Busy Women Lawyers Are Freezing Eggs and Embryos to Manage Careers

Jacqueline Klosek, a New Jersey resident and counsel to Goodwin Procter's business law department in New York, said, "it would have been really hard to get the career off track and assume I could get it back on.”

March 01, 2019 at 05:45 PM

7 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Law.com

Elizabeth Brown of Rosenberg & Estis. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Elizabeth Brown of Rosenberg & Estis. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Elizabeth Brown, 29, an associate at Rosenberg & Estis in New York, and two of her best friends are seriously considering freezing their eggs in the next few years if they're still single. She said she loves her job and doesn't want to tear herself away from it.

“Knowing that you can freeze your eggs, it takes so much of the pressure off,” she says of being able to focus on her career instead of going on dates every night. “I value my time and would rather go home and have a glass of wine and watch Netflix than go on a random date because I feel like I should be having kids in the next few years.”

When Brown was in her third year at Yeshiva University Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine removed the experimental label from oocyte cryopreservation—or egg freezing. The idea that it was possible to freeze eggs—rather than embryos—changed the way that women thought about childbearing and ushered in what fertility specialists are calling a new era of reproductive autonomy. The takeaway: women can have a child from their own egg as late as age 56.

Lawyers, of course, weren't the only ones to flock to preserve their eggs. But experts say they were more likely to do so because they could afford the $20,000 to $30,000 in out-of-pocket costs for the medicine to stimulate egg production, the extraction of the eggs, the storage fees and in vitro fertilization.

Plus, the long career path from college to law school to the bar exam to a clerkship, an in-house job or a stint in the U.S. Attorney's office meant that lawyers often reached their prime childbearing ages just as they were establishing themselves at law firms. Brown, for instance, arrived at Rosenberg & Estis in the summer of 2018 after an in-house counsel job.

Jacqueline Klosek of Goodwin.

Jacqueline Klosek of Goodwin. Jacqueline Klosek, a New Jersey resident and counsel to Goodwin Procter's business law department in New York, said, “it would have been really hard to get the career off track and assume I could get it back on” if she had wanted to become pregnant at an earlier age. By her late 30s when her gynecologist asked her if she wanted a family, she was still ambivalent. “I honestly wasn't sure whether I wanted to have children, but I wanted to keep my options open,” she said.

So she went on medication to stimulate her ovaries to produce multiple eggs at the age of 38 and ended up with 30. Because she had a boyfriend with whom she had a serious relationship, her doctor suggested that she divide the eggs, fertilizing half to create frozen embryos and leaving the rest unfertilized in case she chose to have children with a different mate. (Doctors prefer freezing embryos to eggs when that's an option because they are more stable and can be tested for abnormalities.)

Klosek did end up staying with her boyfriend, Tom Lozinski, who is now her husband, and they conceived Kayla six years ago. But three years later, Klosek wasn't able to get pregnant a second time, and she had one of the frozen embryos implanted. Luca is now 2.

What would have happened if the gynecologist hadn't asked that fateful question?

“Thinking that I could not have my son I couldn't even think about that,” she says. “To have missed that because I waited too long would have been really hard to accept.”

Until the last five years, lawyers like Klosek and Brown would be unlikely to see a fertility specialist unless they were having trouble becoming pregnant. Stories abound of an earlier generation of lawyers who found themselves unable to conceive because they were too old by the time they sought help.

