A Powerful Challenge to Gerrymanders: 'Common Cause v. Rucho'

OP-ED: The record contains indisputable evidence that the 2016 congressional redistricting plan was adopted with an intent to discriminate against Democratic candidates,

February 25, 2019 at 09:00 AM

9 minute read

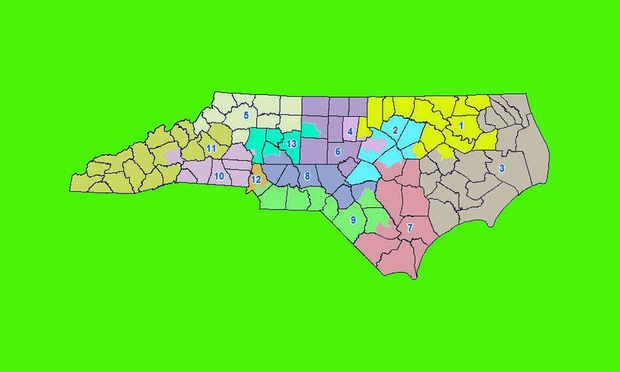

North Carolina 2016 Congressional Redistricting Map.

North Carolina 2016 Congressional Redistricting Map.

Until now, the United States Supreme Court has not agreed on a workable standard to determine the constitutionality of partisan gerrymanders. After March 26, 2019, the date for oral argument in Common Cause v. Rucho, the court could decide that it no longer can adjudicate partisan gerrymanders without a clear standard. That is because the 2017 North Carolina Congressional gerrymander in Rucho may well be the most indefensible partisan gerrymander ever exposed to the court's review.

The 2016 redistricting plan at issue in Rucho was adopted to replace a 2011 Congressional districting plan overseen by State Senator Robert Rucho and State Representative David Lewis, the architects of the 2016 plan. Trial testimony revealed that the goal of Rucho and Lewis in adopting the 2011 plan was “to create as many districts as possible in which GOP candidates would be able to successfully compete for office.”

The 2011 plan achieved that goal. In 2012, GOP candidates received 49 percent of the statewide vote but won nine out of 13 congressional seats. In 2014, GOP candidates won 54 percent of the statewide vote, and won 10 out of 13 seats. Two districts created by that plan, however, were invalidated as racial gerrymanders in 2016 by a three-judge District Court that enjoined their use in future elections, creating the necessity for the 2016 plan.

Rucho and Lewis hired Dr. Thomas Hofeller, a redistricting expert, to draw the 2016 plan. They instructed him to maintain the existing partisan markup of the state's congressional delegation (10-3 GOP). They also instructed him “to change as few” of the 2011 district lines as possible. Dr. Hofeller testified that “partisanship considerations” were the principal factor governing his efforts.

Dr. Hofeller completed his work on the 2016 plan on Feb. 13, 2016. On Feb. 16, a Joint Select Committee on Congressional Redistricting met for the first time and adopted criteria for the 2016 plan. One of the criteria, entitled “Partisan Advantage,” adopted on a party-line vote, stated that: “[T]he committee shall make reasonable efforts to construct districts in the 2016 *** Plan to maintain the current (10-3) partisan makeup of North Carolina's congressional delegation.”

The North Carolina House of Representatives and Senate, on party-line votes, approved the plan. During the House debate, Representative Lewis explained his rationale for the 2016 Plan: “I think electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to help foster what's best for the country.”

In November 2016, North Carolina held congressional elections under the 2016 plan. Republican candidates for Congress received 53.22 percent of the statewide vote but won election in 10 of the 13 (76.92 percent) districts. Similarly, in the 2018 election, Republicans received 50.39 percent of the vote and won 10 of the 13 seats, although the results in District 9 have been challenged.

Common Cause, the North Carolina Democratic Party and the League of Women Voters challenged the 2016 plan as an unconstitutional gerrymander in violation of the Equal Protection Clause; the First Amendment; and Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution. In January 2018, a three-judge District Court struck down the plan as unconstitutional. In June 2018 the United States Supreme Court vacated on standing grounds the District Court's judgment, remanding the matter for reconsideration in light of Gill v. Whitford, a decision that addressed the evidence required to establish standing to assert partisan gerrymandering claims under the Equal Protection Clause.

