judge Pauses Trump Funding Freeze as Democratic AGs Launch Defensive Measure

- 2Class Action Litigator Tapped to Lead Shook, Hardy & Bacon's Houston Office

- 3Arizona Supreme Court Presses Pause on KPMG's Bid to Deliver Legal Services

- 4Bill Would Consolidate Antitrust Enforcement Under DOJ

- 5Cornell Tech Expands Law, Technology and Entrepreneurship Masters of Law Program to Part Time Format

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250