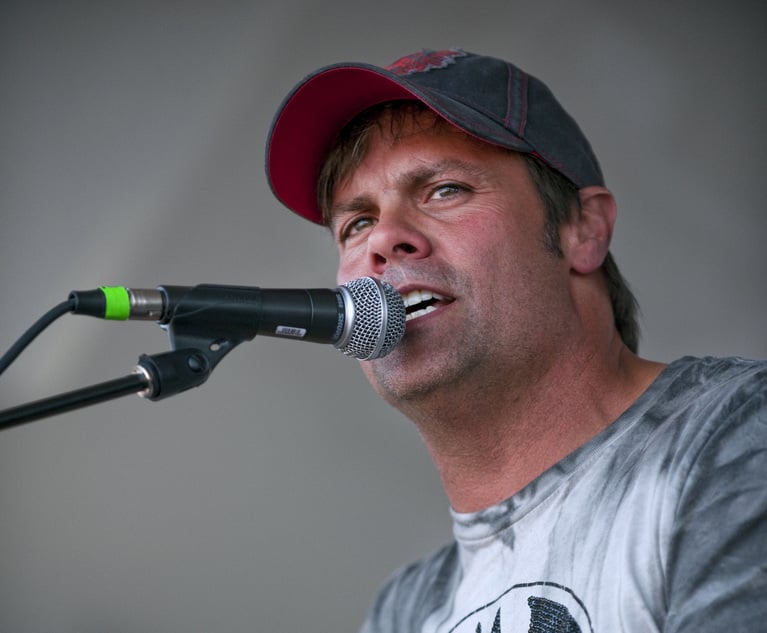

Dr. Alan Copperman. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Dr. Alan Copperman. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ “For decades a lot of young lawyers have missed opportunities to build families and this technology puts that ability back into their hands,” said Dr. Alan Copperman, director of the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Mount Sinai Health System. “When I started practicing 25 years ago I was seeing a lot of 40-year-olds who had missed their opportunities to have families and I could only do so much for them.”

Copperman, who is also the medical director of RMA of New York, said he sees a lot of lawyers especially from the firms near the fertility clinic's offices at 59th Street and Madison Avenue. “Just as a birth control pill is great at preventing unwanted pregnancy, egg freezing is really getting pretty good at enabling wanted pregnancy,” he says.

He suggests that lawyers who are not ready to start families after law school have fertility checkups in their twenties. This involves a family history, a pelvic ultrasound and a blood test for the anti-mullerian hormone, which is an indicator of how many eggs still remain in the ovarian reserve. More eggs must be extracted if a woman is older when she chooses to extract them because 90 percent of eggs are normal in her twenties but 90 percent are abnormal by her forties.

“So whether someone has cancer and they're about to have chemotherapy or whether someone is 39 and they're about to be 40 this is a medical condition,” Copperman says. “Medically we're preventing disease.”

Even though Copperman sees it as a medical procedure, that doesn't mean that traditional insurance companies are covering egg freezing. It was estimated in 2017 that 5 percent of companies, including Facebook and Uber, are making it an employment benefit and Copperman said the list is growing.

Lab supervisor Rose Marie Roth with canisters of frozen, stored human eggs in the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science at the Mount Sinai Health System. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJ

Lab supervisor Rose Marie Roth with canisters of frozen, stored human eggs in the department of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive science at the Mount Sinai Health System. Photo: David Handschuh/NYLJBut there are detractors.

Cynthia Thomas Calvert, senior adviser for Family Responsibilities Discrimination at The Center for WorkLife Law at UC Hastings College of the Law, thinks egg freezing is “a bandaid” for lawyers.

“If it catches on and becomes the solution to the long hours culture it gives the law firms a pass. It allows them to take their foot off the gas and not find a solution that helps men and women find balance. This might really be a step backward if it takes some urgency out of those issues.” she says.

“Are you doing this because you truly love your job?” Lauren Stiller Rikleen, an attorney who is the founder and president of the Rikleen Institute for Strategic Leadership, asks women who are considering egg freezing. “Then I think that's what science and choice should be about. But what I worry about with respect to young women that they do it from a fear that if they get pregnant earlier they will be perceived as not committed to their careers.”

While there have been tens of thousands of babies born from frozen eggs, even the supporters stress it won't work for everyone.

“This isn't life insurance. This isn't flood insurance. What we're trying to do is change a woman's reproductive trajectory,” Copperman says.

Read More:

Women Lawyers Deploy Tactical Maneuvers to Handle Child Care

Data Snapshot: Is Big Law Making Progress On Gender Diversity?

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

On the Move and After Hours: Einhorn Barbarito; Gibbons; Greenbaum Rowe; Pro Bono Partnership

4 minute read

Engine Manufacturer Escapes Suit Over NJ Helicopter Crash That Killed Country Music Star

3 minute readTrending Stories

- 1ACC CLO Survey Waves Warning Flags for Boards

- 2States Accuse Trump of Thwarting Court's Funding Restoration Order

- 3Microsoft Becomes Latest Tech Company to Face Claims of Stealing Marketing Commissions From Influencers

- 4Coral Gables Attorney Busted for Stalking Lawyer

- 5Trump's DOJ Delays Releasing Jan. 6 FBI Agents List Under Consent Order

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250