The practice of partisan gerrymandering has gained significant attention in recent years, and frequently is cited as a primary cause of our national political polarization. The reason is clear. If election districts are gerrymandered on a partisan basis, they are drawn to be safe for candidates of the party that engineered the gerrymander. Once elected, those candidates usually have safe seats until the next redistricting cycle, which means that they typically face little risk in the general election. But because the gerrymander does not insulate them from a primary challenge, their main risk of losing their safe seat is in the primary, with Republicans often facing challenges from more conservative candidates, and Democrats from more liberal candidates. Accordingly, incumbent Republicans tend to adhere to conservative policies to guard against primary challenges on their right, and incumbent Democrats adhere to liberal policies to avoid primary challenges on their left. The result is a loss of moderate representation from either party in both national and state elected office.

The Supreme Court's splintered partisan gerrymandering jurisprudence dates back to its 1986 decision in Davis v. Bandemer, an appeal from a decision invalidating a 1981 Indiana State legislative redistricting map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. On appeal, three justices would have reversed on the ground that partisan gerrymandering claims by political parties present a nonjusticiable political question. Four Justices voted to reverse on the ground that the evidence did not support a finding that the gerrymander had a discriminatory effect on Indiana Democrats. The plurality opinion by Justice White held that to establish that a partisan gerrymander had an unconstitutional discriminatory effect, a plaintiff must prove that the aggrieved political party “has been unconstitutionally denied its chance to participate in the political process,” or that the “electoral system [has been] arranged in a manner that will consistently degrade a voter's or a group of voters' influence on the political process as a whole.” That test proved impossible for future plaintiffs to satisfy. As one commentator explained, “by its impossibly high proof requirements the Court in Bandemer essentially eliminated political gerrymandering as a … cause of action, but only after it had declared the process unconstitutional.”

In its 2004 decision in Veith v. Jubilerer, a divided Supreme Court dismissed a partisan gerrymandering challenge to a Pennsylvania Congressional redistricting plan. Four justices would have held the claim to be non-justiciable and overruled Davis v. Bandemer. Justice Kennedy found the claim to be justiciable, was unsure about the standard, but joined the plurality in voting to dismiss the complaint. Justices Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg and Breyer all concluded that the claim was justiciable, but proposed different standards for adjudicating the plaintiffs' gerrymander claim. The apparent result of the decision in Veith is that the Davis v. Bandemer standard was not overruled, although none of the Justices in Veith supported it.

The Fourth Circuit, in its August 2018 decision in Common Cause v. Rucho, which the Supreme Court will review, concluded that the 2016 North Carolina redistricting plan clearly was unconstitutional, and that it violated the First Amendment, Article 1 of the Constitution, and the Equal Protection Clause. Concerning the First Amendment claim, the court found that the North Carolina legislature, in enacting the 2016 plan, predominately intended to “burden the speech and associational rights” of entities and voters likely to support non-Republican candidates.

Concerning Article I, Section 2, the court held that the Elections Clause did not authorize the North Carolina Legislature to disfavor the interests of the Democratic Party and its candidates, and that the 2016 plan was an impermissible effort to “dictate electoral outcomes” and “disfavor a class of candidates.”

Most significantly, the court found that the 2016 plan violated the Equal Protection Clause. In doing so, it became the first Court of Appeals to rely on the “efficiency gap,” a newly minted measure of partisan asymmetry developed at the University of Chicago. The efficiency gap quantifies the difference in wasted votes between two parties in an election, dividing that difference by the total number of votes cast to calculate a percentage that constitutes the efficiency gap. As the Fourth Circuit explained:

“Wasted” votes are votes cast for a candidate in excess of what the candidate needed to win a given district, which increase as more candidates are “packed” into the district, or votes cast for a losing candidate in a given district, which increase *** when [his] party's supporters are cracked.

Using the results of the 2016 elections under the 2016 plan, plaintiffs' expert, Dr. Simon Jackman, calculated an efficiency gap favoring GOP candidates of 19.4 percent. Comparing that percentage with his comparative calculation of efficiency gaps based on redistricting plans for 512 congressional elections in 25 states from 1972 to 2016, Dr. Jackman found that 95 percent of the plans in that database yielded smaller efficiency gaps than that produced by the 2016 plan. Dr. Jackman also calculated the efficiency gaps for congressional districting plans for 24 states for which his database contained 2016 data, and found that the North Carolina plan's efficiency gap was the largest.

Although the Fourth Circuit relied on other statistical measures to support its Equal Protection analysis, the use of the efficiency gap data distinguishes Rucho from earlier partisan gerrymandering cases. By recognizing that wasting the disfavored parties' votes is the critical goal of a successful gerrymander, and then comparing the wasted votes of the two parties in an election to calculate the efficiency gap, the Fourth Circuit responded to the Supreme Court's conservative wing's demand for an objective standard to evaluate the constitutionality of a partisan gerrymander. The greater the disparity in wasted votes between the parties, the higher the efficiency gap percentage.

