Snap Removals Must Be Addressed

We think that the validation of this kind of gamesmanship by two Courts of Appeals perfectly illustrates the 1947 caution of Judge Learned Hand against the plain meaning doctrine of statutory construction.

December 01, 2019 at 10:00 AM

5 minute read

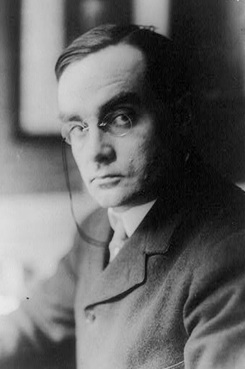

Judge Billings Learned Hand / Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Judge Billings Learned Hand / Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Since the Judiciary Act of 1789, defendants have been able to remove to federal court state court suits over which the district court would have diversity of citizenship jurisdiction if it had been filed there. Removal is accomplished simply by the defendant timely e-filing in the district court of a notice of removal, signed under Rule 11, that states the basis for federal jurisdiction and attaches a copy of the state court pleadings.

Since the revision of Title 28 in 1948, however, 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b)(2) has limited diversity removal to suits against an out of state defendant by providing that an action otherwise removable solely on the basis of diversity "may not be removed if any of the parties in interest properly joined and served is a citizen of the state where the action is brought." The rationale of the restriction is that diversity jurisdiction is only necessary to protect out-of-state defendants from potential local prejudice in the state courts, and that a defendant sued in its home state therefore does not need to burden the federal courts.

Back in the day of paper filing, most defendants didn't learn they had been sued until they were served with process. The "properly joined and served" language of § 1441(b) operated only to prevent a plaintiff from defeating diversity removal by joining an in-state defendant that it did not intend to proceed against and therefore did not serve. But electronic filing in the state courts has now changed all that. It is possible for a sophisticated business to continually monitor the state court docket for its own name and learn that it has been sued before it is served. In-state defendants who would prefer what they consider to be the shelter of the federal courts have developed the practice of what is called "snap removal," in which they monitor the docket and then avoid service of process long enough to remove cases brought by out of state plaintiffs. The removal is then challenged by the plaintiff's motion to remand. Snap removal is a particularly important tactical device for businesses that can expect a significant number of product liability suits against them in the courts of the state where they have their headquarters or principal place of business.

The district courts have been sharply divided about the legality of snap removal. Some, including in the District of New Jersey, held that it led to a "bizarre result" that defeated Congress's intent to keep in-state defendants from removing based on diversity. Others relied on the literal language of the statute to uphold snap removal before the in-state defendant was served. Two recent Court of Appeals decisions, by the Third Circuit in 2018 and the Second Circuit this year, have come down squarely on the side of plain meaning, denying motions to remand and holding that the statute allows an in-state defendant to remove as long as it can file in federal court before it has been "properly served." Insofar as the result is bad public policy, they state, the remedy lies with Congress.

The Third Circuit believed that this interpretation was acceptable because snap removal is possible "only in the narrow circumstances where a defendant is aware of an action prior to service of process with sufficient time to initiate removal." That circumstance isn't so narrow. As this paper reported recently, the result has been a practice of sophisticated defendants vigilantly monitoring the state court electronic docket and then ducking service until they can remove. We don't believe that this result is consistent with Congress's overriding intent to keep in-state defendants from invoking diversity jurisdiction.

Congress may fix the problem or it may not. There are hearings pending on proposed legislation, and this might be the kind of technical issue on which our deeply polarized representatives can find sensible common ground.

In the meantime, though, we think that the validation of this kind of gamesmanship by the two Courts of Appeals perfectly illustrates the 1947 caution of Judge Learned Hand in Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co. v. Commissioner against the plain meaning doctrine of statutory construction:

"There is no more likely way to misapprehend the meaning of language … than to read the words literally, forgetting the object which the document as a whole is meant to secure. Nor is a court ever less likely to do its duty than when, with an obsequious show of submission, it disregards the overriding purpose because the the particular occasion which has arisen was not foreseen."

The unforeseen development of electronic filing has allowed a class of defendants to get into federal court whom the drafters of § 1441(b) in 1948 would never have wanted there, but the current judicial style of statutory construction is far more passive-aggressive towards the legislature and far more limited in its concept of judicial duty to make things work sensibly than it was in Judge Hand's day.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Social Media Policy for Judges Provides Guidance in a Changing World

3 minute read

Bank of America's Cash Sweep Program Attracts New Legal Fire in Class Action

3 minute read

'Something Really Bad Happened': J&J's Talc Bankruptcy Vote Under Attack

7 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Law Firms Expand Scope of Immigration Expertise, Amid Blitz of Trump Orders

- 2Latest Boutique Combination in Florida Continues Am Law 200 Merger Activity

- 3Sarno da Costa D’Aniello Maceri LLC Announces Addition of New Office in Eatontown, NJ, and Named Partner

- 4Friday Newspaper

- 5Public Notices/Calendars

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250