No Contempt Charges Under Criminal Justice Reform Act, NJ High Court Rules

In a 7-0 decision, the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed an appellate panel's ruling that a defendant who has been released pretrial under the Criminal Justice Reform Act, and subsequently violates a condition of that release, can be charged and prosecuted for criminal contempt by the state.

July 22, 2020 at 08:53 AM

9 minute read

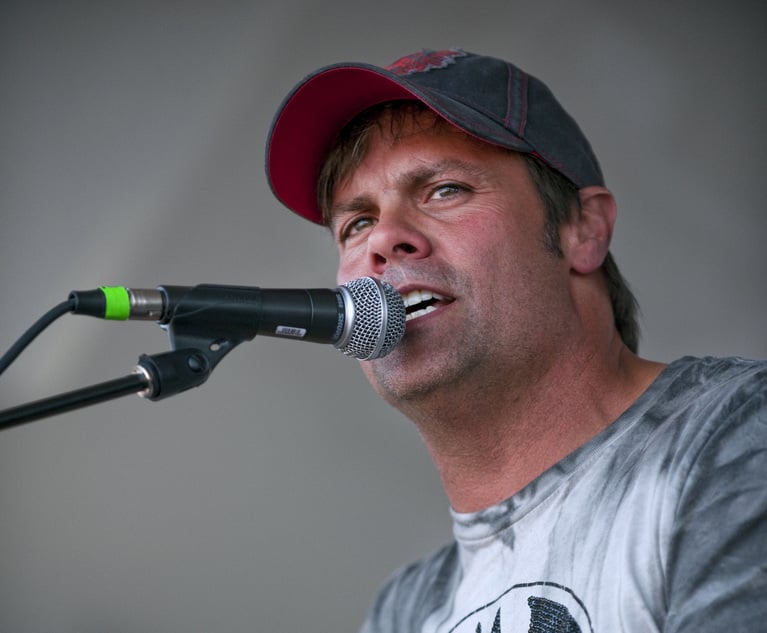

Chief Justice Stuart Rabner of the New Jersey Supreme Court. (Photo: Carmen Natale/ALM)

Chief Justice Stuart Rabner of the New Jersey Supreme Court. (Photo: Carmen Natale/ALM)

In a 7-0 decision, the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed an appellate panel's ruling that a defendant who has been released pretrial under the Criminal Justice Reform Act, and subsequently violates a condition of that release, can be charged and prosecuted for criminal contempt by the state.

In State v. McCray and State v. Gabourel, Chief Justice Stuart Rabner, writing for the court, said such action was at complete odds with the legislative intent of the CJRA. The act took effect on Jan. 1, 2017, under former Gov. Chris Christie and essentially eliminated money bail to make New Jersey's pretrial justice system fairer.

"The history of the CJRA reveals the Legislature did not intend to authorize criminal contempt charges for violations of release conditions," Rabner wrote in the July 20 opinion. "Beyond that, allowing such charges for all violations of conditions of release, no matter how minor, is at odds with the purpose and structure of the CJRA."

Justices Jaynee LaVecchia, Barry Albin, Anne Patterson, Faustino Fernandez-Vina, Lee Solomon and Walter Timpone join in the unanimous decision.

In the two consolidated cases on appeal, both defendants were arrested and released on nonmonetary conditions, pursuant to the CJRA. After allegedly violating those conditions, each defendant was charged with contempt, a fourth-degree offense, for violating a court order.

The state—the plaintiff in both cases—argued there was nothing in the CJRA that precludes contempt prosecutions, which are consistent with the act's purposes and supported by case law in State v. Gandhi.

Both trial court judges concluded the CJRA did not permit the state to pursue contempt charges. But the Appellate Division reversed, based on its review of the statute and its legislative history.

"We largely agree with the trial court rulings," Rabner said in the 28-page opinion.

Rabner said the state misinterpreted the CJRA and that prosecutors cannot charge defendants with criminal contempt for violating any release condition, such as a curfew or court no-show order.

"The Legislature expressly removed the option of contempt proceedings from the original draft of the bill. In doing so, the Legislature parted company with other laws it looked to when it crafted the CJRA," wrote Rabner. "Beyond that, allowing criminal contempt charges for all violations of conditions of release, no matter how minor, is at odds with the purpose and structure of the CJRA."

Rabner said no-contact orders, on the other hand, are treated differently because the CJRA never modified settled law relating to them. Gandhi from 2010, which the court reviewed in detail, plainly set forth that principle, charging that violations of no-contact orders, even if issued as part of a pretrial release order, can serve as a basis for contempt.

"Nothing in the CJRA or its legislative history suggests the Legislature intended to overrule the prevailing law in Gandhi," Rabner said. He alluded to judges who regularly enter orders in domestic violence cases and other matters that bar defendants from contacting witnesses and victims.

