Mesh Plaintiffs Leadership Hits Back at Mazie Slater, Other Fee Objectors

On Monday, Henry Garrard, chairman of the fee and cost committee, fired back at four law firms objecting to their share of an estimated $550 million in common benefit fees.

April 10, 2019 at 10:45 AM

8 minute read

The original version of this story was published on Law.com

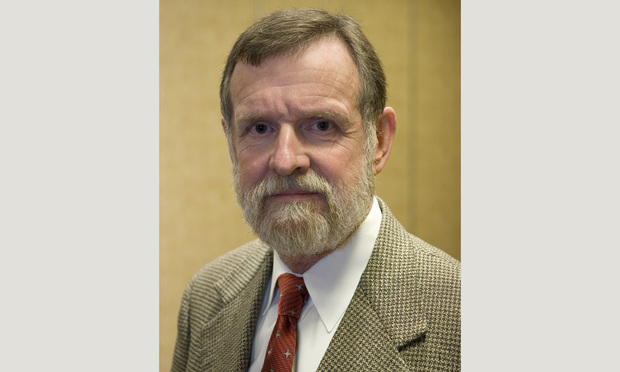

Henry G. Garrard III of Blasingame, Burch, Garrard & Ashley. Photo: Zachary D. Porter/ALM

Henry G. Garrard III of Blasingame, Burch, Garrard & Ashley. Photo: Zachary D. Porter/ALM

Lead plaintiffs' attorneys in the transvaginal mesh litigation have fired back at New Jersey's Mazie Slater Katz & Freeman and three other law firms objecting to their share of an estimated $550 million in fees, accusing the firms of collectively making false attacks and submitting bills “riddled with excessive entries, duplicative billing” and other problems.

In a Monday filing, Henry Garrard III, chairman of the fee and cost committee, said all four firms failed to demonstrate how their work contributed to the “common benefit” of all lawyers in the litigation over transvaginal mesh device.

“The objectors focus much of their objections on attacking the FCC and its members and the external review specialist and complaining of information they were allegedly not provided about other firms' submissions,” Garrard wrote in Monday's response to the objections. “However, the objectors do little to explain how and why the work they claim to have performed that the FCC questioned or did not recognize should be considered for the common benefit of the MDL plaintiffs, or why the FCC's valuation of their contributions to the MDL is allegedly wrong.”

In fact, he wrote, many of the submissions were “riddled with excessive entries, duplicative billing, vague or inadequate descriptions of work claimed” and other timekeeping problems.

Garrard, a shareholder at Blasingame, Burch, Garrard & Ashley in Athens, Georgia, also disputed allegations of self-dealing and bill padding against law firms on the fee and cost committee.

In its objection, Mazie Slater had accused plaintiffs' attorney Bryan Aylstock of pressuring Garrard to boost the fees to his firm, Aylstock, Witkin, Kreis & Overholtz in Pensacola, Florida. Aylstock allegedly threatened that his fellow partner, Renée Baggett, who serves on the committee, would not sign off on its preliminary written recommendation without the increase. Aylstock Witkin eventually received more than $27 million in common benefit fees.

In Monday's filing, Garrard called the account false, stating that he “has never felt taken advantage of by this firm.”

“The FCC evaluated the Aylstock firm's submission by the same criteria as every other firm, which included the opportunity to provide and receive feedback and to be heard,” he wrote.

The use of such “caustic rhetoric” was “unfortunate,” he added.

“It serves no legitimate purpose for these objectors to air personal grievances or what they apparently believe to be 'dirty laundry' regarding alleged conversations with FCC members or with the external review specialist save perhaps to embarrass or insult,” he wrote.

He noted that the eight firms on the fee and cost committee were lead attorneys in the litigation from the start. In a footnote, he mentioned that a financial adviser also served on the fee and cost committee. “If there had been any attempt to subvert the process set forth by the court in its prior orders by anyone on the FCC, this court would have been made aware,” he wrote in the footnote. “There was not.”

Mazie Slater, based in Roseland, is one of four law firms objecting to the fees, paid to 94 law firms involved in more than 100,000 lawsuits over the devices, most of them coordinated in multidistrict litigation in federal court in West Virginia.

The fee and cost committee filed its final allocation recommendations March 12 (see chart), as did an “external review specialist,” Daniel Stack, a retired judge on the Madison County, Illinois, Circuit Court, who was appointed to review the fee allocation process.

The Mazie firm's Adam Slater did not respond to a request for comment.