Given the court's conservative majority, no one should assume that the Rucho decision will be affirmed. But the record contains indisputable evidence that the 2016 plan was adopted with an intent to discriminate against Democratic candidates, and the efficiency gap calculation offers the court a persuasive and understandable measurement for comparing partisan gerrymanders and identifying those that are unconstitutionally extreme.

Retired Justice Gary S. Stein served on the New Jersey Supreme Court from 1985-2002 and is counsel to Pashman Stein Walder Hayden in Hackensack. He teaches Election Law at Rutgers Law School-Newark.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Send Us Your New Partners for the NJ Law Journal's New Partners Yearbook

1 minute read

New Methods for Clients and Families to Have Their Estate and Legacy Planning Complete

5 minute read

Tensions Run High at Final Hearing Before Manhattan Congestion Pricing Takes Effect

4 minute readTrending Stories

- 1'It's Not Going to Be Pretty': PayPal, Capital One Face Novel Class Actions Over 'Poaching' Commissions Owed Influencers

- 211th Circuit Rejects Trump's Emergency Request as DOJ Prepares to Release Special Counsel's Final Report

- 3Supreme Court Takes Up Challenge to ACA Task Force

- 4'Tragedy of Unspeakable Proportions:' Could Edison, DWP, Face Lawsuits Over LA Wildfires?

- 5Meta Pulls Plug on DEI Programs

Who Got The Work

Michael G. Bongiorno, Andrew Scott Dulberg and Elizabeth E. Driscoll from Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr have stepped in to represent Symbotic Inc., an A.I.-enabled technology platform that focuses on increasing supply chain efficiency, and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The case, filed Oct. 2 in Massachusetts District Court by the Brown Law Firm on behalf of Stephen Austen, accuses certain officers and directors of misleading investors in regard to Symbotic's potential for margin growth by failing to disclose that the company was not equipped to timely deploy its systems or manage expenses through project delays. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton, is 1:24-cv-12522, Austen v. Cohen et al.

Who Got The Work

Edmund Polubinski and Marie Killmond of Davis Polk & Wardwell have entered appearances for data platform software development company MongoDB and other defendants in a pending shareholder derivative lawsuit. The action, filed Oct. 7 in New York Southern District Court by the Brown Law Firm, accuses the company's directors and/or officers of falsely expressing confidence in the company’s restructuring of its sales incentive plan and downplaying the severity of decreases in its upfront commitments. The case is 1:24-cv-07594, Roy v. Ittycheria et al.

Who Got The Work

Amy O. Bruchs and Kurt F. Ellison of Michael Best & Friedrich have entered appearances for Epic Systems Corp. in a pending employment discrimination lawsuit. The suit was filed Sept. 7 in Wisconsin Western District Court by Levine Eisberner LLC and Siri & Glimstad on behalf of a project manager who claims that he was wrongfully terminated after applying for a religious exemption to the defendant's COVID-19 vaccine mandate. The case, assigned to U.S. Magistrate Judge Anita Marie Boor, is 3:24-cv-00630, Secker, Nathan v. Epic Systems Corporation.

Who Got The Work

David X. Sullivan, Thomas J. Finn and Gregory A. Hall from McCarter & English have entered appearances for Sunrun Installation Services in a pending civil rights lawsuit. The complaint was filed Sept. 4 in Connecticut District Court by attorney Robert M. Berke on behalf of former employee George Edward Steins, who was arrested and charged with employing an unregistered home improvement salesperson. The complaint alleges that had Sunrun informed the Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection that the plaintiff's employment had ended in 2017 and that he no longer held Sunrun's home improvement contractor license, he would not have been hit with charges, which were dismissed in May 2024. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Jeffrey A. Meyer, is 3:24-cv-01423, Steins v. Sunrun, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Greenberg Traurig shareholder Joshua L. Raskin has entered an appearance for boohoo.com UK Ltd. in a pending patent infringement lawsuit. The suit, filed Sept. 3 in Texas Eastern District Court by Rozier Hardt McDonough on behalf of Alto Dynamics, asserts five patents related to an online shopping platform. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Rodney Gilstrap, is 2:24-cv-00719, Alto Dynamics, LLC v. boohoo.com UK Limited.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250