George Floyd, and What to Do Next

If we are not to go through this crisis again, we need to take concrete measures to weed out abusive officers and to strengthen the political control of the policed over those who police them.

June 19, 2020 at 05:49 PM

6 minute read

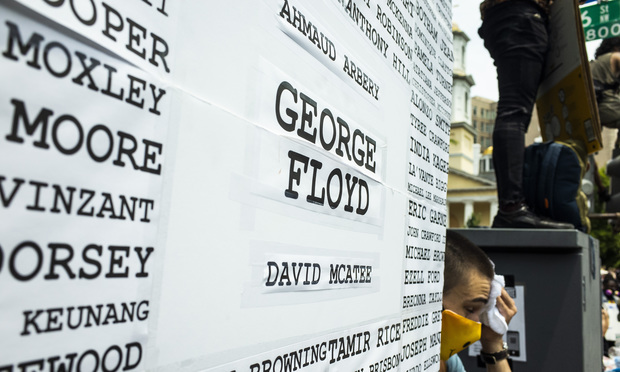

Thousands march in Washington, D.C. protesting police brutality and the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota at the hands of local police, on Saturday, June 6, 2020. Derek Chauvin, the police officer that was caught on video kneeling on Floyd's neck for nearly 9 minutes as the unarmed, handcuffed man laid flat and unable to breathe, has been charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Mass demonstrations have taken place nationwide since the incident took place.

Thousands march in Washington, D.C. protesting police brutality and the killing of George Floyd in Minnesota at the hands of local police, on Saturday, June 6, 2020. Derek Chauvin, the police officer that was caught on video kneeling on Floyd's neck for nearly 9 minutes as the unarmed, handcuffed man laid flat and unable to breathe, has been charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Mass demonstrations have taken place nationwide since the incident took place.

A black man arrested for allegedly passing a $20 counterfeit bill, was killed by a white police officer on a Minneapolis street. The officer pressed his knee against the neck of his prone and handcuffed prisoner for 8 minutes 46 seconds. The officer's head was up, his shoulders back, and his hand in his trouser pocket. There was no resistance. The prisoner, George Floyd, cried out for air and died. Even then, the officer's knee was not removed.

Three other police officers watched George Floyd die. They did nothing but stop an onlooker from intervening. Two autopsies found Floyd's death a homicide. The killer, who had previously been involved in three police shootings, one fatal, was eventually charged with second degree murder. The three onlooking officers were charged as accessories. All four officers were fired.

A bystander captured the scene on video. It quickly went viral on social media. Mass protest demonstrations, mostly peaceful, followed in Minneapolis, in hundreds of other American cities and towns, and elsewhere around the world. Protest signs included "I CAN'T BREATHE." Elected officials expressed sympathy and called for calm, but at the working level, it all too often looked like the police thought they were dealing with an uprising that had to be suppressed. In a sense, they were. The demonstrations are a cry of rage against the normal model of urban policing, which rests on the assumption that the nonwhite public is intrinsically dangerous and must be kept under control. More than 40 years ago, the NYPD's Bronx Borough Commander regretfully called himself the "commander of an army of occupation of the ghetto," lamenting that his force was tasked to keep unsolved fundamental problems of poverty and racism from boiling over. This uprising tells us that nothing much has changed. And far too many policemen over the years have bought into the "army of occupation" model without regret. It is no accident that the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis announced that it "will provide full support to the involved officers." The police union's president denounced the firing of the four officers as "despicable behavior."

At some point, protest demonstrations come to an end until the next brutal incident revives them. Promises made during protests are forgotten. Municipal and other governmental authorities that control police operations, sometimes with good intentions, defer to those who encounter danger to protect the public safety – and to police unions. If we are not to go through this crisis again, we need to take concrete measures to weed out abusive officers and to strengthen the political control of the policed over those who police them. Those measures include enhanced screening, enhanced discipline, and enhanced liability for abuse by police authorities. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature consider the following:

• Police officers should be licensed, as they are in 43 states. New Jersey already requires minimum uniform standards of training and psychological screening. These should be strengthened. The license requirement will allow the state to remove officers with a record of abuse and to prevent their being hired in some other municipality. In this connection, there should be a publicly available database of use of force complaints against police officers and their dispositions.

• The Legislature should enact a uniform system of police discipline, which meets minimum constitutional standards of due process and is not subject to collective bargaining. The disciplinary authority should be outside the police department. Preferably, it should be under the direct control of the state government.

• The Department of Law and Public Safety should promulgate or be required to promulgate uniform standards for the use of force. These should include an examination of the need to arrest for non-violent offenses instead of using summonses. Choke holds and neck holds should be outlawed.

• There should be a reexamination of the community caretaker function of the police, who are too often the first resort, last resort or only resort of municipal government for medical, psychological and social interventions that do not or should not require the use of force and can be handled by emergency medical services. New Jersey needs to reimagine the role of police and scale it back. (We will editorialize further on this point.)

• State law on individual and government civil liability for abuse of force should be reexamined. The qualified immunity doctrine is a judicially created limit in federal law for liability for violation of constitutional rights under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. In New Jersey, the Tort Claims Act provides that "A public employee is not liable if he acts in good faith in the execution or enforcement of any law," N.J.S.A. 59:3-3, and an "objectively reasonable" standard is applied. It is time for the legislature to conduct a review and analysis of how qualified immunity has been applied in law enforcement misconduct cases and whether there has been a pattern of denial of meritorious claims. If it is determined that public policy is not being served by current standards, the legislature should consider amendments to the Tort Claims Act and the state Civil Rights Act as they pertain to injury or death allegedly caused by law enforcement, including, but not limited to change to the objectively reasonable standard in the use of force and availability of a res ipsa loquitor-type burden shifting in cases of death in police custody. Consideration should also be given to providing substantial liquidated damages for any wrongful death in police custody.

• Finally, the Legislature should examine police recruitment with the objective of encouraging the police to correspond with the demographics of the local community. The objective is to put on the front line officers who come from the community they patrol, with the judgment to distinguish the dangerous from the merely boisterous, and to use that essential element of the policeman's toolkit, the blind eye.

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

Retiring AOC Director Judge Glenn A. Grant Walks Away From Judiciary 'Tremendously Impressed' by New Jersey's Judges

5 minute readTrending Stories

- 1Absent Explicit Agreement, Court Rejects Unilateral Responsiveness Redaction of Text Messages

- 2SEC Whistleblower Program: What to Expect Under the Trump Administration

- 3Sidley Hires Paul Hastings Energy Finance Partner in Houston

- 4Potential Pitfalls in Arbitrating Religious Disputes

- 5NYAG’s Enforcement of Mandated Cybersecurity Safeguards Sends Expensive Shock Waves through Varying Industries

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250