"Neither defendant in this appeal was charged with violating a no-contact order. For the reasons outlined above, we reverse the judgment of the Appellate Division and reinstate the orders of the trial court dismissing the contempt charges against both defendants," said Rabner.

The cases were argued on March 2, 2020. Appearing as amici curiae were the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey; the Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers of New Jersey; the County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey; and Partners for Women and Justice, the New Jersey Coalition to End Domestic Violence, Essex County Family Justice Center, New Jersey Crime Victims' Law Center, and Rachel Coalition, which filed a consolidated brief and cited collectively as "Partners" in court documents.

Laura Lasota, an assistant deputy public defender, argued the cause for the defendants. The Public Defender's Office did not return a call for comment.

Claudia Joy Demitro, a deputy attorney general, argued the cause for the state. The Attorney General's Office had no comment.

ACLU-NJ, which argued that the Appellate Division's ruling would "widen[] the net of people incarcerated" and "hamper the efficiency of release hearings," issued this statement: "We're gratified that the Supreme Court recognized that it could protect victims through no-contact orders without creating a system that allowed criminal prosecutions for missing a curfew or showing up late for court. One of the keys to the success of New Jersey's pretrial justice system is its workability—this ruling helps protect that," said Alexander Shalom, director of Supreme Court advocacy for ACLU-NJ.

John McNamara, Jr., chief assistant Morris County prosecutor, argued the cause for the County Prosecutors Association of New Jersey, which closely aligned with the state. CPANJ President Angelo Onofri at the Mercer County Prosecutor's Office. was not immediately available for comment.

Michael Noveck, currently a fellow with the John J. Gibbons Fellowship in Public Interest & Constitutional Law at Newark-based Gibbons, argued the cause for the Partners, which contend that conditions designed to protect victims of domestic violence are a critical part of pretrial release and urged the Supreme Court to reaffirm the holding in Gandhi, which it ultimately did.

"We are grateful to the Court for recognizing that, under its long-standing precedent, the violation of a criminal court's no-contact order can result in a prosecution for criminal contempt," Noveck said late Tuesday. "The Court's decision will thus deter and prevent domestic abusers from harassing, controlling, intimidating, and harming their victims, and it is consistent with the principle that New Jersey law guarantees the survivors of domestic violence with the maximum protection from abuse that the law can provide."

Oleg Nekritin of the Law Offices of Robert DeGroot in Newark submitted a brief on behalf of ACDL-NJ, which closely aligned with the defendants' position. "The ACDL-NJ is pleased with the court's ruling that a contempt charge cannot be applied to a majority of CJRA violations," said Nekritin.

In the first case, defendant Antoine McCray was arrested and charged with second-degree robbery in April 2017. A week later, the trial court released McCray subject to certain nonmonetary conditions, including that he "not commit any offense during the period of release." In August 2017, McCray was charged with various theft offenses for allegedly stealing a wallet and making fraudulent purchases. A grand jury later indicted McCray for fourth-degree contempt, contrary to N.J.S.C. 2C:29-9(a), for violating the trial court's order of pretrial release. The grand jury also returned separate indictments that charged multiple theft offenses. Pursuant to a plea agreement, McCray pleaded guilty to the contempt charge and to four counts of conspiracy to commit credit card fraud.

At sentencing, Superior Court Judge Pedro Jimenez Jr. dismissed the contempt indictment and sentenced McCray to four years in prison on the remaining counts to which he pleaded guilty. In a written opinion, Jimenez traced the history and purpose of the CJRA and noted how the federal Bail Reform Act of 1984 and District of Columbia statute, which the CJRA was modeled after, both provide for contempt prosecutions, but the CJRA does not.

In the second case, defendant Sahaile Gabourel was arrested and charged with possession and distribution of heroin on July 10, 2018. He was released subject to a number of conditions, including a 6 p.m. curfew. Later that month, police officers arrested Gabourel when they spotted him on a street corner just after 8 p.m. The officers also found three Percocet pills in his pocket. Gabourel was charged with fourth-degree contempt, contrary to N.J.S.A. 2C:29-9(a), for disobeying the trial court's release order and violating the curfew condition; and possession of Percocet, contrary to N.J.S.A. 2C:35-10.5(a)(1).

After a hearing, Judge Paul DePascale revoked the order of pretrial release and detained Gabourel, and concluded "the State may not prosecute a noncriminal violation of a term or condition of a pretrial release order by way of contempt." DePascale succinctly recounted the act's legislative history and how it removed "contempt" in the CJRA bill and analogized the situation to a violation of a term of probation, which cannot be prosecuted by contempt. DePascale dismissed the contempt charge against Gabourel.