The other objectors are Philadelphia's Kline & Specter, New York's Bernstein Liebhard and Anderson Law Offices in Cleveland. Bernstein Liebhard partners Stanley Bernstein and Sandy Liebhard, and Ben Anderson, of Anderson Law Offices, did not respond to requests for comment.

Shanin Specter, of Kline & Specter, stood by his claims in an email.

“Our record of six trial victories—the most in this litigation—is ignored by the fee committee,” he wrote. “Instead, they resort to personal attack. And disturbingly, they don't contest the substantial evidence of fraudulent billing and improper influence of and wrongful conduct by a court appointed officer, which casts a dark shadow on these proceedings.”

Many of the objecting law firms had sought compensation for work related to a New Jersey trial, in which an Atlantic County Superior Court jury came out with an $11 million verdict against Johnson & Johnson's Ethicon Inc. in 2013.

Some cited a 2012 agreement under which the MDL leadership vowed to have a representative of the New Jersey cases on the fee and cost committee and “use their best efforts to ensure that the MDL court fairly compensates the aforesaid common benefit work.”

In Monday's response, Garrard said the firms overstated the significance of that agreement.

He also called complaints that the fee and cost committee had not been transparent in the allocation process “baseless,” noting that the objectors had multiple opportunities to bring up their concerns with the fee committee or Stack.

“What is characterized by objectors as disproportionate is no different than what has been reflected in numerous other common benefit allocations: the firms who take on the most responsibility, who lead and oversee the litigation generally who devote the most resources and bear the most financial risk, and whose contributions were most valuable to the benefit of all MDL plaintiffs, receive the largest common benefit allocations,” Garrard wrote.

Here's what the fee committee had to say about each of the objecting firms:

➤ Mazie Slater, objecting to $6.02 million in fees, claimed to be “one of the driving forces” of the mesh litigation, filing the first case in the country against Ethicon in 2008. But the fee committee found that the firm's work was limited to a single product. “The firm did very little or nothing related to any other product or manufacturer that could be considered common benefit,” Garrard wrote. The committee also attached to Monday's filing a common benefit order in the mesh lawsuits in New Jersey in which Mazie Slater received fees for its work. “Mazie Slater's timekeeping records were also largely indecipherable, making the FCC's task exceedingly difficult,” the committee added, noting time entries that “were so vague as to be meaningless.”

➤ Kline & Specter, objecting to $3.7 million in fees, sought compensation based on six verdicts the firm obtained for plaintiffs totaling more than $146 million, all in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas. It also claimed to assist in the New Jersey trial. But the committee found that the firm “has done very little work that could be considered for the common benefit” and, instead, was a beneficiary of work done by other lawyers. The committee also criticized the firm's “campaign of denigration and harassment.”

“By causing unnecessary delay and expense and by seeking to diminish the amount of the common benefit award available to all applicant counsel simply because it feels slighted, KS has been a common detriment,” Garrard wrote. “This sort of behavior would warrant a reduction in its allocation rather than any increase.”

➤ Bernstein Liebhard, which is based in New York City, objecting to $942,000 in fees, had insisted that its former partner, Jeff Grand, “played a significant role” in both the New Jersey trial and in the multidistrict litigation against Ethicon. The fee committee, however, found that Grand, now at Seeger Weiss, “played a limited supporting role in four Ethicon cases that were tried by other firms.”

➤ Anderson Law Offices, awarded $7.2 million in fees, sought compensation for its work in the New Jersey trial and, more generally, in litigation against Ethicon. The fee committee said, “Anderson devotes comparatively little of his objection to explaining what he did in the litigation,” instead “criticizing the FCC, the external review specialist, or the allocation process generally.” The committee also accused the firm of duplicative and excessive billing. “Anderson's submissions are either reflective of an egregiously ineffective and inefficient use of time, or else they are exaggerated—pure and simple,” he wrote.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Social Media Policy for Judges Provides Guidance in a Changing World

3 minute read

Bank of America's Cash Sweep Program Attracts New Legal Fire in Class Action

3 minute read

'Something Really Bad Happened': J&J's Talc Bankruptcy Vote Under Attack

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Avantia Publicly Announces Agentic AI Platform Ava

- 2Shifting Sands: May a Court Properly Order the Sale of the Marital Residence During a Divorce’s Pendency?

- 3Joint Custody Awards in New York – The Current Rule

- 4Paul Hastings, Recruiting From Davis Polk, Continues Finance Practice Build

- 5Chancery: Common Stock Worthless in 'Jacobson v. Akademos' and Transaction Was Entirely Fair

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250