In reversing both last year, the Appellate Division noted that the CJRA's plain language "does not preclude the State from charging a defendant with contempt" and it was reasonable to conclude that the Legislature believed there was no need to include a provision in the act similar to ones in the federal Bail Reform Act and D.C. Code authorizing a criminal contempt prosecution for a violation of a pretrial release order. The panel also relied in part on Gandhi and concluded the defendants had sufficient notice that they could be charged with contempt and that the Double Jeopardy Clause did not bar McCray's prosecution for criminal contempt.

The Supreme Court, which granted defendants' petitions for certification last year, reversed the panel in both cases in the July 20 opinion.

Similar to the trial judges, Rabner provided a historical perspective of the act—how before the CJRA was enacted in 2014, New Jersey's system of pretrial release relied heavily on monetary bail and that freedom for an innocent-until-proven-guilty person was often based on his ability to scrape enough money together.

"The new law instead relies primarily on pretrial release, accompanied by nonmonetary conditions, 'to reasonably assure' that defendants will appear in court when required, will not endanger 'the safety of any other person or the community,' and 'will not obstruct or attempt to obstruct the criminal justice process,'" said Rabner.

"That calibrated approach is at odds with the State's interpretation — that the Act permits prosecutors to charge defendants with criminal contempt, a fourth-degree crime, for a violation of any release condition, even missing a single court appearance," added Rabner. "That broad-based proposition undermines the CJRA's goals."

This content has been archived. It is available through our partners, LexisNexis® and Bloomberg Law.

To view this content, please continue to their sites.

Not a Lexis Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

Not a Bloomberg Law Subscriber?

Subscribe Now

NOT FOR REPRINT

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.

You Might Like

View All

On the Move and After Hours: Einhorn Barbarito; Gibbons; Greenbaum Rowe; Pro Bono Partnership

4 minute read

Engine Manufacturer Escapes Suit Over NJ Helicopter Crash That Killed Country Music Star

3 minute readLaw Firms Mentioned

Trending Stories

Who Got The Work

J. Brugh Lower of Gibbons has entered an appearance for industrial equipment supplier Devco Corporation in a pending trademark infringement lawsuit. The suit, accusing the defendant of selling knock-off Graco products, was filed Dec. 18 in New Jersey District Court by Rivkin Radler on behalf of Graco Inc. and Graco Minnesota. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Zahid N. Quraishi, is 3:24-cv-11294, Graco Inc. et al v. Devco Corporation.

Who Got The Work

Rebecca Maller-Stein and Kent A. Yalowitz of Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer have entered their appearances for Hanaco Venture Capital and its executives, Lior Prosor and David Frankel, in a pending securities lawsuit. The action, filed on Dec. 24 in New York Southern District Court by Zell, Aron & Co. on behalf of Goldeneye Advisors, accuses the defendants of negligently and fraudulently managing the plaintiff's $1 million investment. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Vernon S. Broderick, is 1:24-cv-09918, Goldeneye Advisors, LLC v. Hanaco Venture Capital, Ltd. et al.

Who Got The Work

Attorneys from A&O Shearman has stepped in as defense counsel for Toronto-Dominion Bank and other defendants in a pending securities class action. The suit, filed Dec. 11 in New York Southern District Court by Bleichmar Fonti & Auld, accuses the defendants of concealing the bank's 'pervasive' deficiencies in regards to its compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act and the quality of its anti-money laundering controls. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Arun Subramanian, is 1:24-cv-09445, Gonzalez v. The Toronto-Dominion Bank et al.

Who Got The Work

Crown Castle International, a Pennsylvania company providing shared communications infrastructure, has turned to Luke D. Wolf of Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani to fend off a pending breach-of-contract lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 25 in Michigan Eastern District Court by Hooper Hathaway PC on behalf of The Town Residences LLC, accuses Crown Castle of failing to transfer approximately $30,000 in utility payments from T-Mobile in breach of a roof-top lease and assignment agreement. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Susan K. Declercq, is 2:24-cv-13131, The Town Residences LLC v. T-Mobile US, Inc. et al.

Who Got The Work

Wilfred P. Coronato and Daniel M. Schwartz of McCarter & English have stepped in as defense counsel to Electrolux Home Products Inc. in a pending product liability lawsuit. The court action, filed Nov. 26 in New York Eastern District Court by Poulos Lopiccolo PC and Nagel Rice LLP on behalf of David Stern, alleges that the defendant's refrigerators’ drawers and shelving repeatedly break and fall apart within months after purchase. The case, assigned to U.S. District Judge Joan M. Azrack, is 2:24-cv-08204, Stern v. Electrolux Home Products, Inc.

Featured Firms

Law Offices of Gary Martin Hays & Associates, P.C.

(470) 294-1674

Law Offices of Mark E. Salomone

(857) 444-6468

Smith & Hassler

(713) 739-1250